THE JOURNAL

The English National Ballet’s man from Havana talks dancers’ diets, occupational hazards and wedding planning.

Mr Yonah Acosta is not on top form. Three months ago, he had surgery on his left knee and then, mid-recovery, he tore his calf muscle. He’s frustrated. Rather like a top-flight footballer, at 27, a principal dancer should be in peak condition, pushing his agility and testing his stamina to its limit.

He’s already done the latter. Towards the end of last year he tore the meniscus in his knee without even noticing. As it became more swollen, he danced through the pain until the Christmas-season runs of Giselle and The Nutcracker came to an end. “I did the whole thing, but actually I was jumping on one leg,” he says. One MRI scan later and he was booked in for immediate surgery.

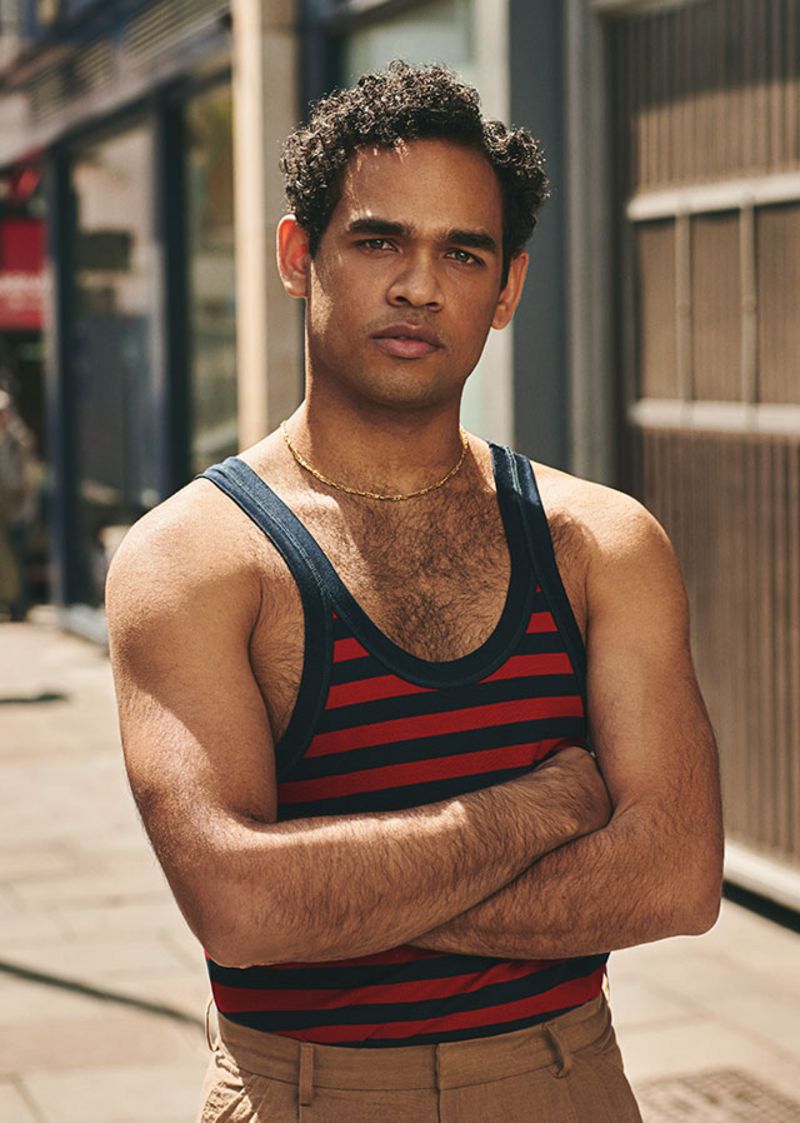

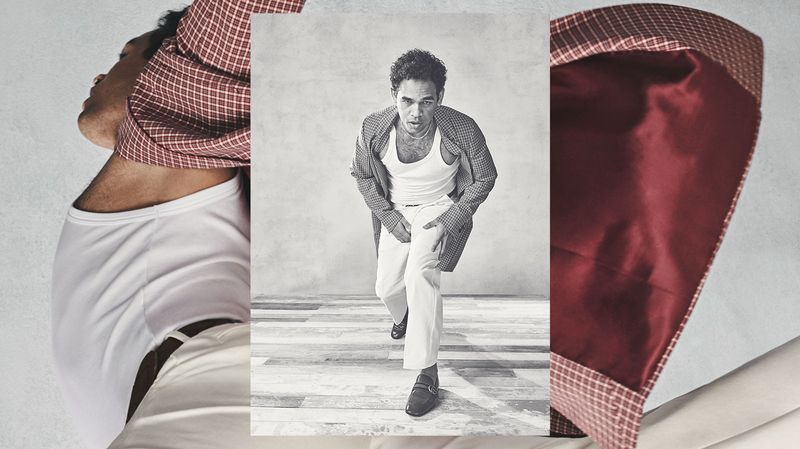

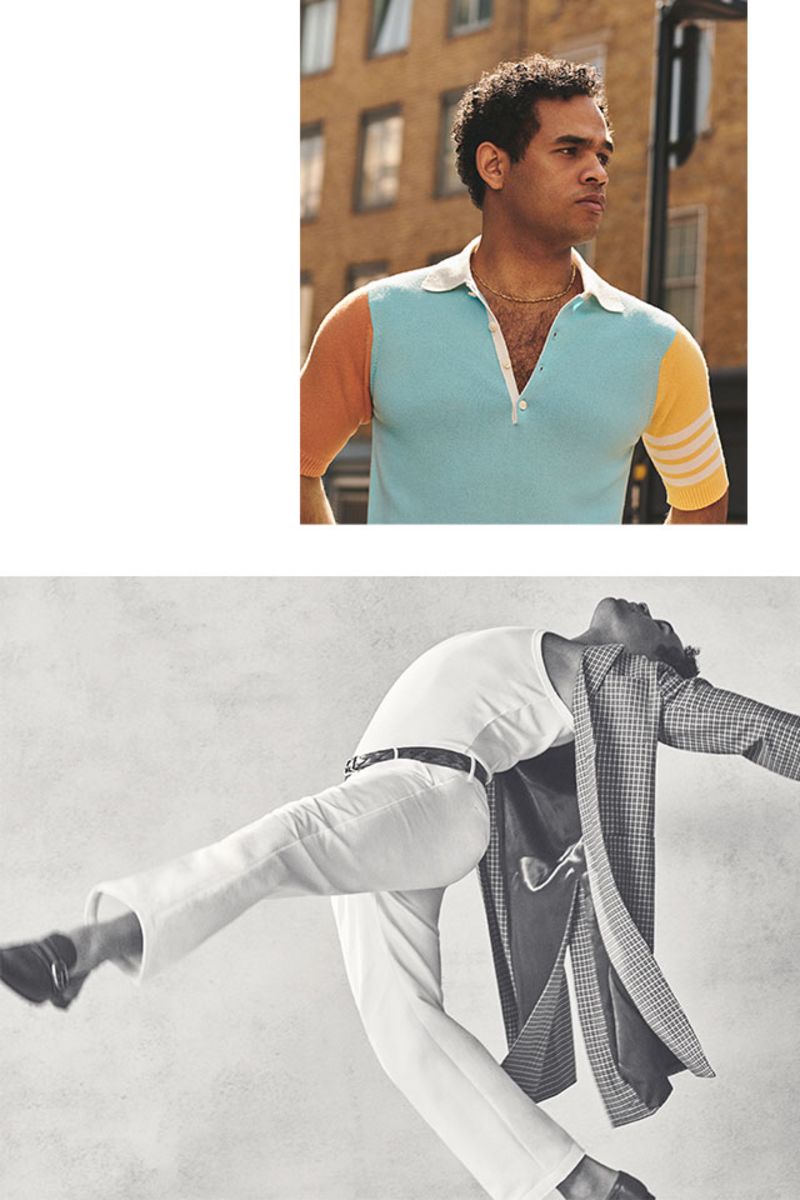

Today, on set, he is itching to be back in the spotlight. Wearing a camp-collar shirt, vintage tee and pleated trousers redolent of the Cuban trend infiltrating the catwalks for SS17, he pliés across Big Sky Studios in King’s Cross, London, with the athleticism of his uncle, Mr Carlos Acosta, whom critics have likened to a modern-day Mr Mikhail Baryshnikov, the Russian ballet star who was considered the greatest male dancer of his generation. With his recovering knee bent at 90 degrees, he launches into a pirouette. His build is different from that of his uncle. He’s shorter and broader – 5ft 8in to Mr Carlos Acosta’s 6ft – but he’s a natural jumper. “My physique and the way my muscles are, it’s for this kind of stuff with jumping and turning,” he says in a thick accent that belies his confident grasp of English.

But he’s not, he admits, in the best shape. “Some of the dancers eat whatever they want and they don’t get fat,” he says. “Unfortunately for me, if I eat too much, I get big, and that’s why I can only eat chicken Caesar salad. I love pasta. But I only eat pasta two hours before the show. It’s quite fast for the body to take in and then gives you energy.”

The life of a principal dancer is full-on. Every day, Mr Acosta drives his BMW one-and-a-half hours from his home in Woking, Surrey, Capital FM blaring out on the radio, to the English National Ballet (ENB) headquarters in South Kensington. The day starts at 10.00am and finishes at 6.30pm. In between rehearsals, there are classes (he says he still struggles with certain positions at the barre) and an in-house personal trainer, Pilates teacher and masseur are always on hand. “I’m not doing any more weights,” he says. “I won’t do weights because I get too big and then it’s not good. It’s not aesthetic for dancers. Most of the time, what I do is lots of stomach, back and legs work.” When the company moves to Canning Town in east London in 2018, he says he will buy a studio flat nearby where he can stay on weeknights.

Mr Acosta moved to London in 2011, having been released by the National Ballet of Cuba’s formidable director Ms Alicia Alonso when the ENB came knocking. He sees himself as one of the lucky ones. Many of his contemporaries who were offered jobs from companies around the world were not so fortunate. “Some of them had really good contracts [offered] and she said, ‘No.’ And then they have to lose the opportunity,” he says. “But, you know, there’s always a second way in Cuba, kind of like an escape.”

Before he arrived in the UK, Mr Acosta recalls being on tour with the National Ballet of Cuba and having to hand over his passport to the company representative as he boarded the coach at every international airport. It was not uncommon for a dancer to disappear, risking losing their rights as Cubans (nationals receive free healthcare) or worse, never being allowed back into the country to visit family and loved ones. He says things are different since a recent shift in foreign policy under President Raúl Castro (younger brother of the late president Mr Fidel Castro).

As an ENB rookie, Mr Acosta won a handful of prestigious rising-star awards and three years ago he was made a principal dancer. Next month, he’s off to Northern Ireland for the first performances of Le Corsaire and Coppélia, in which he plays Franz, an impulsive young cad with a wandering eye, betrothed to his sweetheart but easily distracted. Then the company will travel to Japan in July. “Franz is cheeky,” says Mr Acosta. “If he wants to do something, he just goes and does it. It doesn’t matter what happens after that.” With his easy charisma, you get the feeling he is at home in the light-hearted, comedic space where he can flex his acting muscles.

England, not Cuba, is very much his home now. He lives with his fiancée, fellow ENB principal Ms Laurretta Summerscales. The pair share a house next door to her sister (complete with adjoining garden gate). At home, Mr Acosta relaxes watching Netflix series such as Grimm and Prison Break and, after a hard day’s training, he’ll take Ms Summerscales to their favourite restaurant, Wagamama.

Mr Acosta returns to Cuba only once a year, preferring to fly his parents to the UK. They run a guest house in Nuevo Vedado, a more salubrious district of Havana. He grew up a stone’s throw from the Plaza de la Revolución, which boasts gargantuan memorials to heroes of the 1959 revolution. When he moved to London, one of the first major cultural differences Mr Acosta noticed was how none of his neighbours’ children played in the street. As a child, he remembers endless games of baseball and football. It was his uncle who suggested he try out for the national ballet school, aged 10. (The pair shared the Sadler’s Wells stage four years later and only one other time, in the ENB’s 2014 production of Romeo & Juliet, Mr Yonah Acosta playing right-hand man Mercutio to Mr Carlos Acosta’s Romeo.)

Mr Acosta has only three remaining ambitions: to dance with the Bolshoi, to play Spartacus and to appear as a guest dancer at the Paris Opéra. What about children? “In a couple of years,” he says. He and Ms Summerscales have a wedding to get through first. When he gets back from Japan, 80 guests will descend on Great Fosters in Surrey, a country house hotel with a 1920s outdoor pool and croquet lawn.

Back in Cuba, his friends are embracing the changes that come with economic liberalisation, he says. Wi-Fi hotspots and data bundles have only appeared in the past two years, but they have enabled some families to have face-to-face contact with estranged relatives who sought political asylum in the US decades before. “They feel that they’re going up a level, they’re going a step ahead,” says Mr Acosta. “Well, I feel for them that it’s not a step ahead, it’s just something you guys need to have. They don’t have money to eat, but they have a good phone.”