THE JOURNAL

Mr Jock Whitney shot against the backdrop of the city, 1947 Arnold Newman/ Getty Images

The American author Mr O Henry, known for his witty stories of New York street life, once hailed the “Manhattan gentleman” for his “charming insolence, irritating completeness, sophisticated crassness and overbalanced poise”. He wrote those words more than a century ago, but their basic thrust – if you want to stand out in the US’ style hub, you have to try that bit harder while maintaining an air of breezy big-city nonchalance – is still germane today. The following individuals – you might call them the premier style corps of NYC – each carved their own sartorial slice out of the city and became menswear icons in the process. As Jay-Z, the modern Manhattan laureate, put it in “Empire State of Mind”: they “came here for school, graduated to the high life”. Let’s hear it for eight New York giants of style.

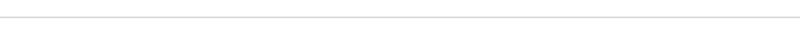

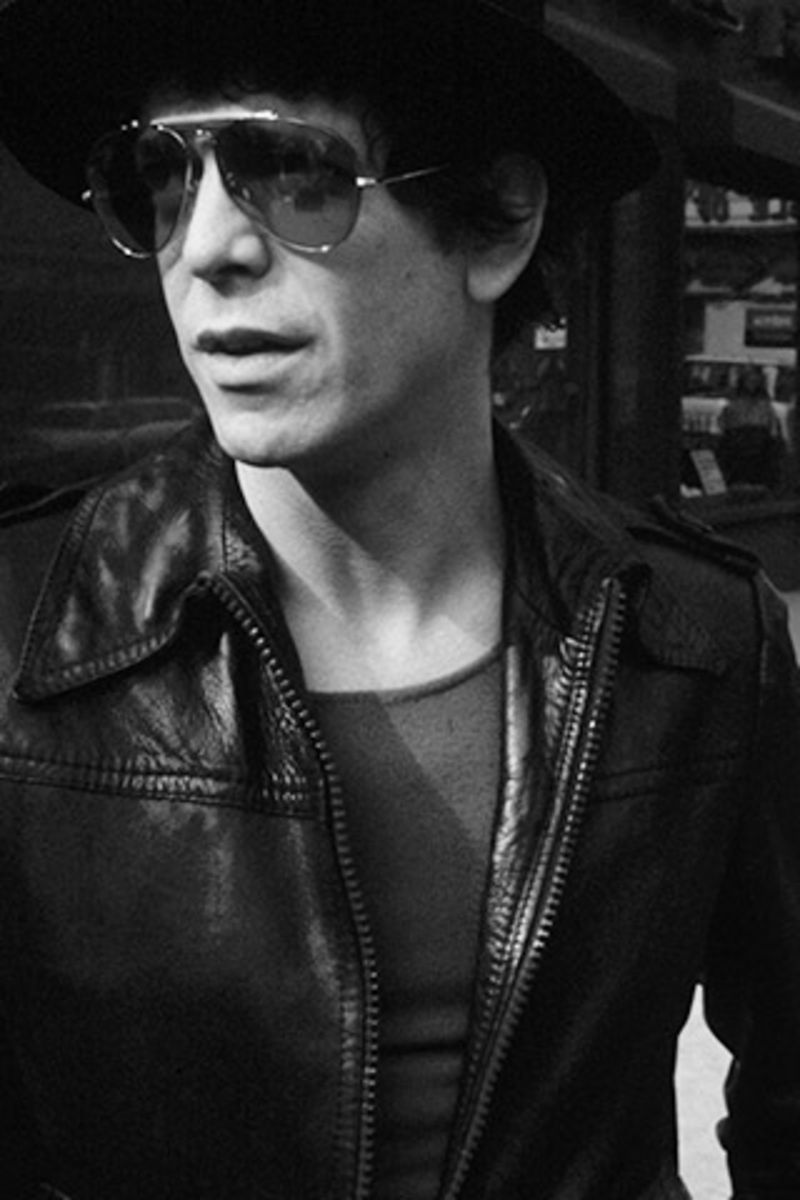

Mr Bob Dylan

Mr Dylan in his post-folk look, US, 1965 W Eugene Smith/ Magnum Photos

Long before Paris-based menswear designers were pushing peacoats and boot heels meant for wandering, a 1965 film clip from “Subterranean Homesick Blues” finds Mr Bob Dylan standing in a Manhattan alleyway, swapping his folky, flannel shirts for an electric combination of stovepipe jeans, waistcoats, polka-dot shirts buttoned up to the collar, soft-belted trenches, scarves, wayfarers, Cuban-heeled boots and a messy shock of hair. (“Have you ever noticed that Abraham Lincoln’s hair was much longer than John Wilkes Booth’s?” Mr Dylan once said, in defence of his unruly coif.) This was a look informed by Mr Dylan’s pilgrimage to Carnaby Street that same year, where he quick-studied the jingle-jangle mod style of the likes of Mr Eric Burdon of The Animals. There were many more incarnations of Mr Dylan to come, of course – the cowboy-hatted woodsy huntsman, the glam-rock preacher, the bolo-tied old-Western gentleman – because, as the man himself said: “All I can do is be me, whoever that is.”

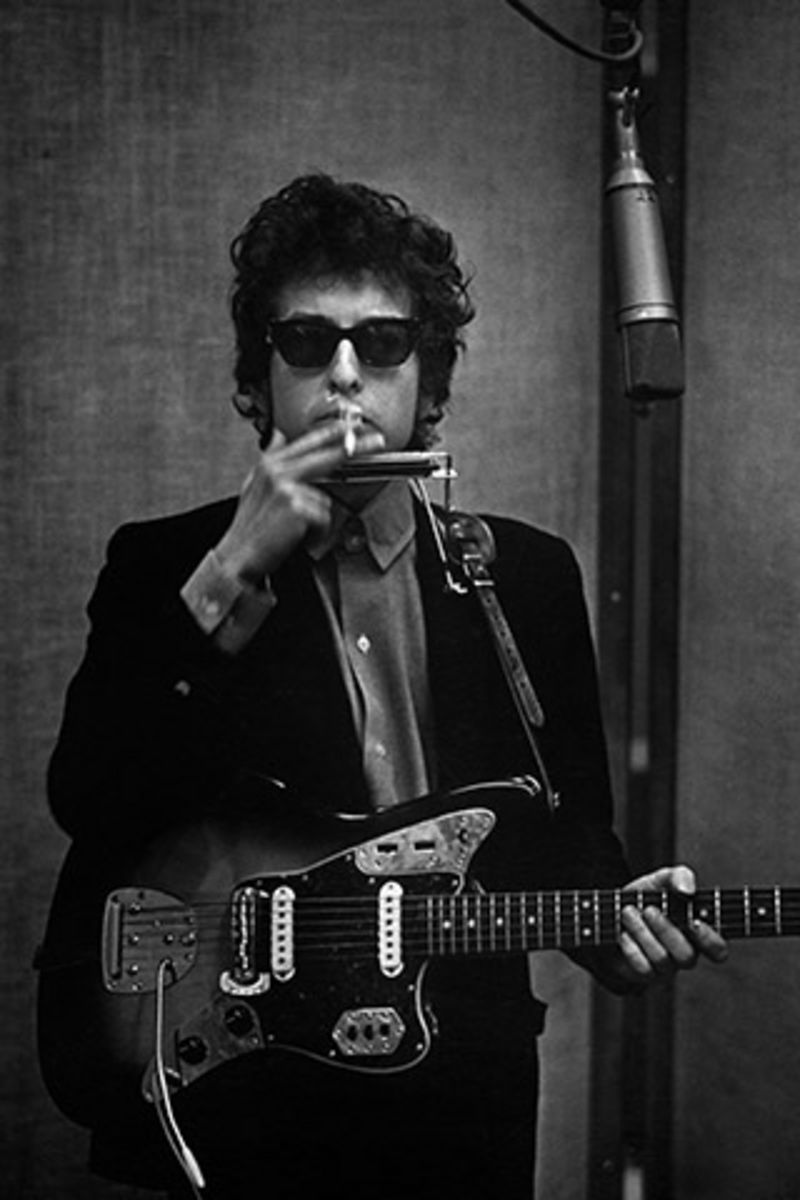

Run-D.M.C.

From left: Messrs McDaniels and Simmons in the outfits that took hip-hop to the masses, circa 1986 Brian Rasic/ Rex Features

“I wear my adidas when I rock the beat/ On stage front page every show I go/ It’s adidas on my feet high top or low.” In 1986, Messrs Joseph “Rev Run” Simmons, Darryl “D.M.C.” McDaniels and Jason “Jam Master Jay” Mizell set an enduring hip-hop/ clothing crossover trend in motion with “My adidas”, a fulsome tribute to the sportswear brand they favoured on their home turf of Hollis Avenue, Queens. They eschewed the flamboyant Funkadelic-meets-Lion King look of early hip-hop pioneers such as Melle Mel and Afrika Bambaataa for pared-down street smarts; unwashed straight-leg Levi’s 505s, black adidas tracksuits, gold “dookie rope” chains, black bucket hats and unlaced white adidas “shelltoe” Superstars with the tongues pushed up and out, allegedly in tribute to the “prison-yard style” sported by local inmates. That same year, “Walk this Way”, their breakthrough hit with Aerosmith, sent rap style into the mainstream. When Mr Angelo Anastasio, a senior adidas employee, saw tens of thousands of fans hoisting their sneakers aloft in Madison Square Gardens on the trio’s Raising Hell tour in 1986, the first hip-hop million-dollar endorsement deal was done, and a limited-edition Superstar sneaker produced (“Bum rush the stores”, went the ad slogan). The Run-D.M.C. range is still in production under the adidas Originals label, and the collaboration paved the way for a raft of joint ventures (Messrs Pharrell Williams and Kanye West among them), and today’s rash of sports luxe looks.

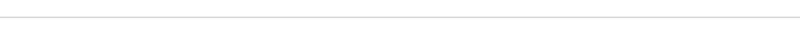

Mr Lou Reed

Mr Reed on the streets of New York, late 1970s The LIFE Picture Collection/ Getty Images

There’s a photograph of Messrs David Bowie, Iggy Pop and Lou Reed, taken by Mr Mick Rock in 1972. Mr Bowie is in his full cat-suited, androgynous pomp; the peroxided Iggy maintains his speed-freak grin with a pack of Lucky Strikes clamped between his teeth. Mr Reed is in his by-then-patented “couldn’t care less” mode, his saturnine bearing and oversized aviator shades offset by black nail polish and a floppy-collared blouson: a one-man awkward squad. “He was our generation’s New York poet, championing its misfits,” wrote Ms Patti Smith in a recent tribute. And Mr Reed elevated the ornery to an art form, whether hymning hedonism at the height of the Summer of Love, turning interviews into adversarial stand-offs, or ping-ponging gleefully between gossamer ballads and squalls of gnarly feedback. Style-wise, he also walked the iconic/ iconoclastic line, from the glam subversion of the Transformer album cover (panda guy-liner and a rhinestone-encrusted jacket) to transparent PVC jackets teamed with striped suspenders, to the bowler hat-tuxedo-printed-tee ensemble of the Coney Island Baby cover, a combination that no one’s had the audacity to attempt since. His ambivalent feelings about image are summed up in two lines from his classic “New York Telephone Conversation” – part leathery leer, part jaded ennui: “Oh my, and what shall we wear?/ Oh my, and who really cares?”

Mr John Hay “Jock” Whitney

Mr and Ms Whitney at Saratgoa Race Course, circa 1934 Bert Morgan/ Getty Images

On 27 March 1933, Mr Whitney graced the cover of TIME magazine. He was doing what any master of one of the great American fortunes (oil, real estate, tobacco) ought to be doing: pulling a pair of unfeasibly shiny riding boots over his immaculate polo whites, prior to a chukka or two at his 500-acre estate in Manhasset. A friend of Mr Whitney said that, for him, “money has three purposes: to be invested wisely, to do good with, and to live well off”, and as a sportsman, investor, publisher, philanthropist and political mover, he had a fair crack at the triumvirate. Mr Whitney was also known as a snappy dresser and has his own footnote in fashion history: while at Yale in the mid-1920s, he asked his local barber for a “Hindenburg” military cut to maximise his rowing performance. Because German words were still frowned upon in the aftermath of WWI, they gave it a new name, and the “crew cut” was born. Mr Whitney was also attuned to the finer things in life: he amassed a stellar art collection, including Rembrandts, Michelangelos, Picassos and Matisses, which hung on the walls of his Manhattan townhouse. In 1957, he achieved the career goal stated in his class book when he was appointed US Ambassador to Great Britain. In London, he trotted over to Savile Row, getting his suits – plus his celebrated equestrian ensembles – run up at Davies & Son.

Mr Andy Warhol

Mr Warhol photographed by Mr Elliott Erwitt, 1986 © Elliott Erwitt/ Magnum Photos

“In those days I didn’t have a real fashion look yet,” wrote Mr Warhol of the early 1960s, in his book POPism. “I just wore black stretch jeans, pointed black boots that were usually all splattered with paint and button-down Oxford-cloth shirts under a Wagner College sweatshirt.” Like all Mr Warhol’s utterances, this one should be delivered in a disingenuous drawl; after all, wasn’t this “look” just a refined version of that sported by his early downtown painter peers, Mr Jasper Johns and Mr Robert Rauschenberg? Mr Warhol, among his other gifts, was a master of sartorial osmosis; later in the decade we find him alternating between a summer “surfer look” of stripy Breton-style T-shirts (as pioneered by his then-muse, Ms Edie Sedgwick) and his “leather outfits from The Leather Man down in the Village” (also sported by his then-protégés The Velvet Underground). If Mr Warhol had a signature look of his own, it was that of the seriously skewed Madison Avenue advertising man. “Andy loved Brooks Brothers, and shopped there his whole life,” said his friend, the gallerist Mr Carlton Willers. “But he always looked bedraggled, with his tie lopsided and his shoelaces untied, and even different coloured socks. And he bought his first wig in the mid-1950s. If he liked something, he would buy a lot of them. It was all very self-conscious and calculating, and charming.” It also became the perfect visual shorthand for Mr Warhol’s “business artist” aesthetic.

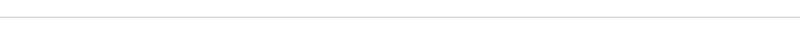

Mr Anderson Cooper

Mr Cooper arriving at the Late Show with David Letterman, 2014 Photo Splash News/ Corbis

There aren’t too many news anchors who have been photographed by Ms Diane Arbus as a baby for a Harpers Bazaar editorial, or who worked as a child model for Ralph Lauren, Calvin Klein and Macy’s, but then Mr Cooper is no ordinary news anchor. His mother is the writer, heiress and designer jeans pioneer Ms Gloria Vanderbilt; his father was the dapper writer Mr Wyatt Emory Cooper; and his maternal great-great-great-grandfather was the shipping/ railroad tycoon Mr Cornelius Vanderbilt. Mr Cooper hosts the CNN news show Anderson Cooper 360 from a New York studio and has also covered war-torn regions such as Somalia, Bosnia and Rwanda, but his personal style has attracted as much attention as his reporting; with his chiselled appearance and silver quiff making him the anti-Ron Burgundy. He was outed as a customer of Mr Ralph Lauren a few years ago by Mr Scott Schuman, aka The Sartorialist, who spotted Mr Cooper emerging from a changing room in a Black Label suit (he also favours the designer’s more relaxed Purple Label line). Mr Cooper likes what he calls “a good, thick shoe”, meaning Church’s brogues, and A.P.C. jeans. The news that he “rarely washes” his denims caused more of a stir than the pap-shots of Mr Cooper with his boyfriend, Mr Benjamin Maisani; but then, as Mr Cooper’s friend Ms Kathy Griffin recently said, “He doesn’t care what people say – he only cares about what people think he looks like.”

Mr Roy Halston Frowick

Mr Frowick across the pond, Paris, 1960 Jean Barthet

Mr Frowick dropped his fore-and-aft names when migrating from Iowa to New York in the 1960s; as Halston, he became America’s first “celebrity” designer, to the extent that his star on the Fashion Walk of Fame in Manhattan’s Garment District reads: “The 70s belonged to Halston”. By then, he’d established his elegant, minimalist womenswear label, and his status as premier “walker” for his A-list clients, including Mses Lauren Bacall, Elizabeth Taylor, Liza Minnelli, Martha Graham and Bianca Jagger. He hosted the latter’s legendary 30th birthday party at Studio 54, where she rode in on a white horse clad in a red Halston dress (Ms Jagger, that is, not the horse). His own style was equally classic and rigorous: he was always seen in impeccably-cut tuxedos, louche jackets in his trademark super-soft Ultrasuede fabric, smoky dark glasses (outdoors, and, especially, in), and, above all, immaculate turtlenecks. “They move with the body, and they’re flattering, too, because they accentuate the face and elongate the figure,” he opined. He held court at a Mr Paul Rudolph-designed bachelor pad on East 63rd Street, a vertically-held cigarette in one hand and a flute of champagne or tumbler of Scotch in the other, while offering a standard dinner of caviar, baked potato and narcotics. “Often,” says his biographer Mr Steven Gaines, distilling the era’s divine decadence in a single sentence, “the potato course was passed over.”

Mr Bill Cunningham

Mr Cunningham in his element, 2013 Dmitry Gudkov

When Mr Cunningham spots a fashion trend in the offing, the world pays attention. Why? For close to two decades – long before anyone had the tools to conceive of “street-style blogging” as “a thing” – Mr Cunningham, now 85, has been patrolling New York’s canyons (the four corners of 5th Avenue and 57th Street are his nerve centre) astride his trusty Schwinn bicycle (he’s on his 29th) with a battered Nikon, recording every look that takes his fancy for his On the Street column in The New York Times. “We all get dressed for Bill,” said Ms Anna Wintour in the recent documentary Bill Cunningham New York, while Mr Cunningham put it more pithily: “I’m just after someone who doesn’t look like they were stamped out of 10 other people looking all the same.” That includes male subjects as well as female; indeed, Mr Cunningham is perfectly placed to document every nuance of what he calls “the snail’s-pace changes in men’s fashion”. Historical columns have featured men in skirts, the rise of the “bearded lumberjack”, and, most recently, “the first platoon of a new peacock revolution”. Mr Cunningham’s own ascetic style has remained unchanged for decades: he wears a blue multi-pocketed workwear smock, bought in bulk from a Paris bazaar (“the ones the street-sweepers wear”, he says, proudly), with a backward tweed newsboy cap over his white hair, a messenger bag for his rolls of film and a plastic poncho for the rain (which he patches with gaffer tape).

None of the celebrities featured endorse the products shown