THE JOURNAL

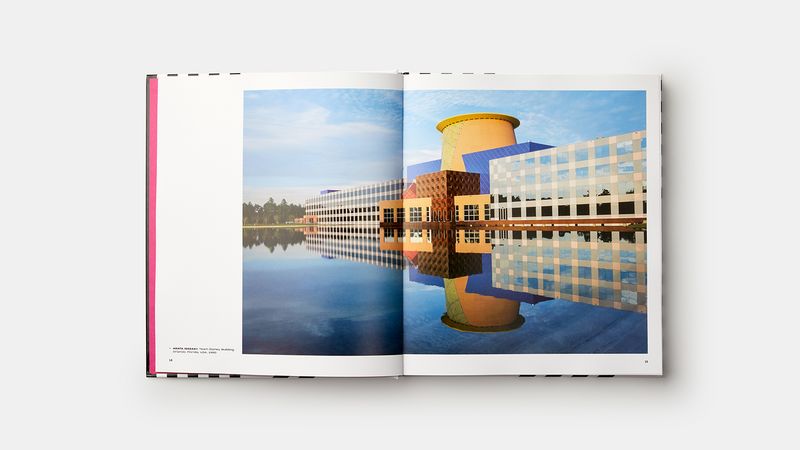

Mr Arata Isozaki, Team Disney Building, Orlando, Florida, US, 1990. Photograph by Mr Peter Aaron/OTTO Archive, courtesy of Phaidon

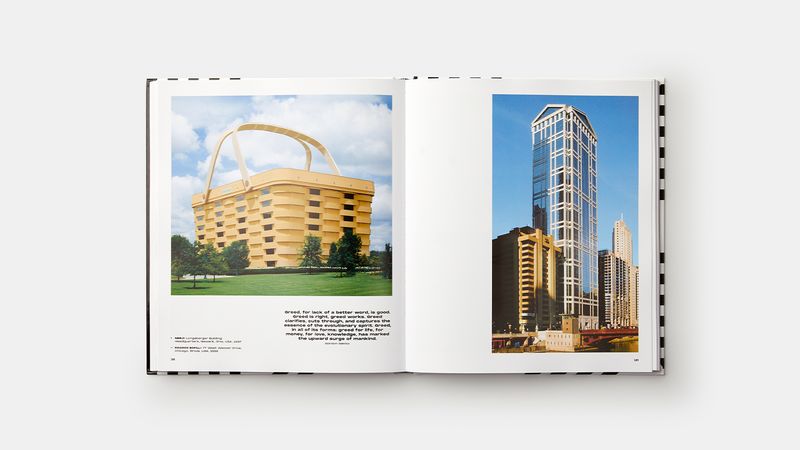

“Just look at the buildings that have gone up in, say, London over recent years,” says architectural historian Mr Owen Hopkins. “They’re cheap, generic rubbish, put up to make money, not with a view to the contribution that architecture can make to a city. It’s all play-it-safe architecture. Where are the big, bold expressions? Where’s the interest, the meaning, the fun in buildings?” Where, in short, are the postmodern ones? Mr Hopkins may well have a beef with the state of contemporary architecture – he’s the author of new tome Less Is A Bore: Postmodern Architecture and senior curator of exhibitions and education at Sir John Soane’s Museum in London – but it takes only a brief survey of postmodernism’s greatest hits to see that he has a point. Take a look at NBBJ’s Longaberger building in Newark, Ohio, which resembles a wicker picnic basket, or Mr Kengo Kuma’s M2 building in Tokyo, with its single gigantic Ionic column, or the spiky ziggurat of Mr Philip Johnson and Mr John Burgee’s Bank of America Center, in Houston, Texas. With postmodernism there’s a cacophony of colour, shape, surface, lightness, irony and tongue-in-cheek historical references, a willingness to embrace complexity and uncertainty, rather than, as with modernism before it, a search for some final, certain word on how buildings should look and, by turns, how we should live.

From left: NBBJ, Longaberger Building Headquarters, Newark, Ohio, US, 1997. Photograph by Mr Andre Jenny/Alamy, courtesy of Phaidon. Mr Ricardo Bofill, 77 West Wacker Drive, Chicago, Illinois, US, 1992. Photograph by Mr Marshall Gerometta, CTBUH, courtesy of Phaidon

Postmodernist buildings come not in greys and silvers, but in vibrant hues, maybe several at a time, some to highlight details, some in vast plains of uplifting brights. Architectural flourishes more commonly found in old town squares – clock towers, belvederes, columns and cornices, roof cresting and other decoration – reappear self-consciously out of place on new buildings. There’s a playfulness with form, less of the 21st-century skyscraper’s streamlining, more Lego buildings with shapes that jut out or stack up. The postmodern building can look as though different elements were decided on by different architects and are all the more entertaining for it. They’re disruptive.

Perhaps that’s why postmodernism is being reappraised. It is, as Mr Hopkins argues, the perfect style for now. “Postmodernism came up in times of flux and transition, in times of a shift from one political or economic order to another, and we’re going through that shift again now,” he says.

It’s a style that echoes the complexity and contradiction of this digital era, that chimes with a more visual culture, too. “Postmodernism became the look of the 1980s and associated with rampant consumerism,” says Mr Hopkins. “It’s been tainted by that association. It’s been unfairly maligned. What’s ultimately refreshing about postmodern architecture is that it’s interested in mixing aesthetics. It isn’t hung up on some moral agenda [as modernism was], the idea that architecture must improve the world. It’s happy to be populist, to mix high and low.”

Sir Terry Farrell and Partners, SIS Building, London, UK, 1994. Photograph by Mr Keith Erskine/Alamy, courtesy of Phaidon

And in doing so, to have some character, like it or not. Postmodernist architects of its boom period from the late 1970s to the mid 1990s recognised that most buildings are not for ever, so why not allow them to bring some joie de vivre to the urban landscape while they’re standing? Perhaps ironically, 17 postmodern buildings were added to the UK’s listed building register in 2018, among them the Judge Business School in Cambridge, with its multi-coloured criss-crossing elevated walkways that link curvaceous walls, and the Gough Building at Bryanston School in Dorset, which has its outsized porthole windows mounted atop what look like giant stone corkscrews.

Mr Robert Venturi, one of the grand masters of postmodernist architecture, argued that, far from being a product of the flash, brash 1980s, a kind of postmodern thinking has popped up throughout architectural history. A similar playfulness is seen in baroque architecture and in the buildings of Messrs Nicholas Hawksmoor, John Nash, Antoni Gaudí and Louis Kahn. Unfortunately, Mr Venturi’s argument didn’t prevent a backlash – postmodernism just lacked the high seriousness demanded of supposedly “proper” architecture.

But that was the point. Humour is easier to live with. Eclecticism is freeing. Perhaps that’s why it’s creeping back, not just in a renewed appreciation for postmodernism’s classic examples, but in buildings that have been constructed over recent years, such as WAM Architecten’s Inntel Hotel in Amsterdam, which looks like a number of traditional Dutch houses stacked on top of each other, or FAT and Mr Grayson Perry’s A House For Essex and even, according to Mr Hopkins, among the coming generation of architects. So expect a full-blown postmodernist revival in about 20 years’ time.

“Go around architectural school degree shows and you see all sorts of echoes of postmodernism now from young architects who weren’t indoctrinated against it – fresh ideas of how colour and ornamentation and other postmodern architectural tactics might be used,” says Mr Hopkins. “Some of it is just fashion, but much of it is more fundamental. And I’m all in favour of it. It’s time our cities saw more competing architectural styles, rather than the mono culture we’ve had.”

Image courtesy of Phaidon