THE JOURNAL

Ferragamo family portrait at Castiglion del Bosco, Tuscany, 2007 Douglas Friedman/ Trunk Archive

Just as the slow-food movement changed eating habits, some Italians’ approach to business is finding followers around the world.

Speed is everything in the new economy. Speed of innovation, speed to market, speed to fail. In Silicon Valley plain old arithmetic or geometric progress is for losers. Google puts a two-year limit on projects at its Google X research lab. There is no time for lingering at the smoothie bar, no strolls in the California sunshine. It’s triumph or die. When the two years is up, each project is killed, spun out or licensed. Painted on the walls at Facebook’s headquarters are the words “Done is better than perfect” to urge its programmers always to keep shipping code.

Even the old hustle and bustle of Wall Street, of harried commuters pouring out of train stations, looks slow in a world moving at terabyte speed. Economists and politicians panic when growth of nations slows, as it is a harbinger of trouble.

But there is another way. A slower way of doing business, still working and still visible through the scrum at the top. It requires patience and long-term investment, the sacrifice of quantity for quality. But when it works, it can achieve extraordinary results.

Mr Pier Luigi Loro Piana (right), chairman and CEO, and his brother and co-chairman Sergio, Valsesia, Italy, 2008 Ben Baker/ Redux/ eyevine

The Loro Piana family began trading wool and textiles in the early 19th century, established the business bearing its name in 1924, expanded into retail in the 1990s, and eventually sold control to LVMH in 2013 for $2.6bn. In the years leading up to the sale, the two brothers who ran the company, Messrs Sergio and Pier Luigi Loro Piana, rotated their executive positions every three years to swap perspectives and maintain their energy. They once published a book titled Baby Cashmere: The Long Journey of Excellence to describe the extremes Loro Piana goes to to secure a supply of baby cashmere, which is gathered by combing the under-fleece of hircus goats raised in the Mongolian desert.

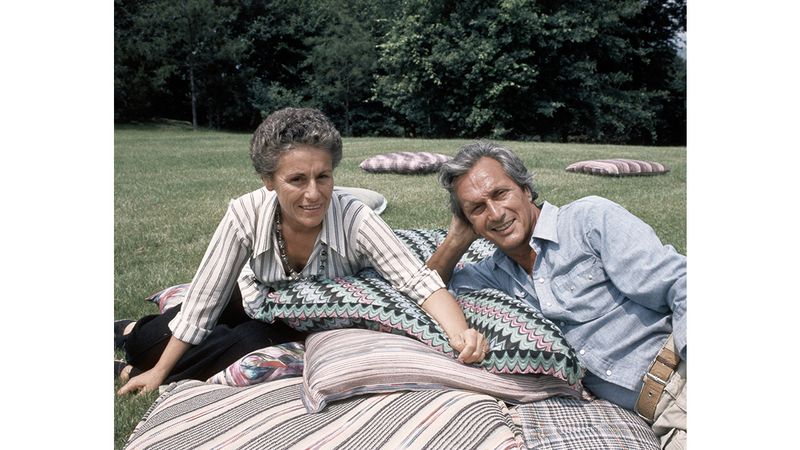

Mr Ottavio Missoni and his wife Rosita at their home in Sumirago, Italy, 1975 Sergio del Grande/ Mondadori Portfolio via Getty Images

Mr Ottavio Missoni, the founder of the Italian fashion brand, used to resist any efforts to expand the business too far from its artisanal roots in northern Italy. He saw the point of business as creating a happy and prosperous life for his family and would tell his daughter Angela: “Why do you want to work more? To earn more for what? What good is it if we don’t have time to spend it?”

Mr Oscar de la Renta used to insist on spending Sunday nights at his country house in Kent, Connecticut, before returning to Manhattan early on Monday morning. That extra night, he explained, gave him a chance to wander the paths of his garden, considering his trees. Many had been planted by people who never saw them grow to their full height, and he in turn planted trees that would flourish long after he died. Those Sunday nights allowed him to focus on what truly mattered in both his life and business, to avoid the ephemeral distractions of his ever-changing industry.

The notion of “slow business” has emerged, well, slowly from that of “slow food”, the movement founded in 1986 by the Italian food activist Mr Carlo Petrini. Mr Petrini objected to the arrival of fast-food chains in Italy, to their effect on agriculture, their treatment of the environment, and their assault on the traditional Mediterranean practice of carefully prepared and slowly devoured family meals. It is not to be confused with idleness or lack of productivity or even the poverty, which might follow a refusal to work. It is more about pursuing quality over speed, and tuning out those who demand their products and financial returns five minutes ago.

From left: Messrs Massimo and James Ferragamo, Diego di San Giuliano and Leonardo Ferragamo at Castiglion del Bosco, Italy, 2007 Douglas Friedman/ Trunk Archive

It is also about building strong foundations to the kinds of structures which can sustain patience over time. When the shoe designer Mr Salvatore Ferragamo died in 1960, his widow, Wanda, was just 38 and had six children aged two to 17. She buckled down to save the business, involving her children as they came of age. One of her rules was that all family members working for the company should be paid the same and have the same portion of company shares. This inhibited any bickering and has allowed the Ferragamo brand to reach its third generation of family ownership in rude health.

The Beretta family has been making firearms in Gardone Val Trompia in Lombardy for 15 generations, since 1526 when Mr Mastro Bartolomeo Beretta was paid 296 ducats to deliver 185 arquebus gun barrels to the Arsenal of Venice. The family may now flit across Europe and the Atlantic for education and business, but it is still rooted in the hills around Gardone.

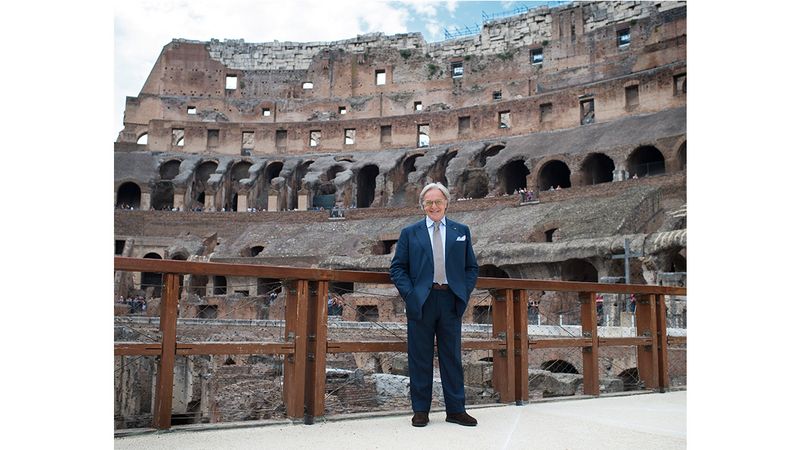

Mr Diego Della Valle at the Tod's restoration project at the Colosseum, Rome, 2008 Emanuele Scorcelletti

The spread of “slow” thinking from food to other industries is most apparent in fashion, whose profit margins and emphasis on brand and reputation have led certain companies to invest differently. Tod’s is still based in Sant’Elpidio a Mare, a small town in the Marche region of Italy, where shoes have been made for centuries. It was here that the grandfather of Tod’s current chief executive, Mr Diego Della Valle, first set up a workshop in the 1920s. The headquarters may be thoroughly modern, all marble and glass and decorated with modern art, but many of the employees are second generation. Well into his eighties, Mr Della Valle’s father used to ride through the corridors on his bicycle. The family’s motto, “Dignità, Dovere e Divertimento” or “dignity, duty and fun”, is made real by the benefits given to staff, the elegant workplace, the refusal to outsource manufacturing to China – and the Formula One Ferrari driven by Mr Michael Schumacher in 1997 which sits in a hallway. Tod’s business philosophy is that when the world pays for products marked “Italian-made”, it wants them actually designed and made in Italy, by Italians living a thoroughly Italian way of life.

Americans, a people known more prizing rapidity, are coming around to “slow” thinking, but it can often feel at odds with the traditional pace of American business. In 2009, in the thick of the recession, the Harvard Business Review turned to Ms Alice Waters, the chef and owner of Chez Panisse in Berkeley, California, to explain how “slow” practices could survive a terrible economy. Thirty-eight years in business, she explained, had taught her a few things. Borrow from friends and family and avoid banks if you can. Be thrifty. And keep deepening those relationships with employees, suppliers and customers. She lets her chefs share their work, so they have time to spend with their families, learning and travelling to improve their skills. They end up staying far longer than chefs at other restaurants. She never compromised on quality: “If it takes that much olive oil, it takes that much olive oil.” And she stayed loyal to farmers who delivered great ingredients. “We went right to the doors of the people who were taking care of the land. We met them and became friends with them and we knew we couldn’t live without them. We needed their food, and they needed our money. I’ve never argued over price… I want to hear what they think I should cook from their farm. I want their opinion about what is best. It’s not a waste of my time. We have a lot of customers who trust us to have this engagement.”

All kinds of trends now lurk in the shadow cast by “slow”, ranging from the enthusiasm for “heritage” products to “authentic” brands and “mindful” management. Some are for real, while others seem purely instrumental, a means to extract greater worker loyalty or higher productivity. There can’t be a CEO left on the planet who does not claim to meditate or pursue greater mindfulness. Ms Arianna Huffington claims in her recent book, Thrive, to have discovered the importance of sleep and avoiding stress to living a happy life. At 64, it’s better late than never. There are companies that advocate “doing well by doing good”, integrating charitable works with business in the manner of TOMS shoes, which donates shoes, clean water and medical care in proportion to the shoes it sells. A new “slow technology” movement argues for more “people-centered” devices, ones that are not hell-bent on overwhelming us with texts and streams of social data but actually improve our lives.

Shinola factory and shop, Detroit Shinola

The Detroit-based luxury goods company, Shinola, has made a virtue of starting up in post-recession Detroit and producing watches, bicycles, leather goods and shoe polish in a spirit of old-school American manufacturing. Its shops and factory are straight out of Raymond Chandler, designed to look as if nothing has changed since the 1940s. There is artifice here, in the fact that Shinola was founded by Mr Tom Kartsotis, who made his fortune with Fossil watches. Shinola is just four years old, but its story and products have been cultivated to suggest a far longer history. It boasts of being “analog in a digital world” yet sells briskly through its online channel.

But there is nothing fake about the hundreds of good jobs being created in a city that badly needs them. Poor old Detroit, and the old manufacturing firms of the Midwest, have had their fill of “fast” business, and “slow” seems to suit their rebuilding. Shinola’s journals are comprised of paper made by the family-owned Edwards Brothers Malloy of Ann Arbor, Michigan. Its leather goods come from the 110-year-old Horween Leather Company of Chicago. Its bicycles are made by Waterford Precision Cycles, a small company in Waterford, Wisconsin, run by Mr Richard Schwinn, the great-grandson of the founder of Schwinn & Co., the pre-eminent American bicycle-maker of the 20th century.

A favourite line in the slow movement comes from the comedian Ms Lily Tomlin: “The trouble with the rat race is that even if you win, you’re still a rat.” Going slow is not another way to win the rat race by fine-tuning certain aspects of your life or business to become more productive. It is about pursuing a different life altogether.