THE JOURNAL

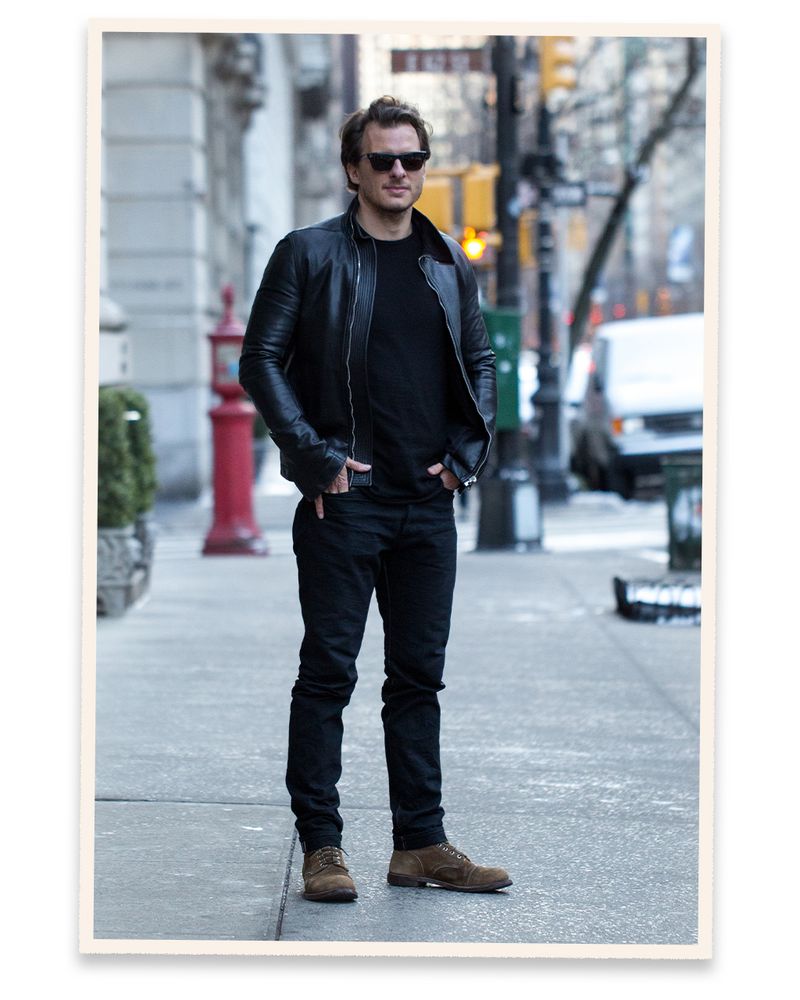

From left: Mr Chris Wallace in Chimayo, New Mexico, c. 1986, photograph courtesy of Mr Chris Wallace; New York, 2019, photograph by Mr Christopher Fenimore; Echo Park, Los Angeles, 2003, photograph by Mr Paul Jasmin, courtesy of WM Artist Management

This essay by our US Editor appears in our new book, The MR PORTER Guide To A Better A Day. Proceeds from the sale of the book will go to our Health In Mind fund, which supports men’s mental and physical health initiatives.

This may sound crazy, especially for someone who has worked as an editor at fashion-y magazines for over a decade, but I’m not really all that into clothes. Tell the truth, I probably think about style less than you. And, fashion? I’ve never met him. Even that most fundamental interaction with clothes – getting dressed in the morning – is a blur. All I want is to wear something that makes me feel like the person that I tell myself I am, and then not to think about it again for the rest of the day.

To that point, what I am interested in, more so than anything else, is identity – mine and just about everyone else’s: who we are, who we project ourselves to be – all those characters that we play. And, of course, clothes are the best way of getting into character; the best way of exteriorising taste, signifying values. In that way, anyway, clothes really do maketh the man.

So, what happens to you, your self and past selves then, if your clothes… disappear? Not by any willful, Ms Marie Kondo-style exorcism, but suddenly, in one moment and forevermore, they simply vanish? Like, gone-gone. From one day to the next, 10-year-old denim, gone. Gone, the bespoke suits. Gone the unmentionables. The accessories, the sentimental oddities: gone. Gone the clothes you’ve worn to be all the versions of yourself you’ve ever known, the only sort of memorabilia of your 40 years on Earth. Poof.

Last year, after a bit of a rough break up, and a move so long and dreary that Mr David Lean would’ve found it boring, I finally opened up my bags to find that I was missing, well, everything. Suffice to say that, when we split, I was in a rush to get gone and my ex was eager to have every piece of me deleted from the scene. Ergo: gone. Everything gone. Everything but the very core, the clothes I’d set aside to wear during the move, the clothes that were close at hand, the most durable – a pair of Levi’s, a pair of Red Wing Shoes, a few sweaters, and my Rick Owens jackets. A good core, the kind of garments you could wear through any sort of apocalypse, even one a little more severe than my petty, personal Ragnarok. But a repertoire maybe a tad… essentialist for a modern metropolitan life. Prohibitively so, in fact.

“If the clothes make the man, and I can begin my wardrobe again from the beginning, who in the world was I supposed to be?”

So, to shop! But where even to begin when one needs everything? There is no real beginning to any wardrobe, but, in this instance, there was a ticking clock of necessity to act as my guide. During the dread middle of winter in New York, the very first thing I needed was a coat. I have somewhat ironically always been a buy-it-once-buy-it-for-life guy, wanting only pieces that will outlive me, or at least accompany me for as long as I require them – which has tended to hamper explorations into flash and trend. To be honest, I’ve always been slightly cautious of even marginally directional clothing, feeling more comfortable in trad classics. And yet, I’d grown very used to wearing my Rick, so the coat I got was a very wild cloak from Mr Owens, and I think I wore it every day for the rest of the season. (I love it beyond mention.)

I loved it more than most of the other things that had survived the great purge, in fact, and so it inspired me to edit still further. If I was going to be so deliberate about what was in my wardrobe, I thought, shouldn’t I subject everything to the same rigorous selection process? (Maybe the new me was an athletic goth?) And so, my belongings grew even lighter still as I threw bad tees out after good suits, light enough that they could all fit into a single Rimowa, light enough that I could see the entire collection from a bird’s eye view and think about them in toto. Which led me to wonder, if the clothes make the man, and I can begin my wardrobe again from the beginning, who in the world was I supposed to be?

“Every morning, I would wake up and have to reboot myself, installing seemingly new software of beliefs and behaviours the same way I was putting on my T-shirts and jeans: half-heartedly”

“The challenge of modern freedom, or the combination of isolation and freedom which confronts you,” writes Mr Saul Bellow’s narrator in Ravelstein, “is to make yourself up.” Whole cloth, as they say. From scratch. Which we do (or at least I have to do) every morning, every time we dress ourselves up to greet the world, whether we are dressing to suit a mood or suit an occasion. My re-wardrobing situation felt like that daily application of identity on magic mushrooms – all of my choices seemed over-fraught, overly meaningful, definitive in a way that made me terribly uncomfortable, but also incredibly intrigued. Just think of the potential versions of me dwelling in all those un-bought clothes…

Walking around London’s Mayfair on a work trip, I started shopping for identities the way others were for brollies and whatnot. Like, look at those elegant gentlemen I see walking around in hoary old Anderson & Sheppard suits and their Cleverleys – looking like latter-day Sir John Gielguds – isn’t that who I’ve always aspired to be? Or am I, at heart, just the same jock-y Angeleno kid I was in long-sleeved Stüssy tees, baggy shorts and tie-dye socks? Or what of this seeming louche former spy now working in a late-night casino – all Haider Ackermann everything – no need to wrap it up, I’ll wear it out.

And so on, ad insanium, until I’d frightened myself into a kind of stagnation. Thinking of every option, every me available on the shop rack, I was too overwhelmed, too afraid to commit to any one personality for fear of something like existential buyer’s remorse. Every morning, I would wake up and have to reboot myself, installing seemingly new software of beliefs and behaviours the same way I was putting on my T-shirts and jeans: half-heartedly. But still, life made its demands regularly: I had a hiking trip, a beach trip, a ski trip and a fancy dinner to equip myself for. Inaction wasn’t an option, but the idea of shopping seemed like science fiction. So, instead of moving forward, I went back in time, pulling up old #tbt pics to see if, maybe, the direction in which I ought to be headed might not have already been set forth by the various mes I’d dressed up as in the past.

Mr Wallace in Cape Canaveral, Florida, c. 1988. Photograph courtesy of Mr Chris Wallace

It turns out that when I was a kid, I loved playing dress up. Looking back at pictures of the clothes I wore between say five and 15, it’s as if every day was Halloween and I really loved outfitting myself as the characters I wished to be.

In kindergarten, I wore the silver lamé-like onesie I’d gotten on a trip to the Kennedy Space station for like a month straight. Then of course there was the Return Of The Jedi-era Luke Skywalker looks – black cotton hoodies and kimono-y robes with my bowl cut mop. On vacation with my dad in New Mexico in the late 1980s, I dressed like a cowboy, replete with full bolo tie and 10-gallon hat. By the beach in my teens, I wore puka shells. As a skater in junior high, it was acid-washed denim and oversized logo tees. Costumes everywhere as far as I looked…

But, more even than my apparent Zelig-like attempts to melt into a scene, to disappear into a world as if I was meant to be there – as if I belonged – my childhood dressing-up was, I think, an attempt to try on personality traits and types, to discern which might best fit. (Which, on reflection, made complete sense – coming as it was from someone who spent years writing a novel called The Chameleon, about someone who shapeshifts to fit into whichever milieu he finds himself.)

Unsure of who I was, or could be, I suppose I was shopping for facets of me-ness. Perhaps I imagined that if I at least got in costume as every passing character I found appealing, I might pick up a few keepsakes by way of style, personality and behaviour that would better equip me to face the world. And I’m not sure that process of trial and error has ever really stopped. I’ve just gotten older and lazier.

In my more recent pictures (of the last 10 years or so), the outfits I’m wearing break down into three distinct styles, three characters: first there is the workaday classic man, wearing what Mr Andy Warhol called the “Editor’s Uniform” of dark blazer, Oxford shirt and jeans, which mostly made me look like your seventh-grade history teacher; then there is what I might’ve imagined to be Off-Duty Han Solo, but rendered me closer to Villain number six in a bad Mr Nicolas Cage movie – henley, leather jacket, jeans and boots; and the last is my James Bond on vacation scenario – aloha shirts and linen things – in which I ended up resembling Bond’s far less cool quartermaster “Q” going incognito.

Not exactly a bravura style performance, and still as I began to piece my wardrobe back together, I found that I continued to hew toward that trio. I was re-buying the wardrobe I’d by chance stolen my escape from – again with the henleys and dark denim, again into the tailored clothing, and again, for my sins, heavy on aloha shirts. It was with a kind of doomed disappointment that I figured that these specific threads ran through my taste like electromagnetic lay lines, that I was always destined to tend toward these poles.

Mr Wallace in New York, 2017. Photograph by Mr Christopher Fenimore

I was made even more acutely aware of my re-outfitting conundrum by, firstly, working alongside a slew of clotheshorses at a men’s lifestyle magazine – but also by simply existing in New York City, the American capital of vanity and self-importance, where so much of our self-branding and personal self-worth is projected by both our person and style. At several points, these competing pressures made me want to throw up my hands, to just opt out. Tees and jeans forever, the world be damned.

But there were moments when I did make some sort of headway, moments during shopping or stock taking of my incrementally expanding wardrobe, when I was able to recognise certain items as being essentially me. There were, for example, things that I had learned about myself, and which manifested in preferences for particular pieces of clothing: for knobbly, woven textures on my suits, to make a bad example, or for brown suede boots above all other shoes, to make a better one. Even more specifically, at my current rate of travel – at least twice a month – I go through security a lot, and I’ve found that, within the genus of suede boots, I prefer the species chukka and desert for travel days (soft, few lace holes so that they go through metal detectors easily, and go off and on simply if needs be). So, progress, right?

Well, in keeping with tradition, every time I have taken a step forward, toward understanding my style, and taste – and thus myself – I have spiralled backward like a poked balloon let loose. And this last, most recent time was probably the worst, and most… comprehensive. Even as I was making tiny, somewhat specific choices about socks or shirts or whatever, it began to dawn that I was getting no closer to any sort of real me-ness. What sort of identity is it to choose option A from four similar options in a multiple-choice question? Where in there is anything that we have come to understand about style, about character and personality? Again, came the urge to just disappear from the world of clothes, to vanish the way a man in a grey flannel suit might have vanished in the 1950s.

Of course a grey flannel suit is no longer “the grey flannel suit” of metaphor – if I wore that to the office, let alone to a dinner party, everyone would ask me why I was so dressed up. So how now to get away? How to both disappear into our contemporary world and disappear into myself?

Then, with a kind of revelation, I came, in my search through old pictures, onto a period – my twenties, when I was living in LA, during and after graduate school, working in a restaurant and making short films – in which I dressed in a uniform of Goodwill suits with jazzy shirts and sneakers.

Right away, I remembered feeling entirely at home in those clothes – dressed up enough to go into any scenario (and not be asked about it tediously), casual enough to be me, specific and referential enough to make me feel like I was in a conversation with the characters to whom I aspired, in communion with the many mes I hoped to be playing. And as soon as I had, this feeling of comfort – of exaltation, really, of discovering this moment in time, I felt another, nearer chime.

Sitting in my office, looking at pictures, I was wearing almost the exact same clothes. The suits were a bit nicer now, the jazzy shirts were made by Dries Van Noten, but here I was again, dressed, for the first time, just like myself.

It wasn’t exactly the kind of revelation that cures all present and potential worries (the student loans are still there, and I still lack for a good safari jacket and chef’s knife), but it was the kind of clouds-parting pause that made me feel like the decisions to come, the existential crises ahead would be a little less severe anyway.

The next morning, as I dressed, in what I now teased myself was my signature look, I started thinking of other things, everything thing else, in fact. And now I can happily never think about it again – at least, that is, until the fall.

The MR PORTER Guide To A Better Day_ (Thames & Hudson) is out now_