THE JOURNAL

Mr Francesco Moser, 1986. Photograph by Sirotti

Eight cyclists who made the Giro d’Italia an unmissable sporting event .

After completing 3,615.4km, 13 mountain stages and coming out on top, being decked out in the colour of the season might be little more than an added bonus for the winner of this year’s Giro d’Italia. It is, though, fitting that pink finds itself so warmly received at the very moment this great tour of perhaps the greatest cycling nation begins its 100th edition.

The inaugural Giro rolled out of Milan on 13 May 1909 (the competition was suspended during the two world wars) as something of a PR stunt for sports newspaper La Gazzetta Dello Sport. Italy had been a unified state for less than 50 years and beyond the cobbled city streets there were only dirt roads. But La Gazzetta’s editor had seen the success the French title L’Auto had achieved with its Tour de France association and, getting the jump on a rival publication, persuaded the owner to back an Italian race. The elusive maglia rosa (pink jersey) for the general classification leader was introduced in 1931 as a nod to the pink paper that the newspaper was and still is printed on.

The colour wasn’t to everyone’s liking. Fascist dictator Mr Benito Mussolini was more than happy to exploit the race’s propaganda potential, but he branded the winner’s jersey effeminate. But it’s no accident that the signature shade of Paul Smith and Rapha – two very different brands that both in their own way draw on cycling’s rich heritage – is pink, not yellow. The Giro is “in the eyes of many fans and a lot of riders… the most beautiful – and difficult – grand tour”, writes Mr Colin O’Brien in Giro d’Italia: The Story Of The World’s Most Beautiful Bike Race. “Because unlike the Tour [de France], which is often formulaic, and dominated by the strongest, richest teams, the Giro is unpredictable and capricious… It’s a race for purists.”

The word “style” in cycling circles tends to refer to the way a man rides, not how he dresses. “You don’t win a Giro by riding conservatively,” says Mr O’Brien. “You have to grab it by the scruff of the neck.” Here are eight men who did just that.

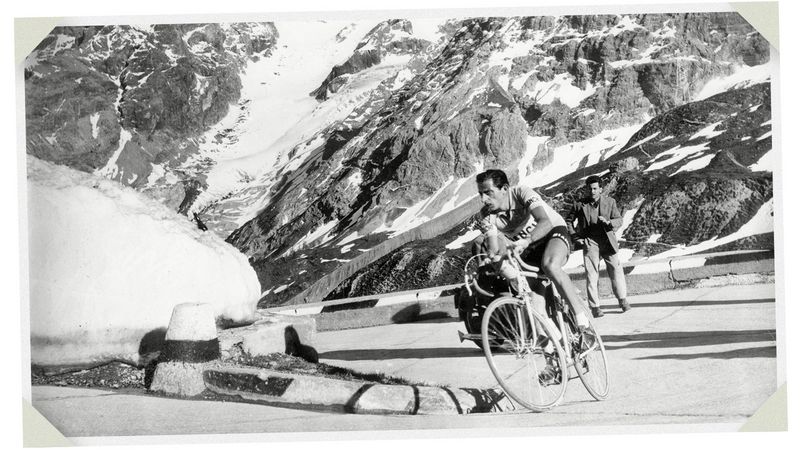

Mr Fausto Coppi

Mr Fausto Coppi, climbing Passo dello Stelvio, 1953. Photograph by Olycom SPA/REX Shutterstock

The dominant cyclist of the mid 20th century, Mr Fausto Coppi is one of just three riders to have won the Giro five times, which is even more of a feat when you consider that WWII put his career on hold at its peak. His life was also tragically brief – he contracted malaria while a guest of the president of Burkina Faso and died on the second day of 1960, aged just 40 – but more than anyone else, he came to define the economic miracle of that era. He was “the living embodiment of post-war Italy: secular, ambitious, elegant and effortlessly cool in finely tailored suits and sunglasses”, says Mr O’Brien. “That mid-century, La Dolce Vita style. And he was one of the first to have that Hollywood look.”

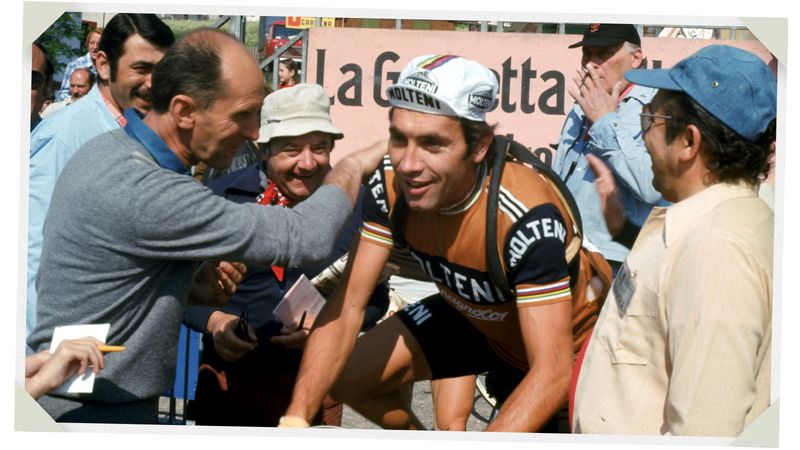

Mr Eddy Merckx

Mr Eddy Merckx, Vigo di Fassa, 1976. Photograph by Sirotti

“A rouleur is an all-rounder who rides well on most types of terrain. Rarely the best at any one discipline, but annoyingly strong,” write the mysterious collective known as the Velominati in The Hardmen: Legends Of The Cycling Gods. “Eddy Merckx, the Prophet, the greatest cyclist of all time… was the consummate rouleur.” Mr Merckx was the most recent to join the elite band of five-time Giro winners (back in 1974). While there’s no doubt that with his Mr Elvis Presley haircut and long sideburns, he exuded sartorial nouse, on the bike, he has been described as a force of nature – “the strongest wind that there is”, according to Italian journalist Mr Gianni Mura. There were those who argued that he was too good, muscling all sense of competition out of the Giro. Mr Merckx’s response: “Whoever doesn’t give his best is the one who kills cycling.”

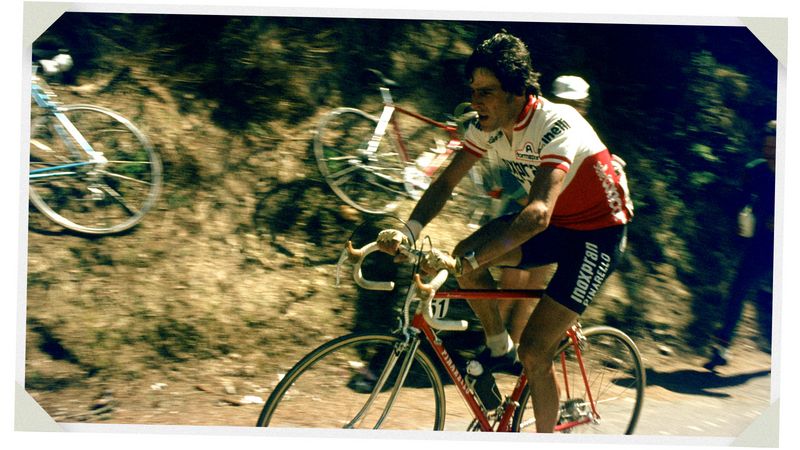

Mr Francesco Moser

Mr Francesco Moser, Merano, 1986. Photograph by Sirotti

Known as Lo Sceriffo (the sheriff), Mr Francesco Moser was “equally deadly on the track, road and cobbles”, say the Velominati. “He was one with his bike. Bent low at the hips, with a flat back and a powerful, smooth stroke.” As well as his fluid riding style, the 1984 general classification winner was noted for his “I will dominate you and look fucking fantastic doing it” attitude (as the Velominati rather nattily put it). He came into the sport at a relatively late age, working on his family farm until he was 18. But he more than made up for lost time, winning 273 races, taking three Paris-Roubaix titles – the 260km race characterised by its cobblestones, earning it the nickname The Hell of the North – and setting the record for distance cycled in an hour (49.431km). Not one to forget a grudge, Mr Moser maintained a fierce rivalry with his competitor Mr Giuseppe Saronni long after his professional career was over. Well into his sixties, he still complained about Mr Saronni’s boast that he could beat Mr Moser while wearing slippers. “I didn’t say slippers,” Mr Saronni clarified in 2015. “I said tennis shoes.”

Mr Marco Pantani

Mr Marco Pantani, Foggia, Vasto, 1998. Photograph by Mr Cor Vos

The first Italian to do the Giro-Tour double since Mr Coppi, Mr Marco Pantani has been likened to an artist rather than an athlete. He had a presence that transcended the garish kits of his late-1990s peak. Sartorially, his taste for wacky accessories and flashy jewellery didn’t help, although it did serve a purpose. “When he launched an attack, he’d throw off his bandana and sunglasses to say ‘I’m going for it,’” says Mr O’Brien. Some spectators did even better out of his castoffs. “His grandfather told him to lose the diamond stud because it weighed him down, so he’d toss it into the bushes.” As Mr Pantani himself put it, “When I attack, I try to psychologically destroy my rivals, who never know how far I can go.” Sadly, we never found out how far he could go. Leading the 1999 Giro, he was expelled from the race with just one stage to go after failing a drug test. For the remainder of his career, he was plagued by allegations of doping. He died in 2004, aged just 34, of acute cocaine poisoning. “To see Marco Pantani at his best was to believe in magic,” says Mr O’Brien.

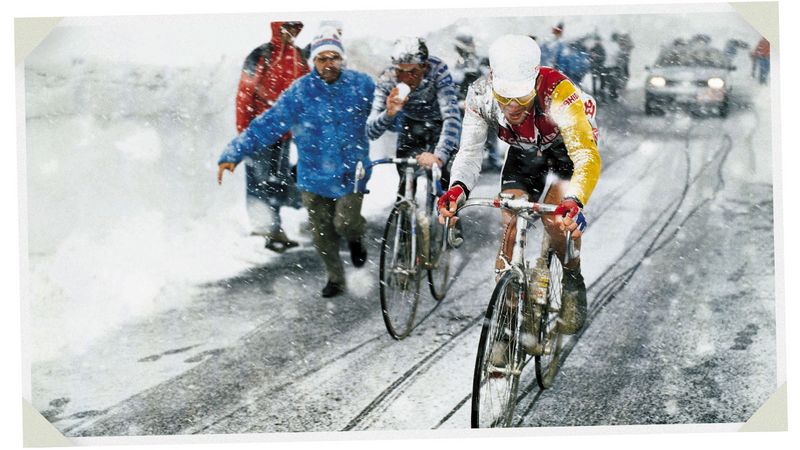

Mr Andy Hampsten

Mr Andy Hampsten, Gavia Pass, 1988. Photograph by Mr Graham Watson

Up until the 1980s, the only non-Italians competing in the Giro had still not travelled very far. They were French, Swiss, Belgian or, at a push, Spanish. But then almost by accident, a team from the US changed everything. “We rode like cowboys,” says Mr Andy Hampsten, who, as part of the legendary American 7-Eleven team, took the 1988 race. Hailing from the American Midwest, Mr Hampsten was undaunted by the metre of snow that graced some of the mountain stages of that year’s Giro (which, it is worth noting, took place in early June). The team were also better prepared, stocking up on out-of-season ski gear from local shops ahead of the 14th stage. “Cyclists now appreciate weather conditions by asking themselves the question, ‘It’s cold out, but is it Hampsten cold?’” say the Velominati.

Mr Roger De Vlaeminck

Mr Roger De Vlaeminck, Vajolet, 1976. Photograph by Sirotti

Yes, Mr Merckx won a lot of races and looks unbelievably cool in old photos, “but if I have to pick a Belgian from that time it would be Roger De Vlaeminck”, says Mr O’Brien. “That Brooklyn team [sponsored by an Italian brand of chewing gum], you still see people wearing the jersey.” Best known for his exploits in the Paris-Roubaix, which Mr De Vlaeminck won a joint-record four times, he took the Giro’s points classification jersey on three occasions. “His style, both on and off the bike, was impeccable,” say the Velominati. “There are four documented cases where women required medical attention after observing him stroll by in a trim wool suit and skinny tie.”

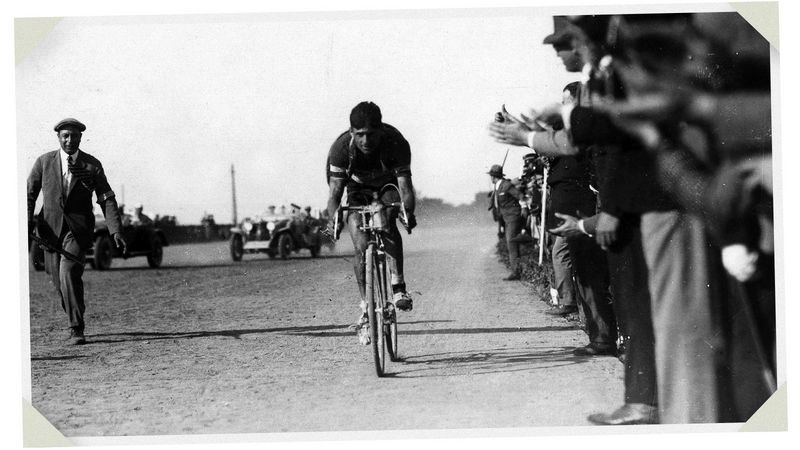

Mr Alfredo Binda

Mr Alfredo Binda, 1927. Photograph by Mondadori Portfolio

The first rider to win the Giro five times, Mr Alfredo Binda was a gifted time triallist and climber. He was also a trained trumpet player and worked as an apprentice plasterer. “Binda was a rider of unparalleled ability, of such unique talent that he dominated almost every race he entered,” says Mr O’Brien. “He was the complete package: powerful on the flats, imperious in the mountains, said to be blessed with a seemingly effortless pedal stroke and an easy elegance under pressure. The French rider René Vietto famously remarked that if Binda started the race with a glass of milk on his back, it would still be full at the finish-line.” He set the standard for his era and, indeed, the following 70 years. His record of 41 Giro stage wins was not bettered until 2003.

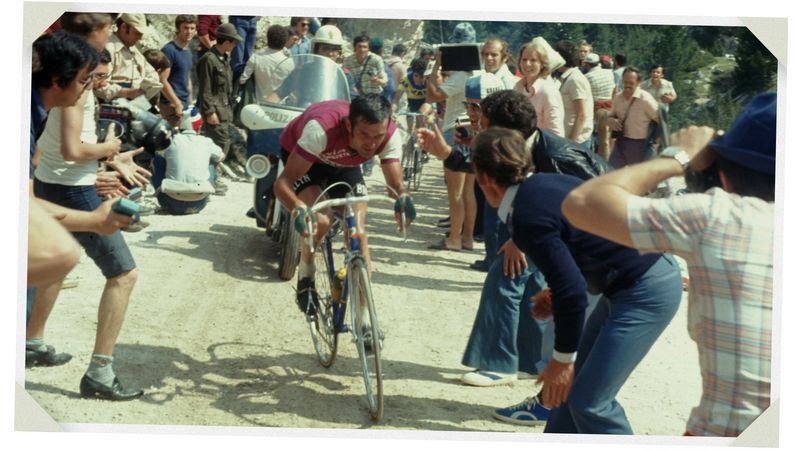

Mr Giovanni Battaglin

Mr Giovanni Battaglin, Duran Pass, 1980. Photograph by Sirotti

This Italian climber finished the Giro in the maglia rosa once – in 1981, the same year he took the Vuelta a España’s red jersey, on a stunning Colnago bike of the same shade – and while few have looked so good in the old azzurra of his national team, Mr Battaglin’s true colour was gold. Known for the glint of Rolex on his wrist and matching gold anodised toe clips and gold-plated bike forks, he wore such trappings with restraint compared with others on the professional circuit. Mr Battaglin was also one of the few riders to trouble the great Mr Merckx, especially when it came to the mountain stages. To make Mr Merckx break into a sweat, you had to be good – and Mr Battaglin was definitely that.

Giro d’Italia: The Story Of The World’s Most Beautiful Bike Race (Pursuit Books) by Mr Colin O’Brien is out now; The Hardmen: Legends Of The Cycling Gods (Pursuit Books) by The Velominati and Mr Frank Strack is published on 1 June