THE JOURNAL

While most actors reveal their tricks of the trade – perhaps posting workout videos, sharing photos from set, dissecting their process in interviews – LaKeith Stanfield makes a conscious decision to conceal his methods. “Imagine you went to a magic show, but before the magician did every trick, he showed you exactly how he did it,” he says. “Then the magic would not do anything for you.”

It’s a philosophy that feels almost radical in an industry where people have come to expect intimate, constant access to performers, from character breakdowns to their breakfast choices. Stanfield, at 34, represents something increasingly rare: an artist who insists that not everything should be consumable, that mystery serves a purpose beyond mere intrigue.

His latest project, Lynne Ramsay’s Die, My Love, finds him opposite Jennifer Lawrence and Robert Pattinson in what he describes as an exploration of “the liminal space between dream world and the real world”. It’s fitting territory for an actor who seems to exist in that same in-between space – present but elusive. The film, already generating awards buzz, examines postpartum depression through Ramsay’s distinctive lens – Stanfield plays Karl, the next-door neighbour who serves as a conduit into the main character’s shifting reality. It was a project that drew him in partly because of his desire to honour the process of motherhood, as a father of three.

“I walked with my wife [the model Kasmere Trice; they married in 2023] through her experience,” he says. “It was amazing and beautiful, and as a man you’re always trying to figure out how you can be as useful as possible in such a beautiful process. And then reading it through the lens of this script was very much from the perspective of a woman and what her journey might look like. I thought that was valuable, it spoke to me.

“When I read a script, I’m not necessarily looking for anything,” Stanfield says. “I’m seeing what is revealed to me.” His decisions about which roles to take on are anything but random, though. He filters them through a rigorous internal compass and consciousness that rejects projects seeking to “perpetuate harmful stereotypes about Black people, Black men, Black women,” he says.

“I do not like things that want to put us into smaller boxes and cause us to be seen as unhuman on the public stage.” His voice takes on a sharper edge. It’s a responsibility he carries deliberately, understanding that his choices ripple outward into cultural imagination. “I would love for my kids to grow up and see imagery that is more closely aligned with them than the things that I watched.”

It reveals the inheritance he’s working within – a lineage of Black performers who made strategic choices to expand possibilities for those who followed. When he met Sidney Poitier years ago, briefly and awkwardly approaching the legend outside a car, Stanfield understood he was encountering someone whose decisions had created the space he now occupies. While he’s grateful for the progress that came before him, he recognises there’s still work to be done.

“I would love for my kids to grow up and see imagery that is more closely aligned with them than the things that I watched”

Stanfield, who was born in San Bernardino, California and grew up in Riverside and Victorville, showed early performance instincts. As a child, he used to put on shows for his aunt. But it wasn’t until high-school drama class at 14 that he discovered something transformative – not just acting, but a community of people who understood emotional expression.

At 15, he enrolled at John Casablancas Modeling & Career Center in Los Angeles. A few years later, he landed his first role in the short film Short Term 12, the director Destin Daniel Cretton’s master’s thesis project that won a jury prize at the 2009 Sundance Film Festival. Between the short film and its feature-length adaptation, he worked various jobs – roofing, gardening, at a marijuana dispensary and as an AT&T salesman – before being called back to reprise his role in what would become his breakthrough feature performance.

Now, he operates with a selectivity that these expanded options afford him and his upcoming slate reflects this: Roofman, the true story of Jeffrey Manchester (played by Channing Tatum), who robbed McDonald’s restaurants by drilling through their roofs; I Love Boosters, about a ring of female shoplifters; Play Dirty, an action thriller with Mark Wahlberg.

“I have a tendency to get into these characters and I give it everything I got,” he says. “And I think that sometimes causes me to be exhausted emotionally. So, I like to have fun to offset that.”

Stanfield’s careful curation has resulted in a CV drawn to the weird, the esoteric and often the dark. From his breakout role as the enigmatic Darius in Atlanta – a character who seemed to exist on his own philosophical frequency – to his unnerving portrayal of the hypnotised Andre in Get Out, he gravitates toward roles that unsettle and challenge. His turn as FBI informant William O’Neal in Judas And The Black Messiah found humanity in moral complexity, while Sorry To Bother You let him dive into surreal social commentary.

In his approach to fame, Stanfield maintains what feels like old Hollywood boundaries. “My work is my work,” he says, matter-of-factly. “You go to work, and then you come home and you’re at home.”

When fans approach him on the street, moved by his projects, he finds satisfaction not in personal validation, but in the knowledge that collaborative art has achieved its purpose. “It is very much something I was a part of,” he emphasises, deflecting individual credit. “There’s a writer, there’s a director, there’s a cinematographer, there’s a personal assistant. There are so many people that come together to make projects happen and I’m just a part of that piece.”

“The hardest thing is to get out of your own way”

Music is where he allows himself to get more personal. That same drama class where he discovered acting also became the space where he first started sharing his early music CDs with fellow students who felt like outsiders, too. It was where he felt safe being vulnerable, understanding that his classmates would appreciate where his emotions came from.

His recent collaboration with Kid Cudi emerged from a mutual respect for the same thing Stanfield searches for in his characters: authenticity. “I’ve always loved what [Kid Cudi] was doing, marching to his own beat, being himself,” Stanfield says. His music, which he records under the moniker Htiekal – his name spelled backwards – is an emotional blend of rap and ethereal synth sounds. It’s where he’s able to be political, vulnerable and express different sides of himself.

“It’s more of an X-ray than any interview I’ve ever done,” he says. “I don’t really talk too much about personal stuff in the interviews. The music is my canvas to be able to really paint a clearer picture of some of the things that I’ve experienced, survived and learnt from.”

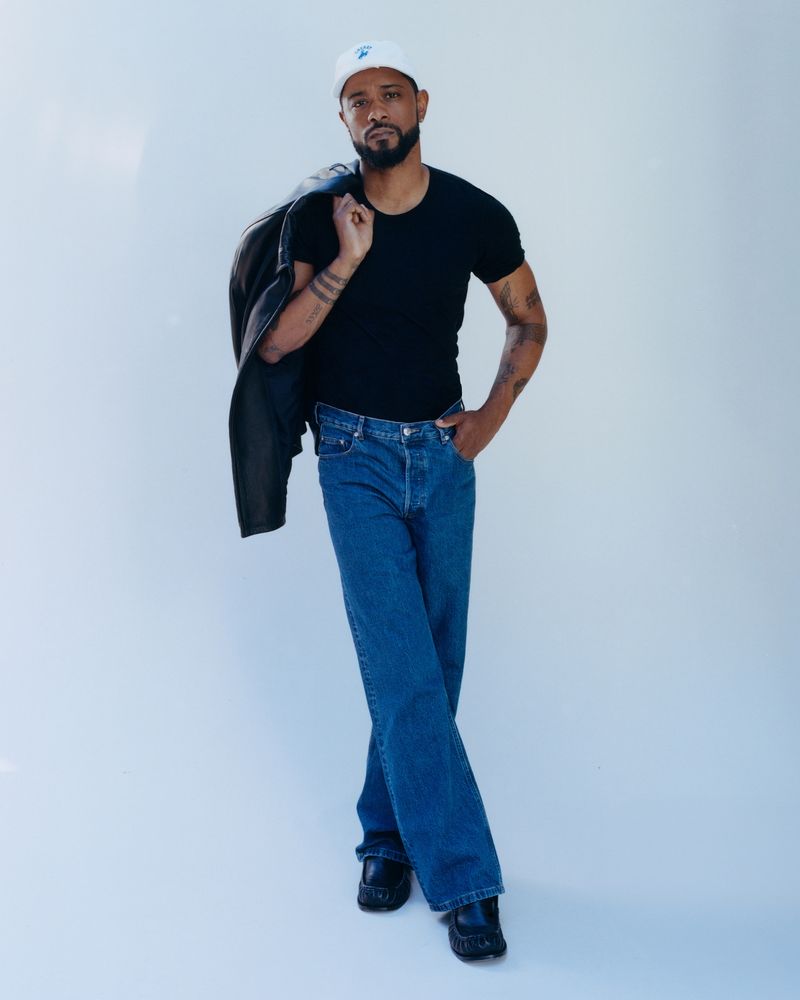

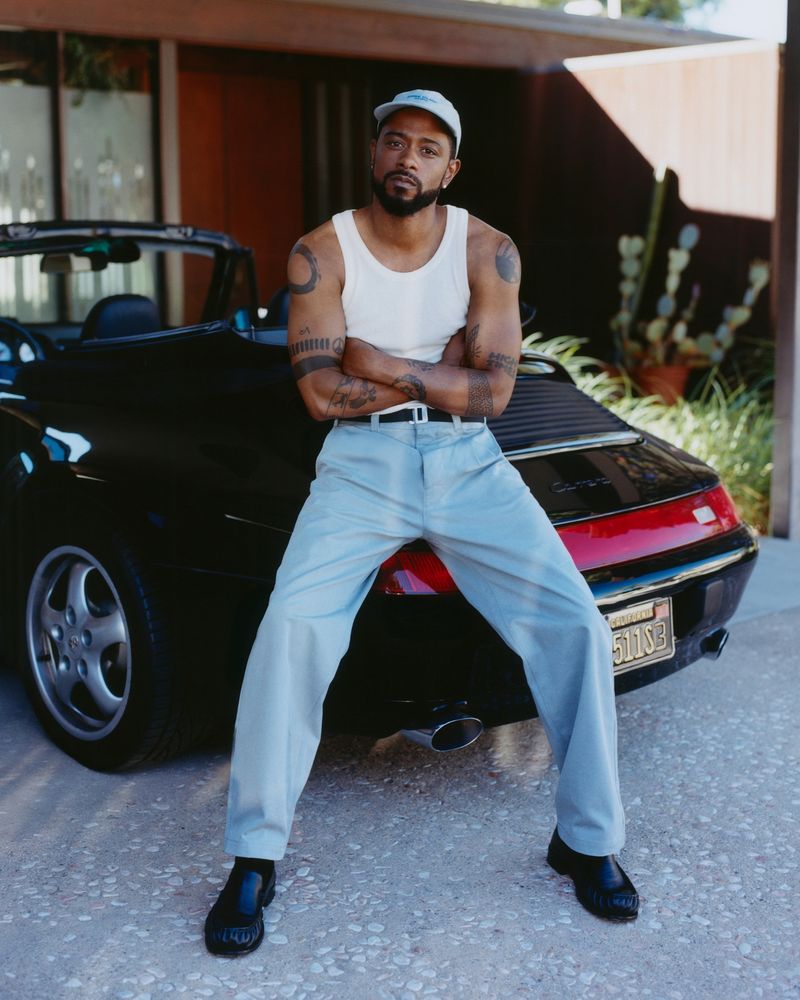

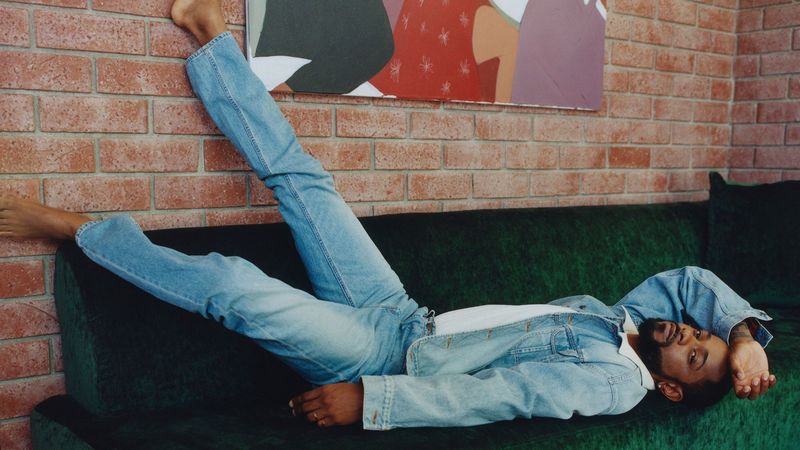

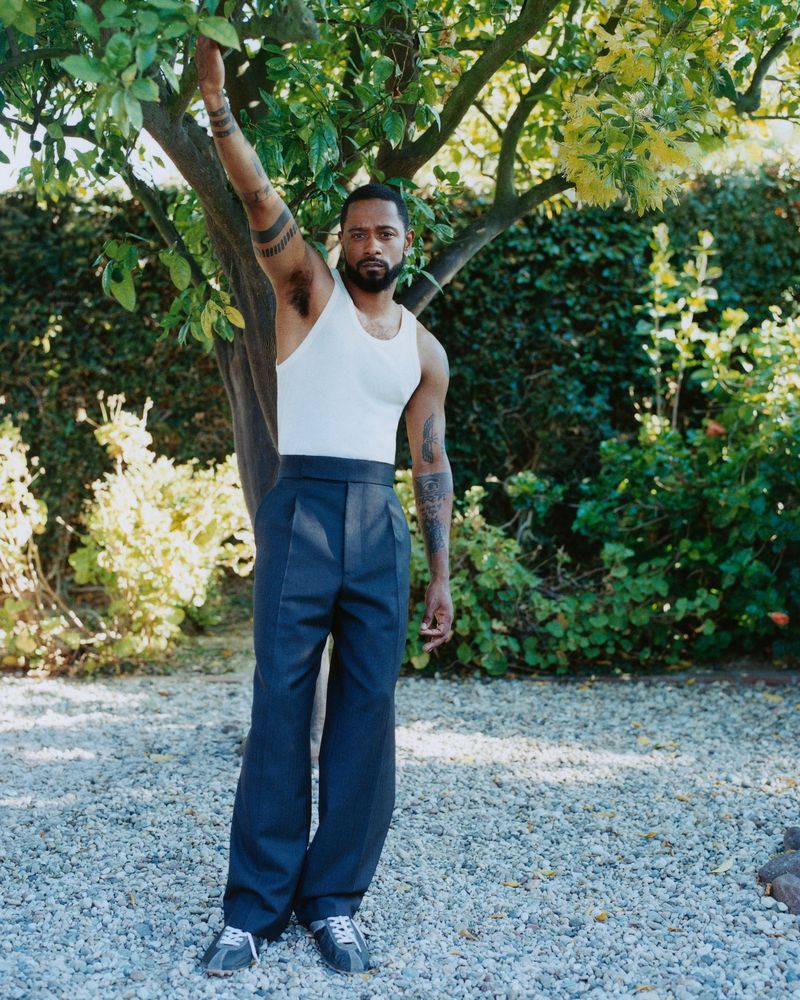

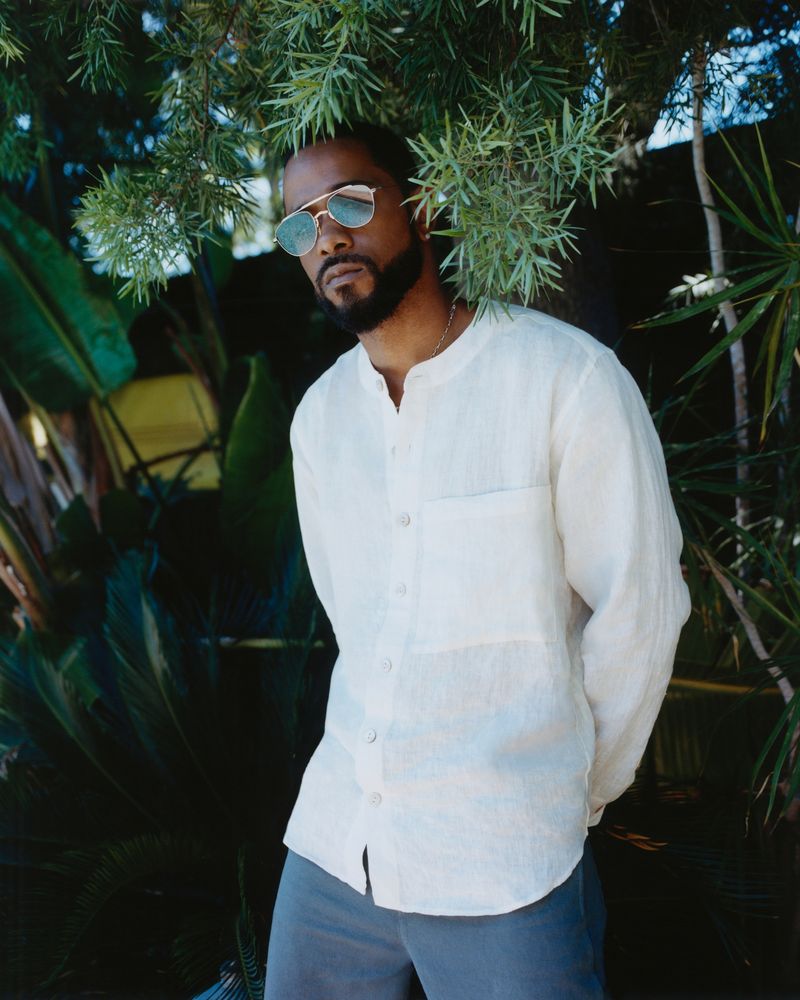

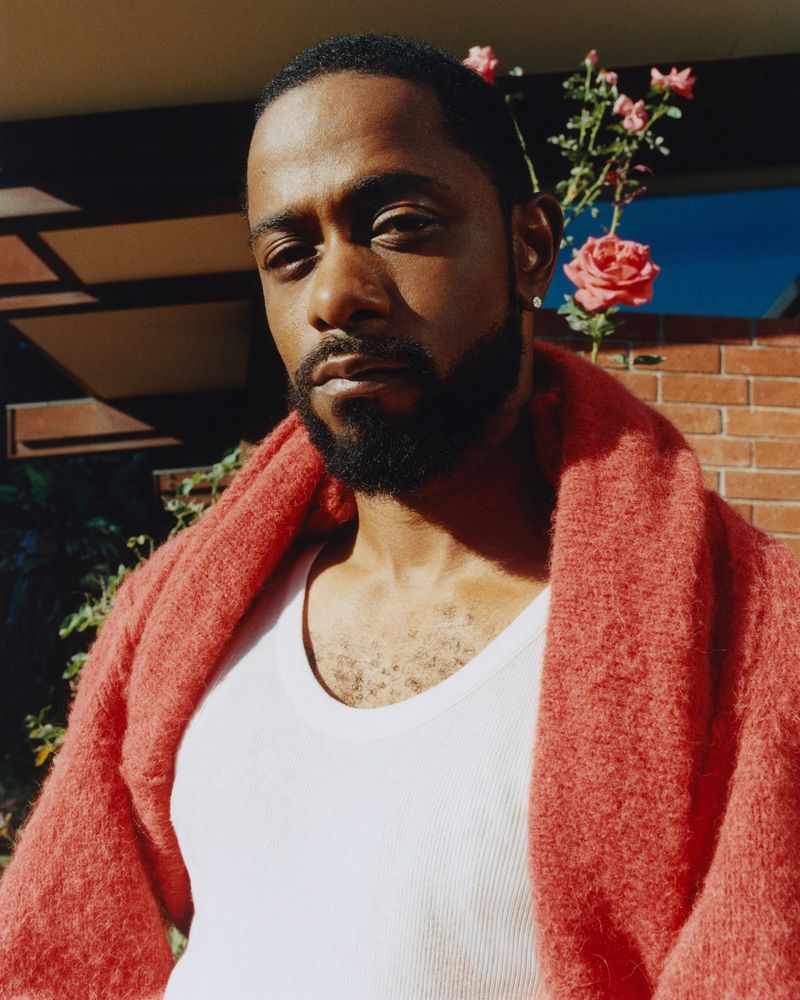

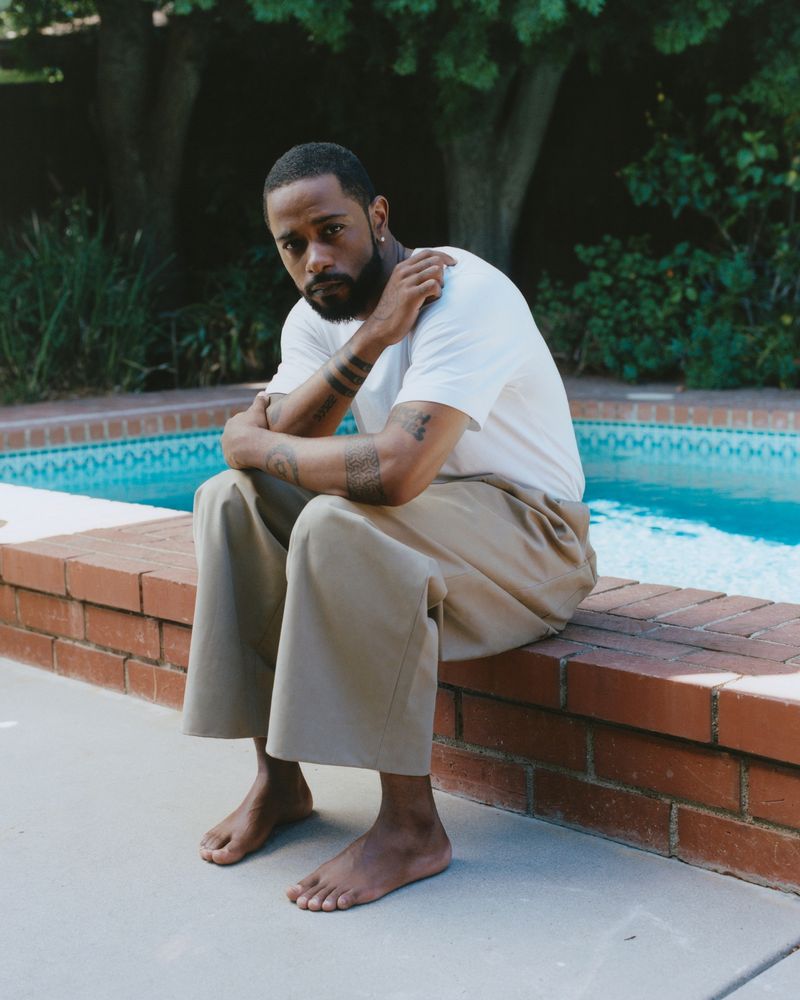

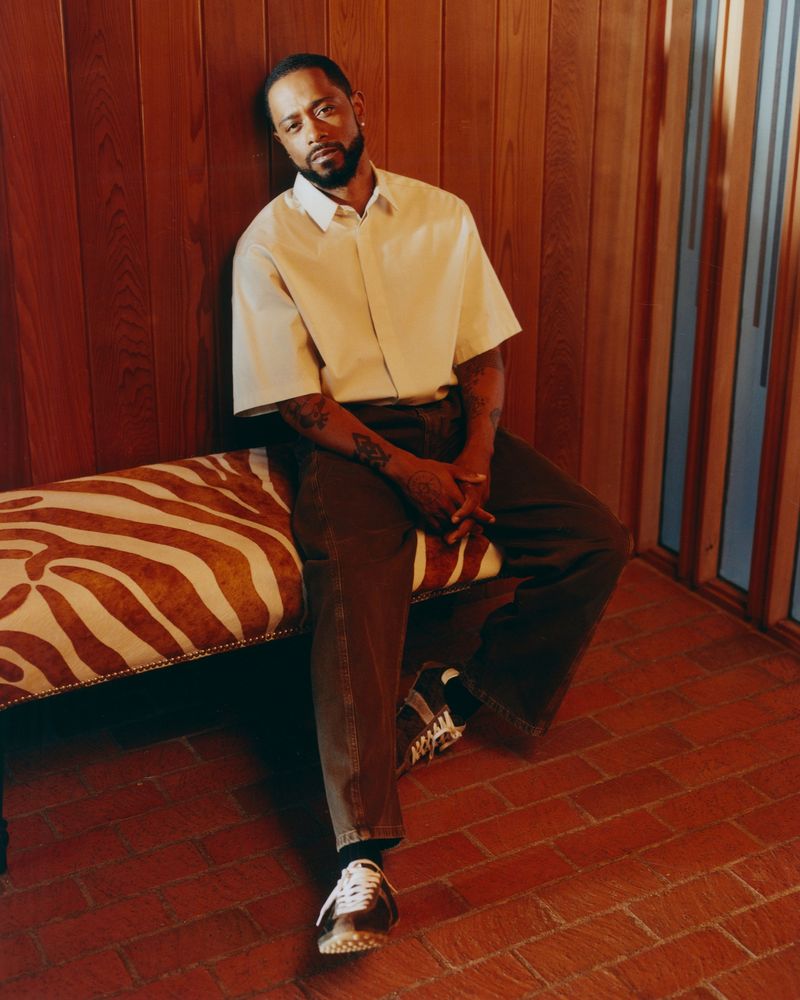

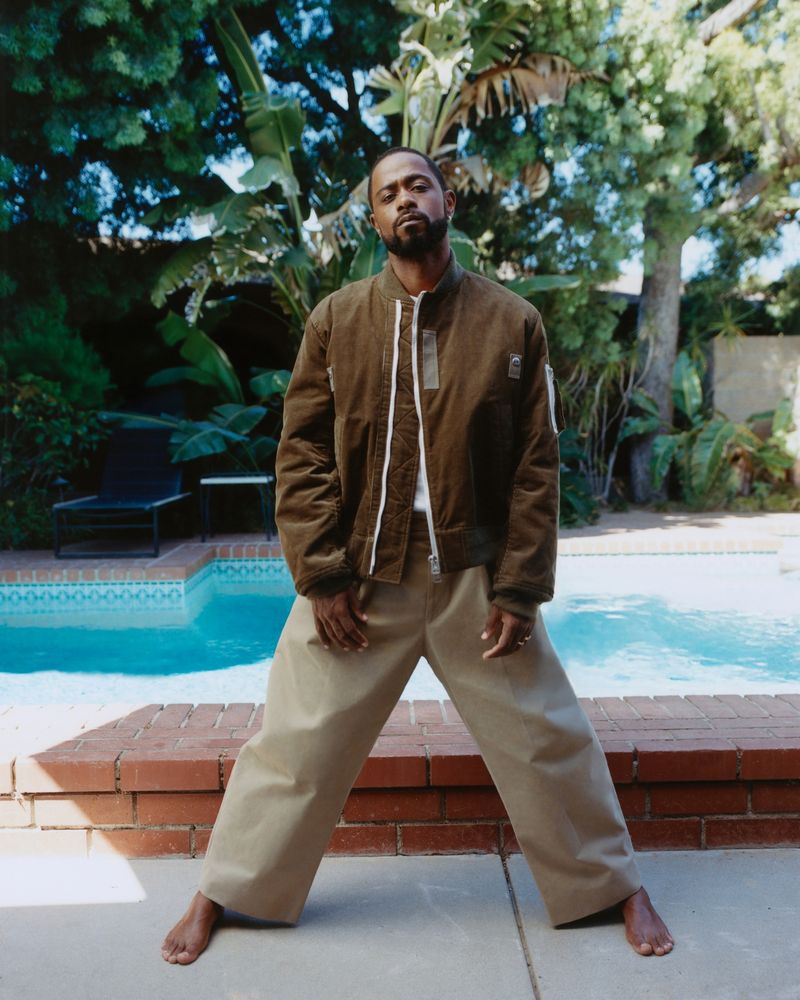

Fashion provides another outlet for the same expressive impulse that drives his artistic choices. Stanfield has become one of Hollywood’s best-dressed men precisely because he’s willing to go there – his red-carpet appearances alone prove his commitment to sartorial risk-taking. He’s a fan of brands such as Fear of God, SAINT LAURENT (his large-collared, 1970s-inspired jumpsuit to the 2021 Oscars was a standout) and Dior.

His relationship with fashion traces back to borrowing his older brother’s more coveted pieces as a child – sneaking into his Nikes when he was stuck with knockoffs, discovering how the right outfit could shift not just how others saw him, but how he saw himself. “It’s just expression,” he says, connecting fashion to his broader artistic philosophy. “Anyway, from whatever outlet, I must and can express, that’s what I’m interested in doing.”

“Sometimes it’s better just to live and immerse yourself in the magic of it”

“When I was younger, I kind of liked to stand out,” he admits. “As I’ve grown, I don’t want to stand out as much, but I like to feel good.”

To feel good mentally, Stanfield does breathing exercises, meditation and, most importantly, has worked on allowing himself to feel his emotions. “It’s a skill you develop,” he says of emotional processing. “The hardest thing is to get out of your own way. A lot of times feelings can feel counterproductive, but at the end of the day, we’re all human beings. You’ve got to feel. It’s just a stronger, easier skill to implement. Not all feelings are bad, some are good and you’ve got to feel those, too. I’ve been training myself to do that.”

Part of that training included getting sober. Stanfield has spoken openly about his struggle with alcohol addiction, which he reckoned with during the filming of The Harder They Fall in 2020. “I had become completely dependent upon it,” he revealed in a 2022 interview with GQ. “To the point where I wasn’t able to move or function a whole day without having it.”

Such an intentional self-care practice seems essential for someone who gives everything to his characters while maintaining boundaries around his personal life. He speaks about his three children and wife with deliberate brevity, protecting their privacy while acknowledging their central importance. “My private life is something that I’ve grown to value more and more,” he says. “Sometimes you have to pour back into yourself.”

He does give a glimpse into his domestic normalcy, though – movie nights with his wife and his concerns about raising children in the digital age: “It’s important to protect them from the internet.”

What emerges over the course of our conversation is a portrait of an artist who has found ways to be fully present in his work while drawing boundaries and retaining a sense of elusiveness beyond his roles – it’s a distinction that allows him to tell stories without sacrificing the self that creates them. Stanfield demonstrates that authenticity doesn’t require total transparency and, in an industry where Black performers are often expected to be perpetually available for consumption and explanation, his insistence on maintaining mystery and distance feels like its own form of resistance.

“Sometimes it’s better just to live and immerse yourself in the magic of it,” he says.

Play Dirty is available to stream on Prime Video from 1 October; Die, My Love is in cinemas from 7 November