THE JOURNAL

Dry your eyes, because the musical maverick has returned – with a new film, new tracks and a fresh new style.

It’s hard to imagine not using a vital muscle for seven years. But that’s exactly how Mr Mike Skinner feels about the part of him that wrote the intricate songs for The Streets, the pivotal British act that redefined UK hip-hop in the early 2000s. Mr Skinner’s familiar lad-in-the-pub parlance, then unheard of in the charts, spoke of kebab shops, suburban nightclubs, JD Sports and dancing in Reebok Classics, serving it all up with a sound that was half UK garage, half pirate-radio pop. He was touted as the voice of a generation, but after five albums and the familiar cycle of drink, drugs and breakdowns, he says that the lyrical part of him refused to function.

“Whatever that bit of your brain is that works out what the most important word of the sentence is, and has to make it rhyme, it was really tired,” says Mr Skinner. In the period between 2011 – when he dissolved The Streets – and now, that particular part had been “trained and then not used”, he says. “But when I started to write songs again last year, I had this weird sensation that it was ready to go. All of the things that I taught myself about songwriting were still there. It’s like getting on a bike, and remembering that you’d been Bradley Wiggins.”

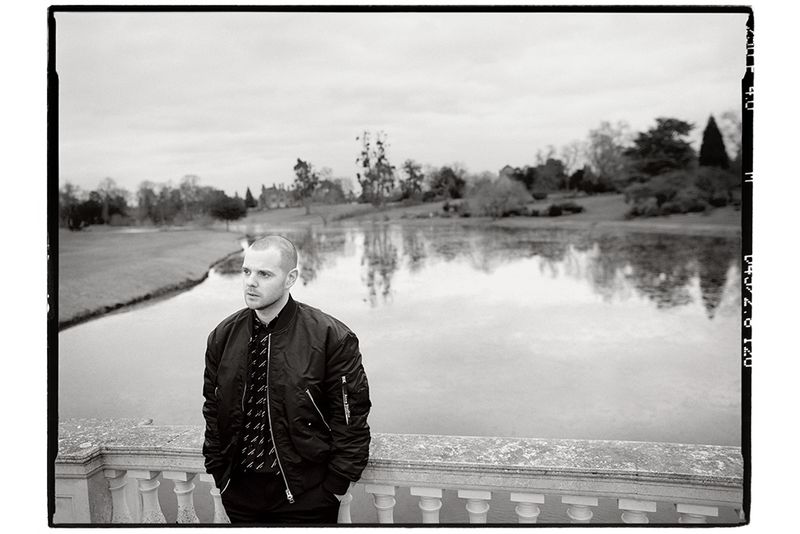

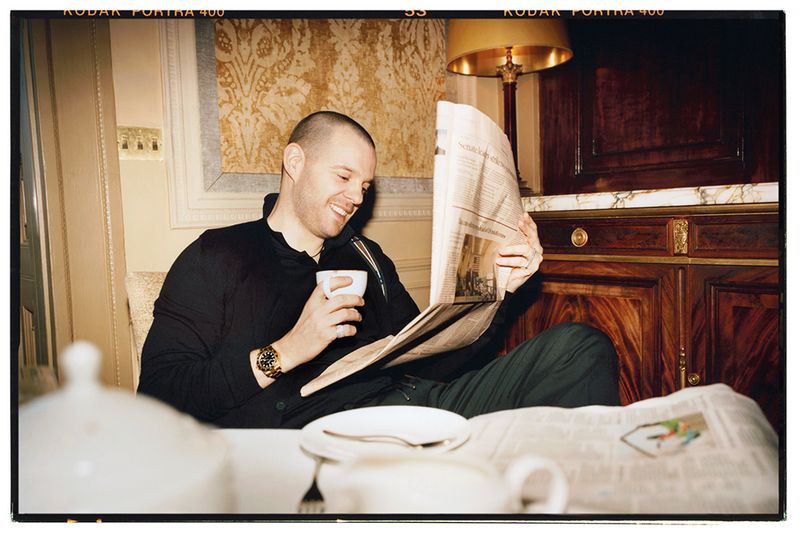

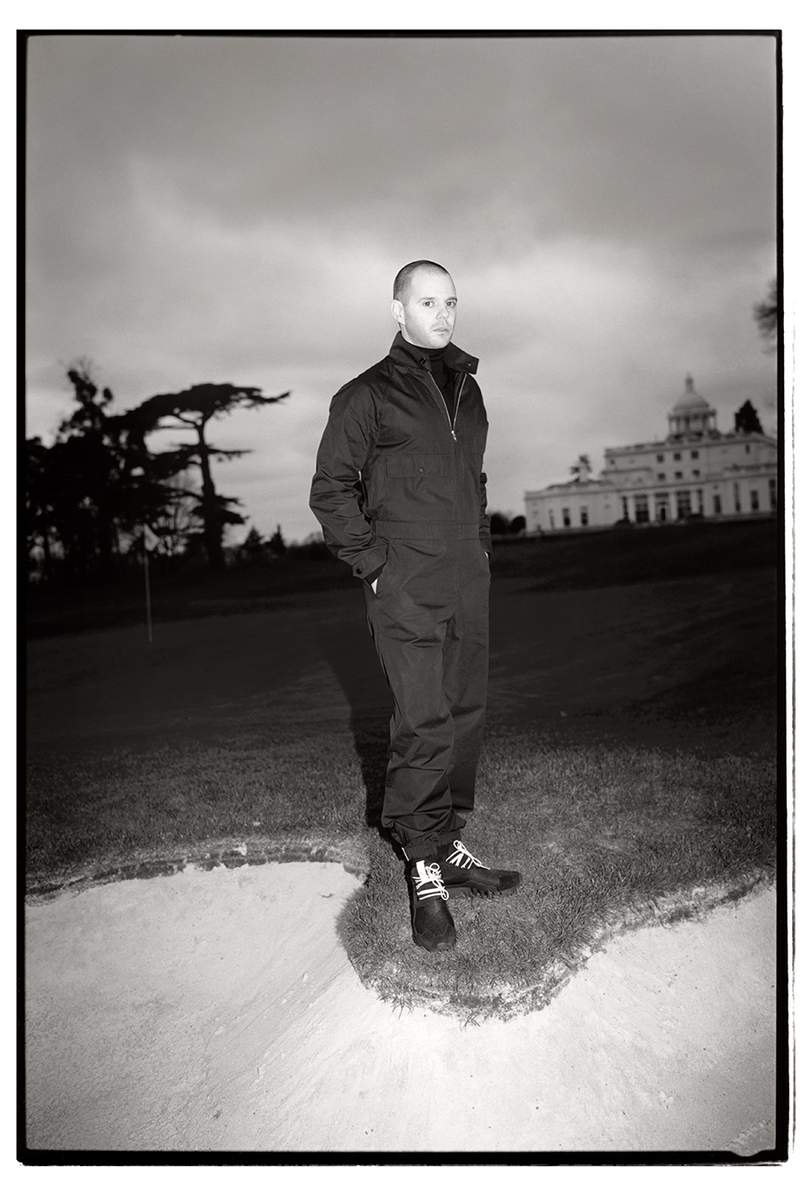

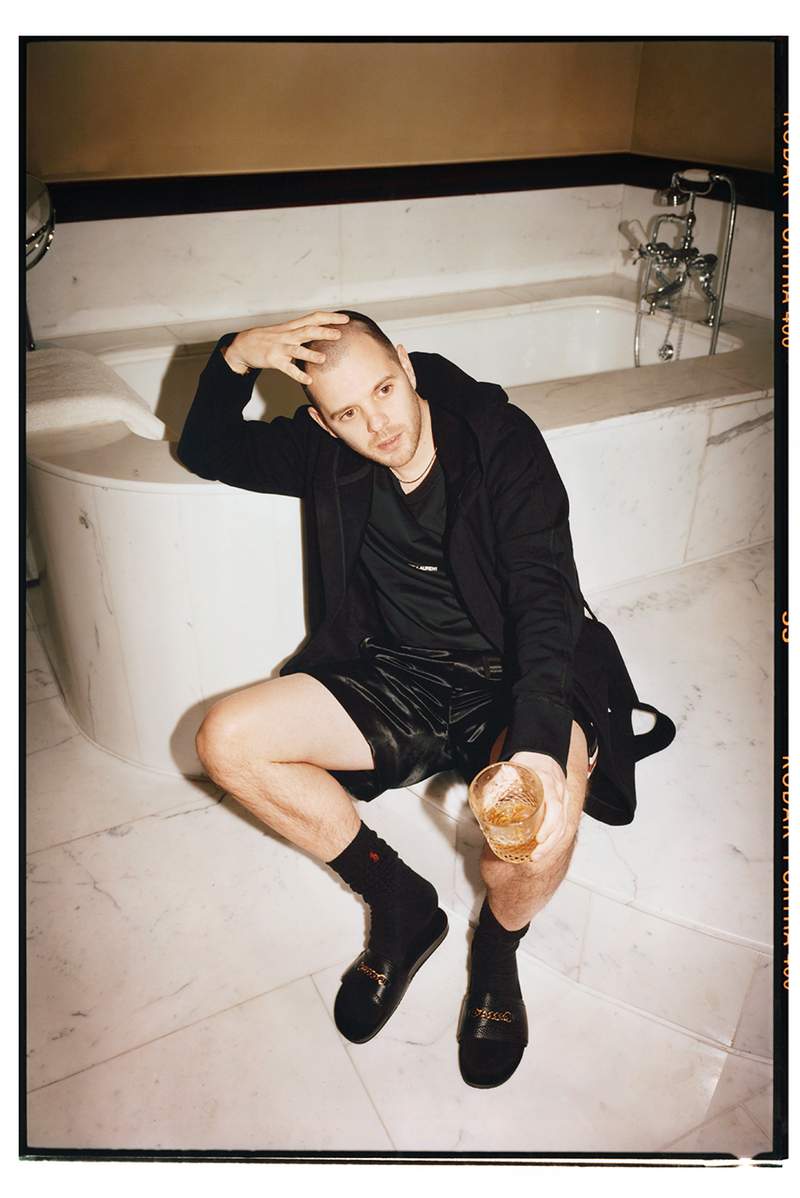

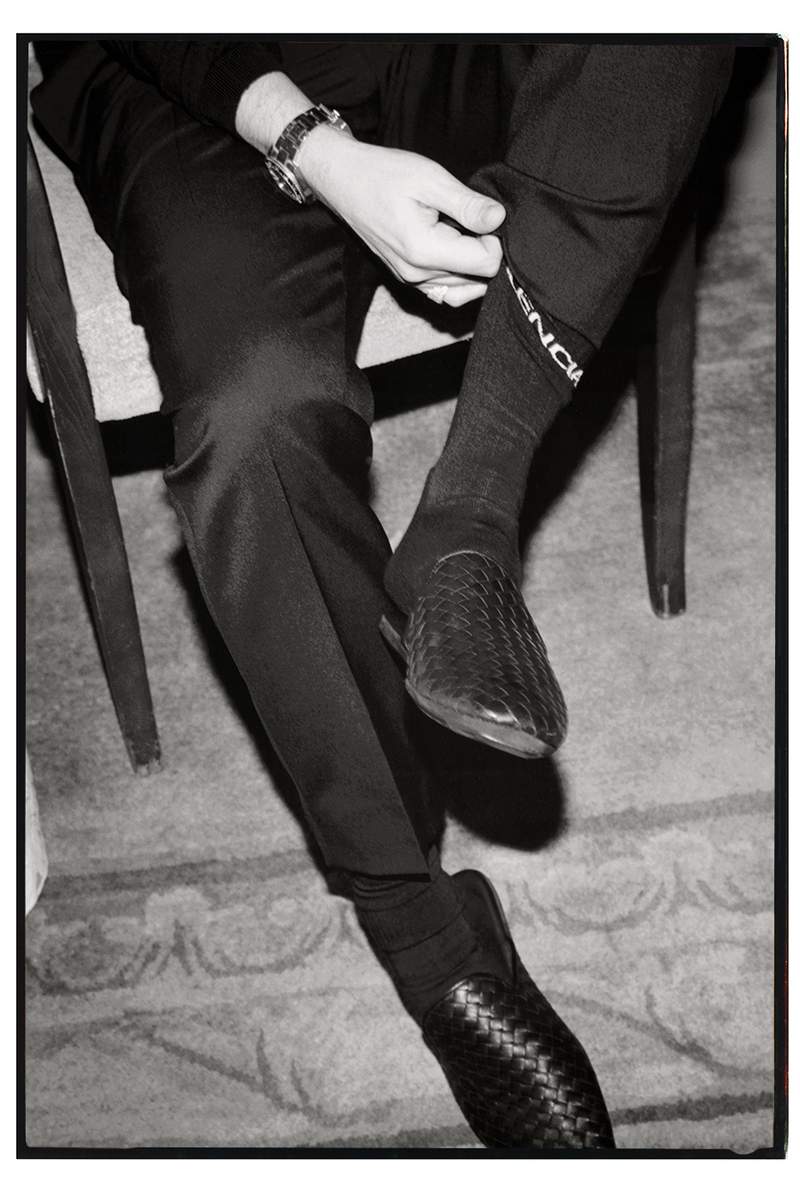

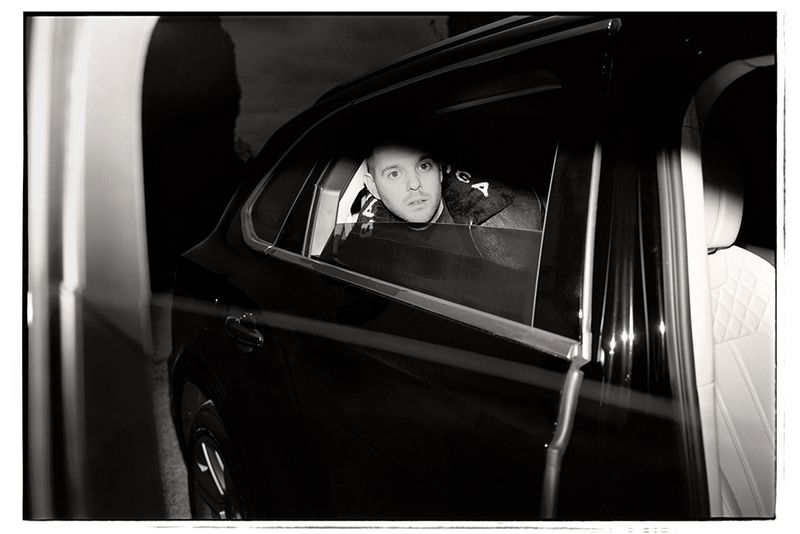

Mr Skinner is back, still with the self-conscious bravado of someone whose storytelling chops have been compared to Messrs Fyodor Dostoevsky and Samuel Pepys. Except now he’s older, a father of two and certainly a little more luxe. After his MR PORTER shoot at Stoke Park hotel in Buckinghamshire, we meet in a nondescript café in a well-heeled enclave of north London, and he is wearing an all-black ensemble of a Fendi tracksuit, gold trim lining the arms, shoes, a flashy watch on one hand and a rhinestone two-finger ring on the other. Sartorially, it’s a few hurdles on from the impish lad-next-door-in-a-polo-shirt look of his early music days, when songs such as “Fit But You Know It” and “Blinded By The Lights” established him as a so-called “lager laureate”. Mr Skinner has always had a tendency towards sportswear, but he dropped the colourful clothing years ago because it was easier to pack and match black clothing on tour. He says that he was never the laddish label lover he was made out to be. “Gucci was my favourite until it got popular,” he says. “I wore one Burberry shirt in the whole [of The] Streets. I never wore Stone Island. No, I did wear Stone Island, in the ‘Dry Your Eyes’ video. But that was all.”

Now, he doesn’t consider himself stylish as such. “I wouldn’t be classed as being very tasteful, I never have,” he says. “I used to wear baby-blue Gap or adidas tracksuits. But when you don’t have taste you can still have a very strong opinion. I had a very clear idea of how I wanted to look.” The uniformity of his current wardrobe, he says, allows for more experimentation. “When you wear black all the time you start to realise that you can get away with a few shapes that you would never have the bottle to do in colour. You can get a bit wild.” He points to his black snakeskin-print slip-ons, smiling. “It’s probably a bit Rick Owens, isn’t it, or ‘health goth’.”

Mr Skinner’s been experimenting with career paths, too. Despite once joking that he’d have “No one likes a polymath” etched onto his gravestone, he’s been doing a fine job of piecing together a portfolio career since he stopped The Streets. He is now an in-demand DJ, often with Manchester musician and promoter Murkage Dave, in a crew-cum-club-night called Tonga that tours the country rupturing student bars with its ravey strain of “party bass music”, and a spin-off podcast, Peak Time. He’s had various music projects along the way, though none have taken off in quite the same way as The Streets. He’s also been directing music videos and short commercials, including one last year starring his old pal Ms Alexa Chung, for her eponymous clothing label. “I have to be creative,” he says at one point, “or I get suicidal or something.”

In just a few months, though, Mr Skinner will be up on a stage singing the songs he wrote 15 years ago, for a comeback tour that sold out in seconds. While a lot of musicians would be gleefully totting up the ticket sales, he seems conflicted. Is he nervous? “My only worry is a much more existential question about what the hell I’m doing,” he says. He fiddles distractedly with a spoon. “But that’s a really long-term thing.” The intricate flow that underscores his songs also comes with its own complications. “I haven’t learned the words yet. Certain songs I’ll never forget. A lot of it I’m going to have to learn again.”

In an interview with NME in 2008, he said the only reason he’d ever reform The Streets was if he was 40 and needed the cash. He turns 40 in November this year. But today Mr Skinner says his reasons for returning (still with manager Mr Ted Mayhem, now without A&R Mr Nick Worthington) aren’t so cynical. “Well, I don’t need the cash, otherwise I’d have done all the festivals, and the offers we got were insane,” he says. The decision to bring back The Streets was more complicated. “There were a few things that Dizzee [Rascal] said when he did the big Red Bull gigs [in 2016, when he played Boy In Da Corner in full]. He said at one point, ‘I know this means a lot to you,’ and it felt like it was his way of saying, ‘But I’ve moved on.’ And I totally get that. I’m gonna celebrate the past.”

He also wanted to find a way to keep pushing things forward. “The reason I finished The Streets was to make a film, and the reason I started The Streets up again was to make a film,” says Mr Skinner. The forthcoming live shows won’t be funding the project per se, but “what they did do was make people pay attention enough that we could have more exciting meetings with people”. He’s been trying to get a film project of some description off the ground for some time. One dormant idea was a hospital thriller that Mr Skinner deemed too pricey to pull off. “I got so angry with myself for not making a film in seven years,” he says. “I started thinking, ‘What do I know about the most? What’s the most interesting thing for me to write about?’ And I came up with DJing.”

The film’s narrative is set in and around London’s nightlife scene and though it has the rather lofty title of The Darker The Shadow, The Brighter The Light, it’s actually “a farce about guys and girls getting into trouble” in a club. He describes it as “a Streets musical, like Casablanca but not as much as La La Land”, which sounds like the elevator pitch he’s been shopping around to producers (he only finished the first draft at Christmas). Unsurprisingly, Mr Skinner approaches writing films like he does lyrics – “my script is very like a Streets album” – although inspiration has come from some unusual places. “The story isn’t clever,” he says. “It’s all in the dialogue, and that’s what I love. What was that teen show where everyone’s a philosopher? Dawson’s Creek – it’s a bit like that. I like [my characters] to say the things that they thought of when they’re walking home from a terrible argument, and thinking, ‘Oh, I should’ve said that.’ Not political correctness, just cleverness. Because stories aren’t reality, they’re an exercise for the mind.”

He is busying himself with making new Streets music, too, which will form the film’s soundtrack. Three songs have so far accompanied the tour news, and he has so much new material for an album that “it’s getting on like Prince, you know, 40 songs”. But despite the grime beat on one of those tracks, “Burn Bridges”, he’s not sure where his music fits anymore. “I’m at a point where I have completely given up on what I think the market is,” he says, somewhere between ambivalence and defeat. “If you’re an artist, you have a filter system, and I think you should be really pure with that. That’s why I work completely alone. I do everything myself. I record, make all the music, even master it myself. I don’t regret things because I have spent so much time on them.”

Mr Skinner is brilliantly unguarded and subtly sardonic throughout our three-hour conversation, though he tends to follow five trains of thought at once, speaking carefully and editing his thoughts until they converge in one direction. He variously compares himself to Sir Elton John (their mutual love of new music), Mr Macaulay Culkin (fame at a young age) and Mr Howard Hughes (megalomania). But, though his DJing has afforded him a new lease of life, he also gives the impression of a weary artist at odds with himself. What stops him from saying yes to huge festival dates, ones that would give him the money to fund his silver-screen dreams?

“It’s very simple,” he says. “I just do what I believe in. I have to carry that. I’m not sitting here thinking I’ve done really well. I have been clinically depressed, on and off, and it has really haunted me, the decisions that I’ve made and the way that I’ve been so self-destructive. But at least I love what I do. You can’t say that I haven’t made smart decisions because what’s smarter than loving what you do? That’s what I have to come back to, really.” So it comes down to integrity? “Or just stupidity. I don’t know. The artists that we remember were all strategic – that Warhol need to do it, that’s attractive to people. It’s not cynical, it’s attractive. And so the people that don’t do that, at best they end up like Van Gogh. But there’s only really one Van Gogh. I haven’t cut my ear off yet.”