THE JOURNAL

The comic book creators, Messrs Gibbons and Millar

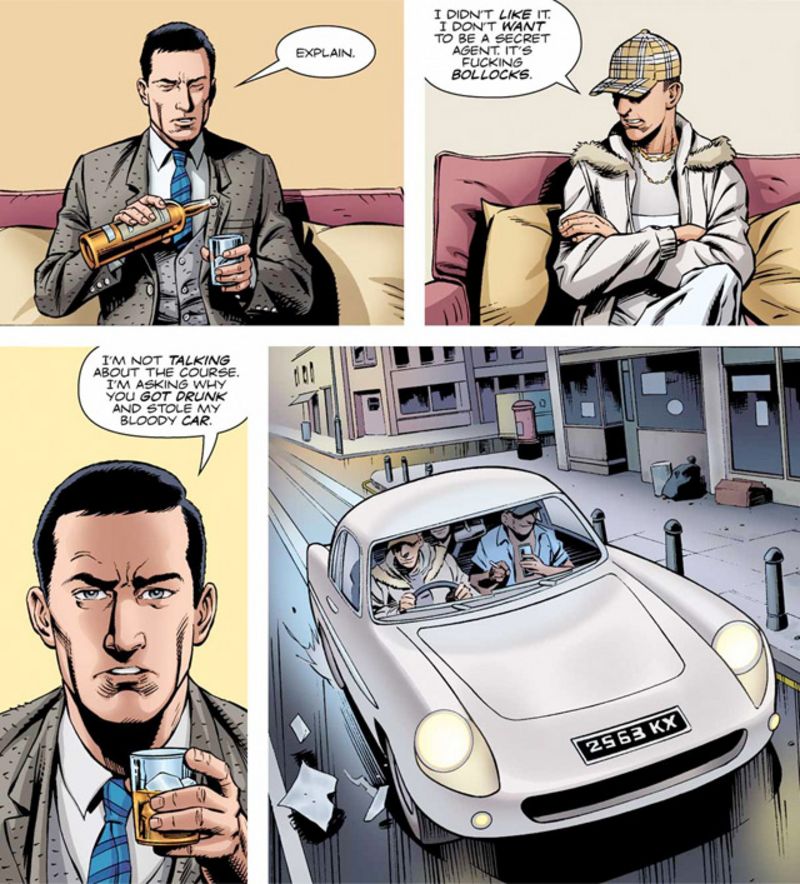

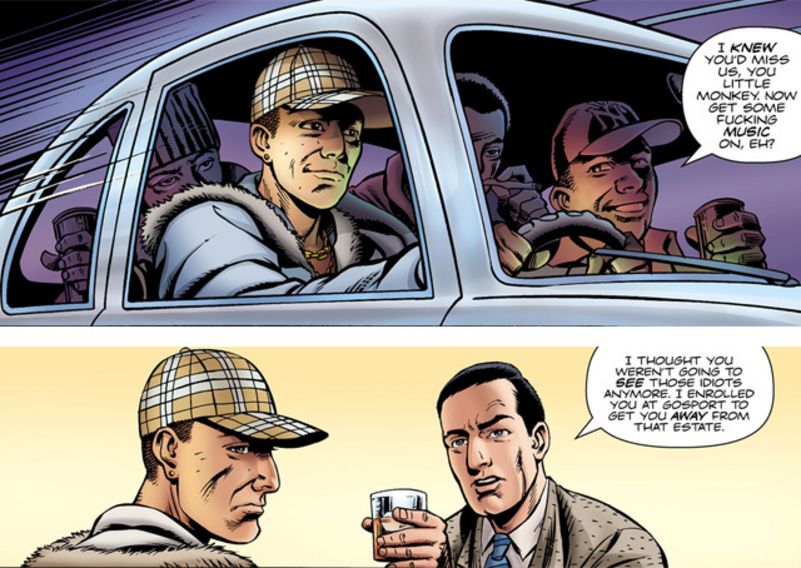

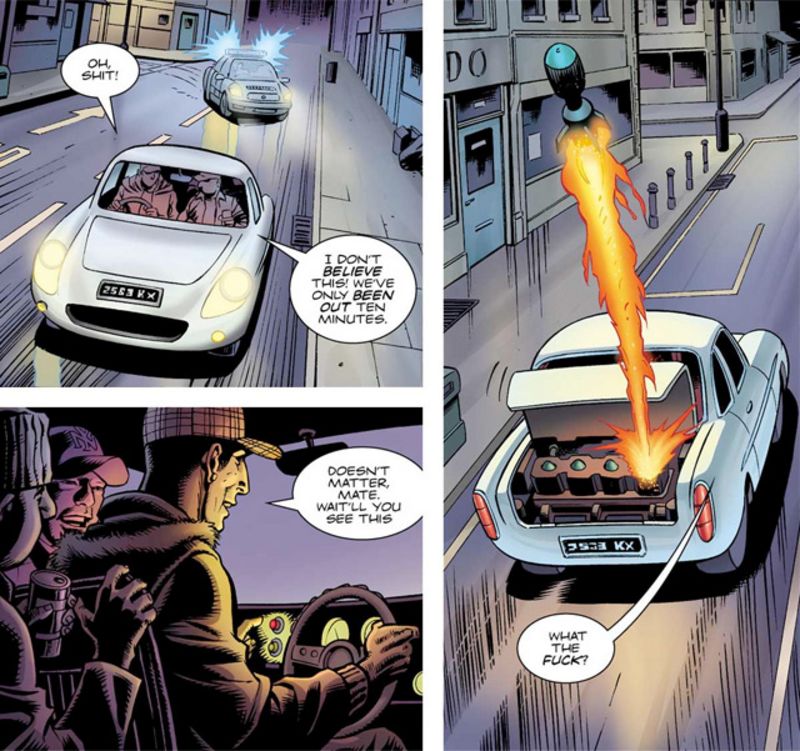

Messrs Dave Gibbons and Mark Millar, the artist and writer behind <i>The Secret Service</i> series, reveal the origin of their spy saga.

One afternoon in 2008, two men, one a Glaswegian comic-book writer named Mr Mark Millar, the other a London film director named Mr Matthew Vaughn, took a break from the production of the movie Kick-Ass. They walked to a quiet pub. Inside, the landlord was drying glasses with a towel and staring into space. The men each ordered a beer, and carried their drinks to a table. As they sat down, they started to chat about Casino Royale, the James Bond film that introduced Mr Daniel Craig to the franchise.

“We were talking about how it was weird that [the film-makers] hadn’t shown the origin of James Bond, which was what we were expecting,” remembers Mr Millar. The two were thinking _Casino Royale _would be a reboot of the franchise, similar to what Mr Christopher Nolan had done with Batman Begins. The results of that conversation were, firstly, The Secret Service, a comic series written by Mr Millar, co-plotted by Mr Vaughn and drawn by Mr Dave Gibbons (first published in 2012), and then Kingsman, a new movie directed by Mr Vaughn and based on the comic series.

Once Mr Millar started work on _The Secret Service, _creative choices quickly followed: should the character be British like Bond, or American like Bruce Wayne? “I thought about making it American, to give it a more international appeal, but that felt wrong. The spy is the British version of the superhero. The superhero is essentially a power fantasy for Americans – dress up in the flag and go out and tell people what to do, but in Britain it’s dress really well, have a drink, a smoke and sleep with someone.”

Mr Millar goes on to explain that the history of the James Bond story also influenced the plot of The Secret Service. “Sean Connery was a rough-and-ready milkman from Edinburgh, and Ian Fleming was aghast that he’d been cast as James Bond, because he wanted somebody such as Cary Grant. So, to put him at ease the director said, ‘I’ll take him to my club, I’ll teach him to be a gentleman.’ It was like Pygmalion for boys – he took him to his tailor, bought him his first suit and turned him into James Bond.”

The decision to dress The Secret Service’s central character Galahad (played by Mr Colin Firth in the Kingsman film) in a suit is also inspired by Bond, according to Mr Millar. “Nobody else dresses formally and is respected for it,” he says. “Bond made conservative dressing extremely cool, in a way that probably no other fictional character has ever done. He was originally dressed like a Conservative MP but he was still thought of as cool at a time when Mick Jagger was cool.”

It’s an approach to style that Mr Gibbons, the artist who drew The Secret Service, and a mod as a young man, understands well. “I was obsessed with fashion,” he remembers. “I used to go up to London when I was a schoolboy just to get my hair cut. It had to be just the right shirt, the right scooter and the right Levi’s. It’s great to look back to the mod movement, it’s still cool and it still looks good.”

Mr Gibbons is a legend in the world of graphic novels, having worked alongside the writer Mr Alan Moore on the famous mid-1980s series Watchmen. He explains his first contact with Mr Millar: “When he just left school he wrote me a letter saying that after the success of Watchmen I should do a story with him. I had no memory of this, but as the years went on I became aware of his work, I followed The Ultimates, which he did for Marvel, and later he pitched me the idea of doing a spy story.”

Having decided to collaborate on The Secret Service, how did he set about turning the story into a comic? “Drawing a comic strip is bringing dead words alive. The way to do it is to read it thoroughly, so you have a movie in your head of what’s supposed to be happening, and then you pin down the moments you’ve got to draw.” It’s at this point in the process that Mr Gibbons reaches for his varied tools, which range from watercolour brushes and Indian ink, to digital graphic tablets.

However, even the leap from words to a comic strip is simpler than the jump from a comic series to a movie, and going on set can be discombobulating for the man who created the source material. Mr Gibbons remembers, “In Watchmen, Nite Owl has an Owlship, and they built a full-size model of that [for the movie]. I found myself in this machine that had originally existed as a sketch in my head.”

One of the things that jumps out from The Secret Service is a strong message of Nietzschean self-determination, in the form of the choices that the character Eggsy makes to escape his background. This is something Mr Millar passionately believes in. “Geography doesn’t really mean anything,” he says. “Where you’re born doesn’t mark who you’re going to be. It sounds almost callous to say this but everything really is a choice. I grew up on a council estate in one of the poorest parts of Scotland. Take one of my best friends from school. He had a single mother raising him in the housing estate we grew up in, and he now has a chauffeur and a $20m jet. By working hard you can transform everything around you.” The writer takes a similarly uncompromising approach to dressing, saying, “If you look like crap you’ll be treated like crap.”

Authors are often left unsatisfied by film adaptations of their work, but Mr Millar is an exception, even though the Kingsman movie is quite different from The Secret Service comic series. “You only know how good Matthew [Vaughn] is when you see him at work, his attention to detail is just incredible. Every single moment in the movie really sings. It’s very unusual for a director to make five great movies in a row, people can have a misfire – Spielberg had 1941 by his third movie – but Matthew’s made five great films and this is his best one.” And, crucially, the first to confirm our long-held suspicion that there’s no contradiction between the hyper-masculinity of secret agents and an appreciation of fine English tailoring.

Illustrations by Mr Dave Gibbons