THE JOURNAL

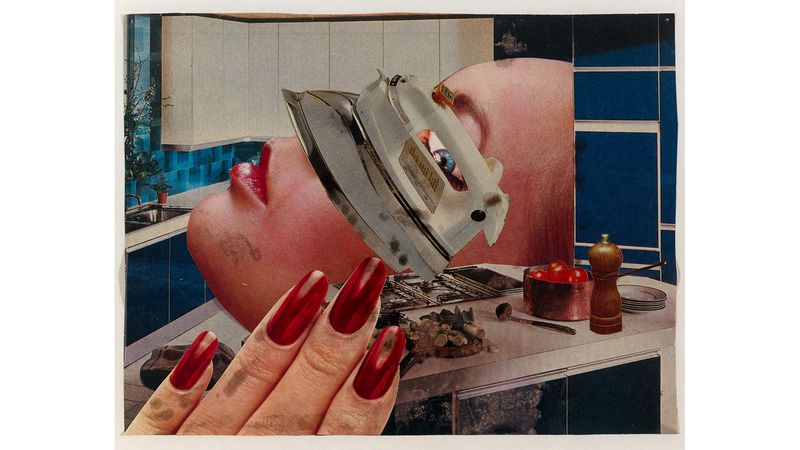

“Untitled” by Linder, 1977. Photograph courtesy of Mr Stuart Shave/Modern Art, London. © the artist

A new exhibition at The Design Museum in London explores visions for the way we live.

The home of the future is a popular sci-fi trope for the same reason that the digitised cityscape or flying vehicle is. It represents a familiar part of our lives, and yet provides endless opportunities to speculate how our daily existence might change in 30, 50 or 100 years. Consider the opening scene of 1968’s Barbarella. Besides Ms Jane Fonda sensuously removing her space costume, the viewer is also invited to observe the interiors of her space pod – walls covered in an ochre plush, video-phone, robotic operating system.

Imagining the home of the future was a popular idea among designers and architects in the middle of the last century. Take Ms Alison and Mr Peter Smithson’s 1956 “House Of The Future”, a model of a modernist home built around a courtyard that supplied all the natural light in lieu of windows, which had every appliance hidden in individual cabinets. But how close did they come to the reality of how we live now? That’s the question explored by a new exhibition entitled Home Futures, which opened yesterday at The Design Museum in London. Although mid-century modernism has enjoyed a revival of late as fashionable home decor inspiration, comparing the purposefully futuristic designs of the past century with contemporary innovation is equal parts interesting and amusing.

“Total Furnishing Unit” by Mr Joe Colombo, 1972. Photograph Mr Felix Speller for The Design Museum

The exhibition’s opening section, Live Smart, explores the modernist ideal of the “home as a machine”, comparing it to the contemporary vision of the “smart home”. A model of the Villa Arpel from Mr Jacques Tati’s 1958 film, My Uncle, is a tongue in cheek invitation to meditate on just how comfortable smart living actually is. In the film, the affluent owners of the Villa have completely sacrificed personal comfort for flashy, but inconvenient homeware: sofas made up of two affixed cylinders that are impossible to sit on, a kitchen filled with gadgets that hum at the decibel of a jet engine. It is at once a tongue-in cheek reminder of the forced aestheticism that sometimes defines the latest design trends (often at the expense of comfort) and the effect of the consumer striving to own the latest gadget.

In 2018, how we live is not merely an aesthetic question, but a political one. Around the world, housing shortages are becoming increasingly acute as urban overcrowding and rising property prices force the new generation of buyers and renters into smaller living solutions. Designs focusing on self-contained micro-living surfaced in the 20th century as a solution to the housing crisis, but have reappeared recently in cities such as Hong Kong and Taiwan, where the constantly expanding population is a continued strain on the housing economy. A model of Mr Joe Colombo’s 1972 “Total Furnishing Unit”, a multifunctional unit created for a variety of domestic needs (including beds, dining table and two body-sized individual chambers for “private retreat”) is shown in the exhibition’s Living With Less section, alongside Mr Gary Chang’s Domestic Transformer apartment in Hong Kong, a 344sq ft micro-flat that can be made into 24 different rooms through shifting walls.

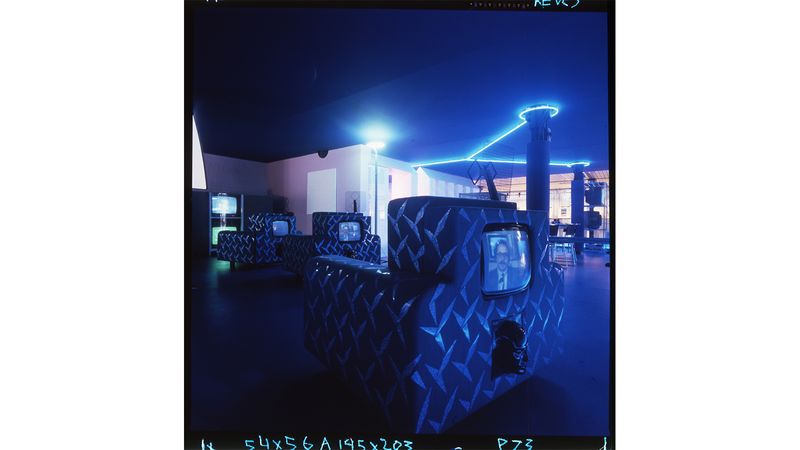

“La Casa Telematica” by Mr Ugo la Pietra, 1983. Courtesy Archivio Ugo La Pietra, Milano

If personal space is an important consideration, so is its invasion: the exhibition’s penultimate section, Living Together, looks at privacy in the home and negotiating technology in domestic spaces. Mr Ugo la Pietra’s “Telematic House”, a technicolour interior bathed in the light of screens and aggressively pointed surveillance cameras, first exhibited at the Milan Fair in 1983, invites the viewer to ponder how technology invades our lives. A pertinent consideration given that Amazon was reported to have sold more than 20 million Alexa Echo devices in 2017. While there is a clear demand for artificial intelligence-controlled home assistance, the technology is not yet without glitches – earlier this year, several Alexa users were left spooked by the device erupting in spontaneous, unprompted laughter.

Mr and Ms Smithson claimed that more than a model home, their “House Of The Future” was a simulation of how a married couple with no children might live, 20 years later. Windowless living never quite caught on, and perhaps neither will asking AI to switch off the lights or bulk-buy your toothpaste (without laughing). But the home, where technology meets domestic, daily life, remains a good place to look if you’re curious about the future.

**Home Futures runs until 24 March 2019 at The Design Museum **

Make yourself at home