THE JOURNAL

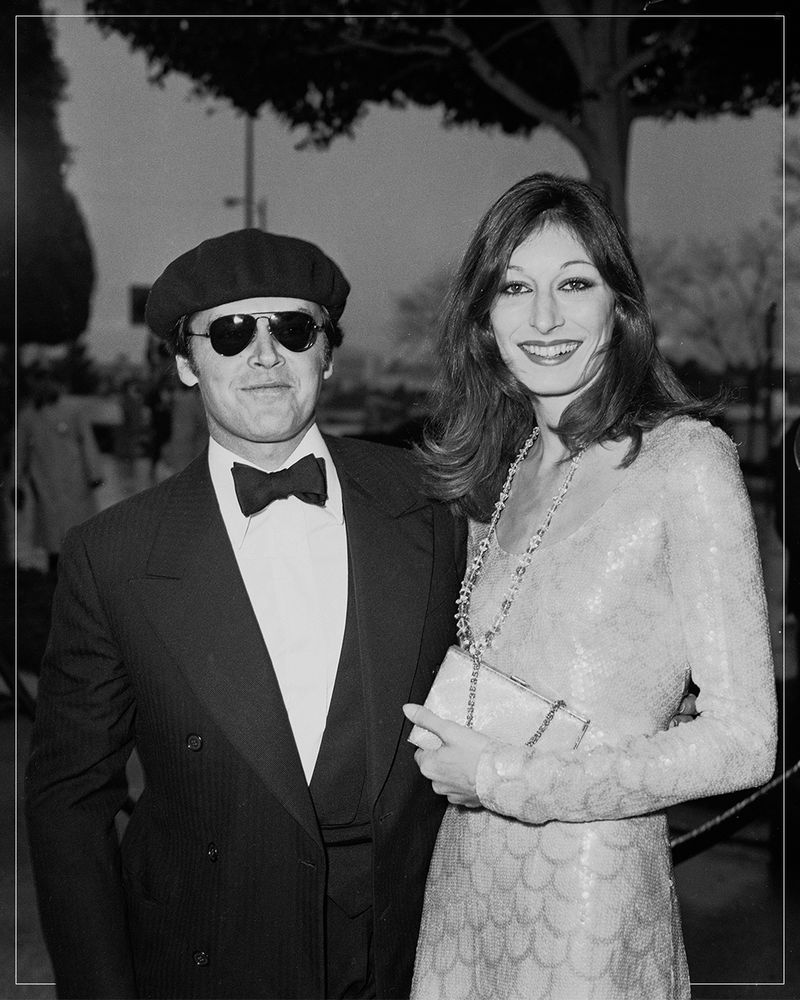

Mr Jack Nicholson arrives at the 47th Academy Awards, Los Angeles, 8 April 1975. Photograph by Mr Michael Montfort/Getty Images

You’re arriving at the most glitzy of awards shows, the kind created by the founding fathers of your industry in 1929 and still ruled over with dynastic glamour by the moguls who ran Hollywood from the beginning. You happen to be Mr Jack Nicholson, raffishly charming, on the Academy Awards red carpet: the ultimate outsider-turned-insider. What do you wear?

Nicholson’s answer was this: a combination of the traditional and the insouciant. He wore a respectable black tuxedo with a crisp white shirt and black bow tie, and then, to add a little spice, dark sunglasses and a black beret.

The year was 1975, and such was the strength of American filmmaking that it was a rare year in a rare decade of nearly perfect Oscar nominations: The Godfather Part II,_ A Woman Under The Influence_ and The Conversation, among others. Nicholson had been nominated for Best Actor for his remarkable role as a private detective in neo-noir Chinatown. And though he did not take home the statue that night, his career rise had been stratospheric – he had already been nominated three times in the past five years (and once for Best Supporting Actor).

In fact, Nicholson would go on to become the most nominated male performer in Oscars history. In other words, he had made it, and as if to cement this fact, on his arm was the sleek, diaphanously gowned Ms Anjelica Huston, daughter of Hollywood royalty Mr John Huston.

Mr Jack Nicholson and Ms Anjelica Huston at the 47th Academy Awards, Los Angeles, 8 April 1975. Photograph by Fotos International/Getty Images

But Mr Nicholson had not been on a straightforward road toward mainstream recognition, and both he and his style nods made that very clear. He had made a career acting in and writing B-pictures and exploitation films, not breaking out in a major role until he was 32. That role was hippie game changer _Easy Rider _(1969), helping to shift the bellwether of an entire industry into rebellious territory.

Nicholson gained rapid entry into radical-chic 1970s Hollywood, making fast friends with the likes of Black Panther Party founder Mr Huey P Newton, whose style influence – the beret, that is – seems hard to deny here. Nicholson’s nod toward the political activism of his generation spoke to his defiant attitude toward Hollywood schmoozing. With his permanently-raised eyebrows and knowing smirk, there was always something devilishly IDGAF about Nicholson that is clearly signposted by his choice of headwear.

After being nominated so frequently, Nicholson seemed less interested in the stiff formality of the occasion, allowing for more idiosyncratic style choices outside the realm of regular awards menswear. He got to have a bit of fun: he wore dark-tinted glasses that he was not inclined to remove, with the kind of confidence that a man wearing sunglasses indoors must have to ever get away with it. As Nicholson himself explained, he once saw the legendary Mr Fred Astaire put on a pair of shades after he lost out on an acting award, and figured: that was a great idea. “Sunglasses are a part of my armour,” he has said of his near constant accessorising.

As the counterculture era ploughed forward, men turned up to awards shows in more overtly 1970s gear: frilly shirts, enormous lapels, and even blue jeans, which would have been unthinkable at a black-tie event even five years before. But unlike many of his contemporaries, Jack Nicholson opted for a more quietly timeless look. His choices for the 1975 Oscars are less radical than they are subtly transgressive, walking the sartorial line between the conventional and the bold, the well-dressed and the unbothered. In his clothes as in himself, Nicholson combines the glamour of a bygone era with the fresh-faced rebellion of what was, in 1975, a very new kind of Hollywood. It would be another year before Mr Nicholson would win his first Oscar, for One Flew Over The Cuckoo’s Nest, but he won the night in 1975.