THE JOURNAL

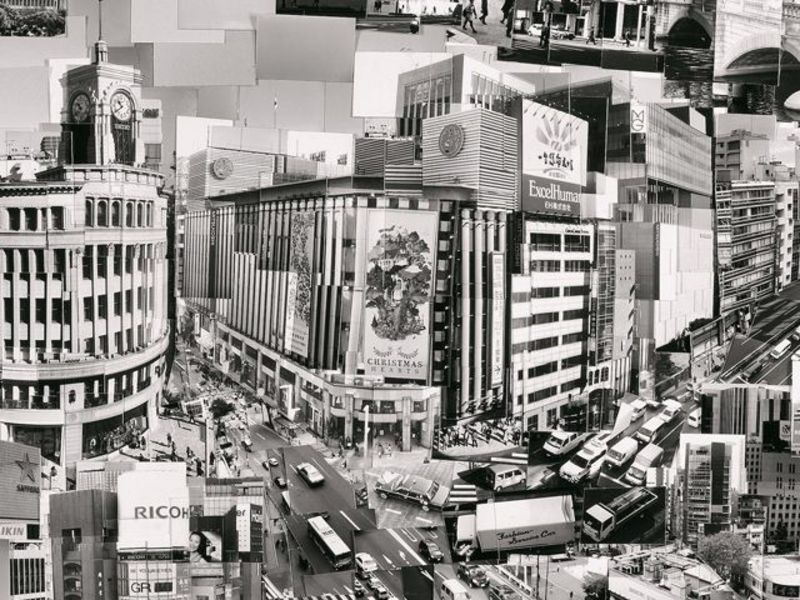

Detail from “Diorama Map Tokyo”, 2014 © Sohei Nishino, Courtesy Michael Hoppen Gallery

The figure of the flâneur – the urban wanderer, casual observer and reporter of street life – has been a key trope in understanding man’s relation to the city since the time of Mr Charles Baudelaire. The French poet saw the flâneur as a dandy, but also as someone keen to experience the city in all its forms.

You could say that Mr Sohei Nishino is Mr Baudelaire’s flâneur reborn with a camera in his hand. Like the Parisian stroller, the young Japanese photographic artist experiences the metropolis and records it, while also remaining detached. He then condenses the experience into unique photographic artworks. Then, when the relationship can go no further, he moves on to the next city. So far there are 17 notches on his proverbial camera strap, and seven of these “urban love affairs” will be on display at London’s Michael Hoppen Gallery, from 30 October to 7 January.

Mr Nishino captures the city beneath him Photo Miho Odaka

So how does he work? “I stay in each city for some weeks,” the 32-year-old artist explains over a chai in a downtown Tokyo café as samba music rumbles in the background. “I take photographs from 40 to 60 places in each city, preferably high buildings. I develop the film in my studio in Tokyo, make prints in the darkroom, cut them up, and start arranging them on a white board.”

The way he does this is not unlike assembling a giant jigsaw puzzle. The photographic fragments are slotted in to create what he calls a “diorama”, a collage that is a rough pictorial map of the city. This is then photographed to create strictly limited editions of LightJet prints that sell for upwards of £30,000.

Unlike most photographic art, his method allows him to emphasise things that made a particular impression on him.

“Personally, I’m not too interested in the touristy places,” he says. “Sometimes I even give them a miss, because I think places off the beaten track can often be more symbolic.”

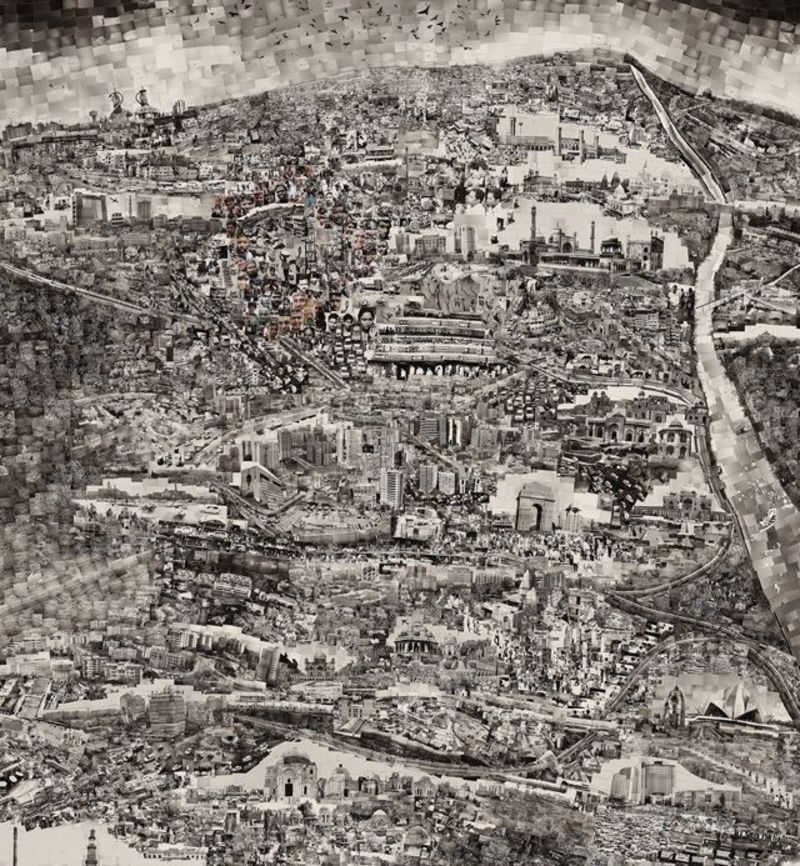

“Diorama Map New Delhi”, 2013 © Sohei Nishino, courtesy Michael Hoppen Gallery

In an age of sleek and accessible digital technology, his artistic process may also seem wilfully laborious or even slightly Luddite. “All the processes are by my hand,” he explains with a hint of pride. “This is the important point for me, to focus by my method.”

This kind of stubborn craftsmanship looks like a quest for authenticity in a world that has become all too glib, technically slick and convenient. It has resonances with the vintage affectations of hipster subculture. So, is he just another young man trying to be old before his time?

“I wasn’t conscious of this aspect when I started,” he replies, “but many people tell me that my art looks like medieval maps. I didn’t do it intentionally, to reach back to an analogue way. Actually, I also like digital technology, so I don’t deny that type of technical progress, but what I do artistically came very naturally. I just prefer each step to take time and to be done by hand.”

The essence of his work is the connection between photography and geography, something that he says developed when, as a student, he followed the most famous Buddhist pilgrimage route in Japan to the 88 temples on the island of Shikoku. The expanded scrapbook he created pointed the way to his later work.

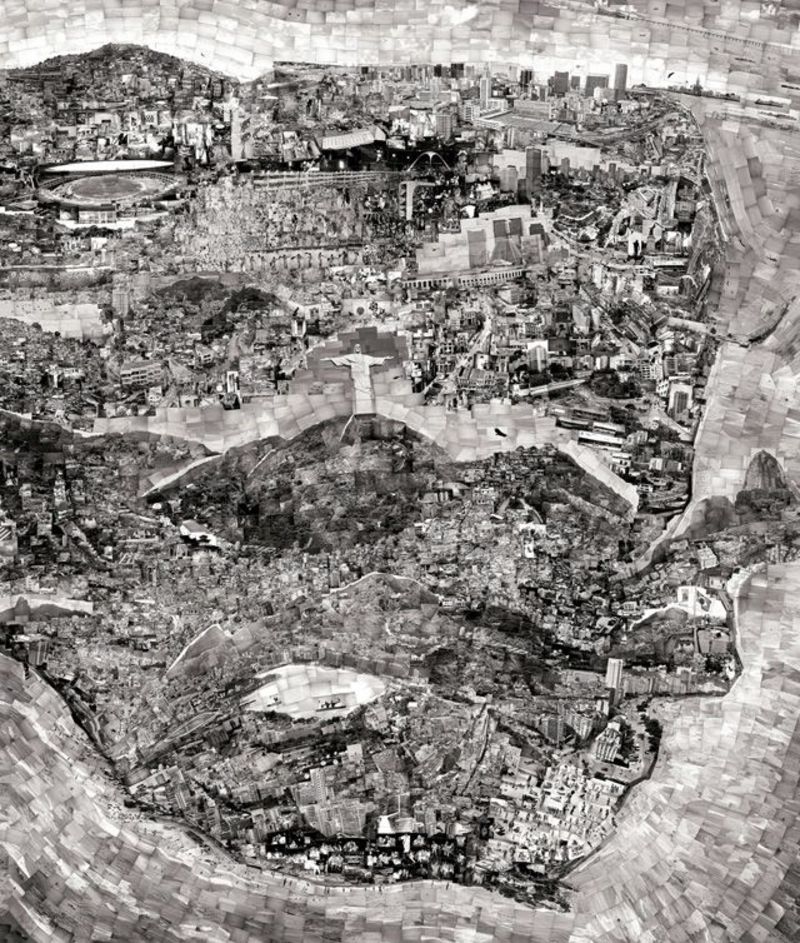

“Diorama Map Rio de Janeiro”, 2011 © Sohei Nishino, courtesy Michael Hoppen Gallery

Some commentators have seen a Cubist influence in the way that Mr Nishino arranges photos taken from different angles on the same plane. This is something he readily admits, citing his time at the Osaka University of Arts. Another key reference point is Mr Italo Calvino’s 1972 novel Invisible Cities, which explores philosophical themes through surreal descriptions of exotic cityscapes narrated by Mr Marco Polo.

“What fascinates me about Calvino’s book is Marco Polo and what he saw or experienced through his journey,” Mr Nishino says, contrasting subjective experience and objective reality. “I think that kind of personal storytelling is much more interesting and important than whether something’s real or not. In this digital age we can reach to the outside world easily with the computer, and we can even look at the other side of the earth through things such as Google Street View, but reality is only important if it is based on one’s experience.”

Mr Nishino claims that his cumulative experiences of each city coalesce to give each one a clear personality.

“Diorama Map Hong Kong”, 2010 © Sohei Nishino, courtesy Michael Hoppen Gallery

“I see each city almost as a portrait, almost as a human being,” he enthuses. “Each time I go inside a city I wonder how I will communicate with it. It’s almost as though the city has its own personality. As I developed my art, I started looking inside the cities more and more. I started to look at the people and how they dressed or what kind of food they ate, and that sort of thing.”

The thing that stands out the most for Mr Nishino, however, is the “signature energy” that makes each city unique. So, how was London?

“It was very strong,” he recalls. “It had a restless energy, and felt tough. But maybe this was partly because on the very first day I had trouble and at the end I got ill.”

Mr Nishino’s next city may also prove a challenge. In December he heads to Johannesburg, which has a reputation for being one of the most dangerous cities on the planet. This could obviously be a problem for an artist who insists on traversing every inch on foot. But, then, art is all about accepting the challenge.