THE JOURNAL

Mr Jaden Smith at Paris Fashion Week, 6 March 2018. Photograph by Adam Katz Sinding

In 1964, the fashion designer Sir Hardy Amies declared that “jewellery for men is always dangerous ground. It is too dull to give the advice that it should be plain and expensive.” These were prescient words. Nearly 60 years later, jewellery for men is proving to be anything but plain and is becoming more adventurous by the day. Gone are the days of discreet chains and the odd kitsch cufflink. Banished is the era when mainstream showiness stretched only so far as an emerald tie pin or a signet ring.

Right now, men’s fine jewellery is inventive, ornate and full of DIY flair. It involves pearls, beads, turquoise, enamel and a rainbow of gemstones. It stretches from silver necklaces, as worn by Connell in Normal People, to delicate flower bouquets and the odd friendship bracelet thrown in along the way. If you’re rapper Lil Uzi Vert, you can forgo conventional setting and instead have a pink diamond implanted in your forehead. Other poster boys who’ve plumped for less invasive options include Messrs Jaden Smith, A$AP Rocky, Justin Bieber, Billy Porter and the boys from BTS, all of whom have embraced brooches, pendants, chokers and dangling earrings with gusto.

It would be flippant to suggest this is unprecedented. Trend reporting relies on certain tropes, one being to claim a newly popular garment or accessory as something fresh and shiny, thus implying a degree of never-seen-before novelty. As with all trends, this one is a circle rather than a straight line. Men have embraced things that glitter and grab attention for centuries. In his enlightening book Jewelry For Gentlemen, Mr James Sherwood observes that “as a brief canter around the British Museum will demonstrate, men of power have adorned themselves with yellow gold and gemstones since the time of the ancients. Celtic thanes, Egyptian pharaohs and Chinese emperors all chose sartorial treasures to display their wealth, refinement and status.”

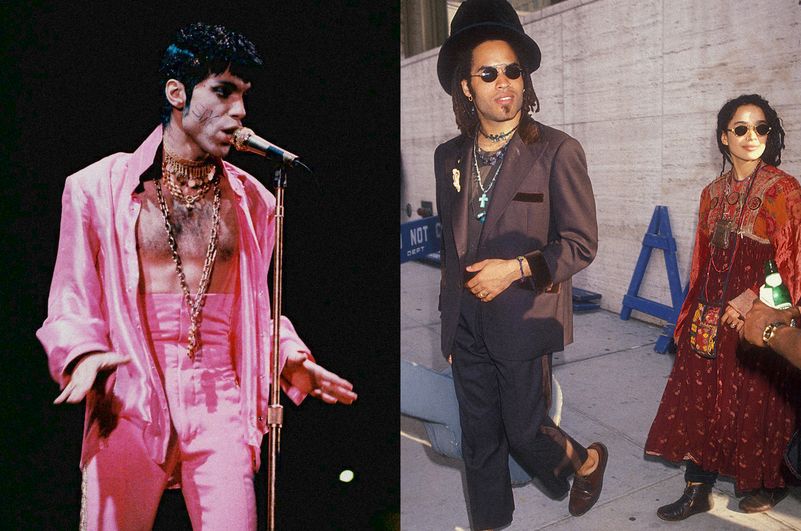

Left: Prince performs at the “The Ultimate Live Experience” tour, Wembley Arena, London, 4 March 1995. Photograph by Mr Pete Still/Redferns via Getty Images. Right: Mr Lenny Kravitz with Ms Lisa Bonet in New York, 5 June 1989. Photograph by Mr Michael Ferguson/Globe Photos via ZUMA Press

You don’t have to go that far back to find men who were partial to a bit of finery. Sherwood cites a number of men from more recent history who took great pride in their bling, from Edward VIII, whose diamond dress set rivalled some of the gems owned by his famously festooned wife Ms Wallis Simpson, to Maharaja Sir Bhupinder Singh of Patiala, who, in the 1920s, commissioned a five-tier diamond and ruby necklace from Cartier with a 234.6-carat yellow diamond at its heart.

These are examples of extreme wealth, all pizzazz and big money. Other more subversive examples might include musicians such as Prince and Mr Lenny Kravitz. The former draped himself in crystals and chains, not to mention that famous love symbol pendant; the latter was enjoying the dramatic effects of strings of pearls long before fellow singers Messrs Pharrell Williams and Harry Styles got in on the act.

“Men of power have adorned themselves with yellow gold and gemstones since the time of the ancients”

Kings and princes aside, a lot of the more outré jewellery choices made in the 20th century helped to designate the men wearing them as somehow opposed to the mainstream. The hippies had their beads. Punks had their spikes and chains. Nirvana frontman Mr Kurt Cobain once wore a necklace strung with plastic dolls’ heads. Elsewhere, jewellery signalled a complex relationship with the mainstream. Run-DMC’s thick gold dookie chains asserted their right to the same wealth, status and respect that all the powerful men who came before them had claimed for themselves.

There has been a recent sea change in how we view men’s jewellery. For one, it’s no longer niche, either by consequence of wealth or marginality. Two, there’s an increasingly (and thankfully) indistinct line between what is considered masculine or feminine. As the boundaries of menswear and womenswear continue to blur, jewellery has undergone its own transformation. If anything, it’s become a sort of gateway drug, offering a gentler way to ease into the possibilities of gender-fluid attire. Now all options are open to the wearer, whether one wants folksy comfort or full-on flamboyance.

Left: Mr Evan Mock at Paris Fashion Week, 2 October 2021. Photograph by Mr Edward Berthelot/Getty Images. Right: Giveon attends the 2021 Met Gala benefit “In America: A Lexicon Of Fashion” at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 13 September 2021. Photograph by Mr Taylor Hill/Getty Images

There is also a homespun element to modern jewellery that seems to have come to the fore. Just as one can trace trends such as patchwork or rustic knits to a pandemic-induced interest in craftiness, so, too, one can read into Carolina Bucci’s signature Forte beads a desire for simplicity and play. These are bracelets designed to look homemade, like the friendship bracelets we shared as children. They are comforting, reminiscent of adolescent experimentation and 1990s nostalgia. Like the ever-popular pearl, they have a softness that adds a note of delicacy to an outfit.

Plenty of innovative new jewellery designers are also emerging. Austin, Texas-based VADA specialises in beautiful rings and necklaces made from recycled precious metals, while Fernando Jorge’s fluid, sensual designs contrast with the machine-tooled aesthetic of Messika’s “Move” range of bracelets, rings and pendants, which feature precious stones that glide freely in their settings. Such designs speak to fashion’s status as a place of collage and contrast, different eras, styles, colours and reference points strung together to create something new. At the more ornate end of the spectrum, jewellers such as SHAY and Bleue Burnham play with vibrant gems and pieces adorned with multiple stones. Like many of today’s jewellers, their pieces are intended to be layered together.

“As the boundaries of menswear and womenswear continue to blur, jewellery has undergone its own transformation”

When Sir Hardy bemoaned the standard advice given about men’s jewellery, he was implicitly critiquing a world of clothing that came with set categories and pressures. One of the more refreshing developments of the past few years is a move away from viewing fashion as a rulebook with a shifting set of dos and don’ts into something much more fluid – a question of expression over rigid expectation.

Jewellery is an intimate thing. We wear it close to the skin. We see it as the finishing touch to a look. We imbue it with meaning, sentimental or otherwise. How men can wear jewellery today is perhaps a reflection of masculinity as a whole – increasingly expansive. The dangerous ground Sir Hardy spoke of has already been trodden. Now we’re all walking it freely.

Run the jewels

The people featured in this story are not associated with and do not endorseMR PORTER or the products shown