THE JOURNAL

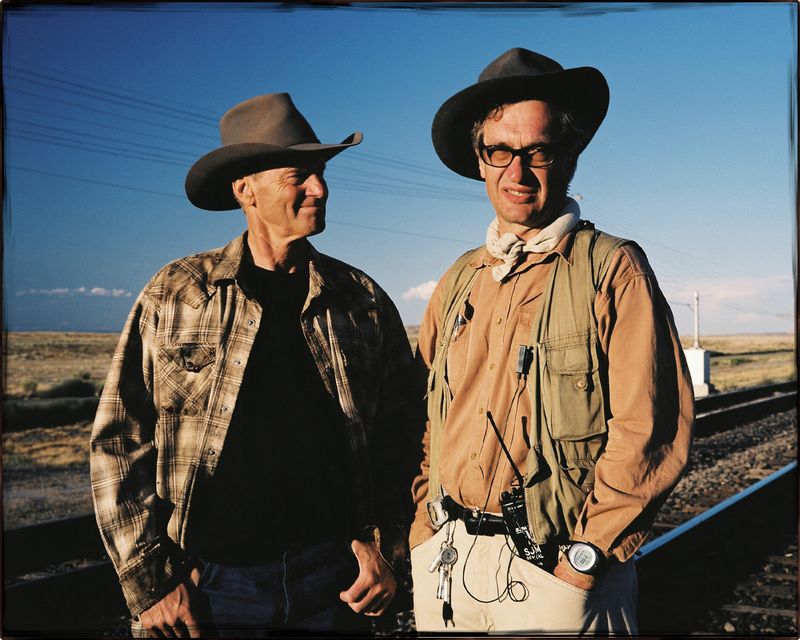

Mr Sam Shepard and Mr Wim Wenders on set of “Don’t Come Knocking”, 2005. Photograph by Sony Pictures Classics/Photofest

“Fashion, I’ll have nothing of it,” says the director Mr Wim Wenders in the introduction to his 1989 documentary Notebook On Cities And Clothes, a portrait of designer Mr Yohji Yamamoto. The Berlin Wall had just come down, and the director felt understandably guilty about making a documentary about something as ostensibly superfluous as style, which he worried was only “a prison, a hall of mirrors in which you could only reflect and imitate yourself”.

What of Wenders’ own style, then? With many of the German directors’ celebrated films, from Wings Of Desire to The American Friend, currently being rereleased and shown in cinemas this summer, here at MR PORTER, we think it’s the perfect time to take a closer look at his wardrobe.

The filmmaker, now aged 75, who helped pioneer the New German Cinema movement with Messrs Rainer Werner Fassbinder and Werner Herzog in the 1960s, has curated a distinctive personal uniform of suspenders and shirts (buttoned to the top without a tie), suiting in linen, tweed and cotton, topped off with his trademark round blue transition spectacles and floppy hair. While at first glance he might seem like a less sharp-edge version of his contemporary Mr David Lynch, or a professor gearing up to teach undergraduates about economic history, his style codes point to something integral about his identity and work.

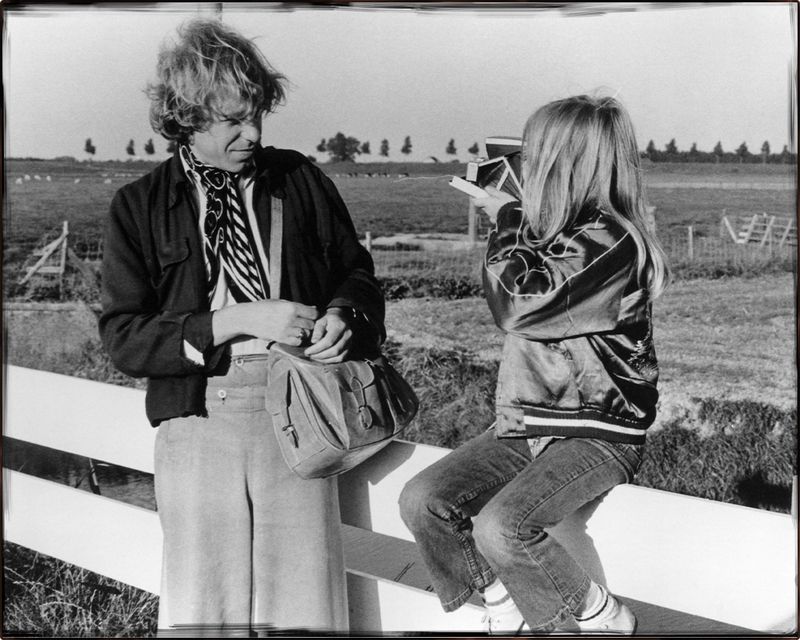

Mr Rüdiger Vogler and Ms Yella Rottländer in “Alice in the Cities”, 1974. Photograph by Bauer International/Imago Images

From the suspenders to the blanket no-tie rule, Wenders’ wardrobe is a not-so-subtle nod to the Hollywood western and the wardrobes of its famous heroes such as Messrs John Wayne or Gary Cooper. Even his more contemporary-looking eyewear carries a cinematic allusion, closely matching those worn by the great director of westerns, Mr John Ford (albeit without the accompanying eyepatch).

Despite not having a drop of red-white-and-blue blood in him, Americana is part of the director’s creative DNA. “Everything I really liked when I grew up was American,” he said in a 2014 interview. Coming of age in a gloomy post-war West Germany, he consumed a colourful, imported diet of Superman comic strips, rock music, cowboy movies as well as literature by Messrs William Faulkner and Mark Twain. The more liberated spirit and expansive horizons of American culture provided welcome relief to an environment, which was “a very narrow space in many senses: it was small to begin with, had lots of borders around, and people were, I felt, quite narrow-minded”.

“More than a prison of endless reflection, for Wenders, finding the right style is a powerful expression of identity and liberation”

It was with his discovery of the road movie that Wenders really found his creative form. “A lot of my films start off with roadmaps instead of scripts,” he wrote in 1988. He used the medium as a backdrop to explore themes such as identity, friendship and masculinity. His 1974 film Alice In The Cities follows the 31-year-old German journalist Philip Winter adrift in the US, literally on the run from a copy deadline (we can relate). Played by the ridiculously good-looking Mr Rüdiger Vogler, he is styled in a wardrobe of cowboy boots, loose bootleg jeans, a suede jacket and neckerchief. His adventure begins when he is entrusted with the care of nine-year-old Alice, riding out his creative and existential crisis with a transatlantic quest, and new paternal purpose, to return the girl to her mother.

Wenders followed up Alice with Kings Of The Road (1978), in which Bruno (also played by Vogler) is a projector repairman who lives a nomadic life driving up and down the Iron Curtain. With a jukebox in the back of his truck, throughout the film, he wears a pair of denim dungarees worn mainly shirtless with a chain, leather jacket and again cowboy boots. His peace is disturbed when the more bourgeois Paul (played by Mr Hans Zischler) crashes his Volkswagen into a nearby river in an attempted suicide. While his suit dries off, Bruno lends him some clothes. Having abandoned his wife and job, he is indeed looking for a new “costume”, a new way of life. The pair feel alienated from the politics of 1970s Germany – its history as well as its future – and the road movie provides a form for the pair to live in the present without getting too deep. In the third part of the film, they steal a pair of sunglasses, which allows them to look at the sky (a space above the Wall) and they drive off in a bike and sidecar, enjoying their moments of freedom.

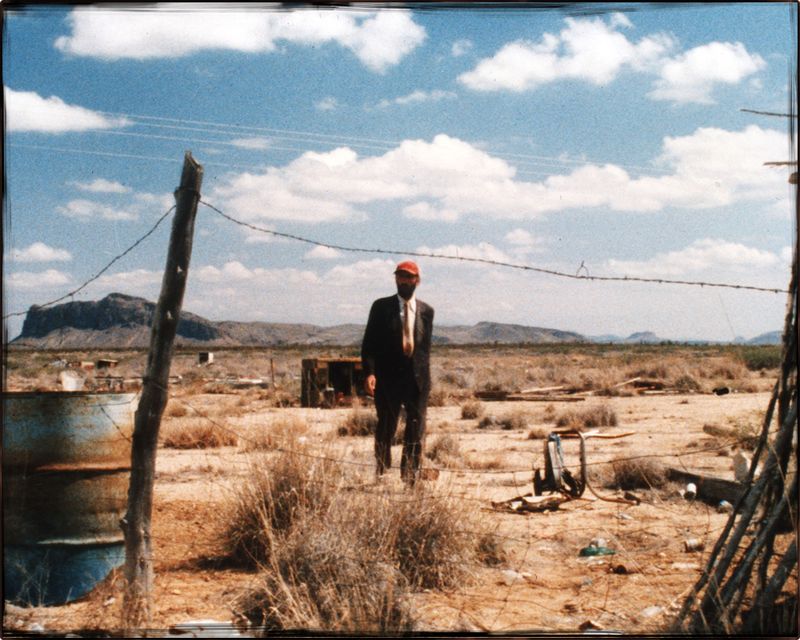

Mr Harry Dean Stanton in “Paris, Texas”, 1984. Photograph by 20th Century Fox/Alamy

The film also marked a kind of homecoming for Wenders. “Unlike other directors from Germany and Austria who have gone to America as an exile, it was never an exile for me,” he explained in a 2014 interview. “It was always some sort of parallel life that I could live somewhere else.”

More than a prison of endless reflection then, for Wenders, finding the right style is a powerful expression of identity and liberation, which equips its wearer with the skin to live an authentic, nobler life. Indeed, a better metaphor than a prison might be that of a shield.

In the documentary with Yamamoto – a designer who himself found success in translating Asian style codes for a European sensibility – Wenders describes the experience of trying on one of his jackets as a profound “experience of identity”. Reminded of his father and his childhood, in it he feels more himself than ever before, “protected like a knight in his armour”.