THE JOURNAL

The father-son bond is the unshakeable foundation of the motorbiking world. The vast majority of riders’ first experiences on two wheels come courtesy of their fathers, many of whom will have been racers themselves, a fact that should hardly come as a surprise when you consider the sport’s exceptionally high barriers to entry. The inherent risk, the prohibitive cost and the sheer technical complexity mean that it’s difficult to get started, let alone to succeed, without the experience of previous generations to lead the way.

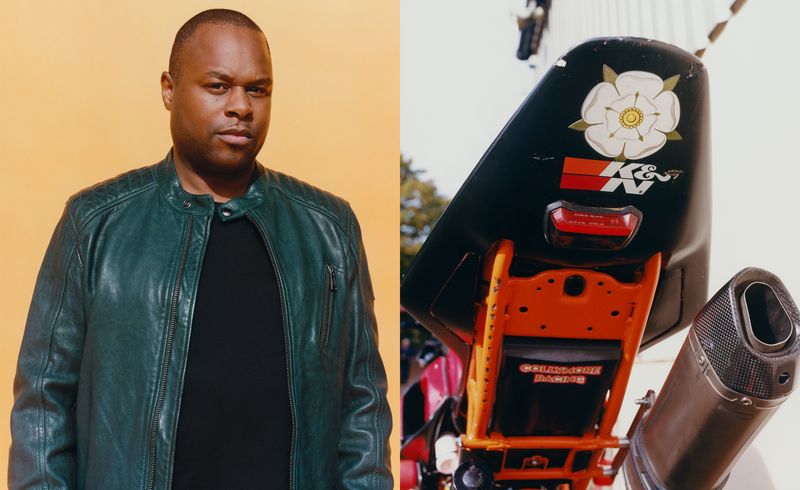

On the face of it, the Collymore family – Yorkshire-born sons Chace, 15, and Taio, 13, and Londoner dad Barry – are the archetypal motorbike racing family. But first impressions rarely tell the whole story, and there’s more to them than meets the eye. “I’m actually the odd one out in the family,” admits Barry. “I was never a racer.” A keen rider in his youth, his personal ownership history reads like a fantasy superbike wishlist dated circa 2005: Honda FireBlade, Kawasaki Ninja, Yamaha R1. But a high-speed accident on a motorway 16 years ago, just before he became a father to Chace, put him off and he hasn’t been back on a bike since.

Instead, you have to go back another generation, to Chace and Taio’s grandfather on their mother’s side, Gary, to explain how they managed to establish themselves as two of the hottest young prospects on the British road racing scene. Gary is a man you could describe as a racer manqué; the driving force behind Collymore Racing, he fell in love with trial bikes as a youngster – “I loved the noise, the smell, everything,” he explains in a thick Yorkshire accent – but was forbidden from riding them by his mother.

It wasn’t until his early 30s that he finally got serious about track racing, but by then any shot at the big time had passed. “I wasn't very good,” he laughs. “Had a lot of fun though. Spent a lot of money.” When his grandchildren were born he poured his passions into them, introducing Chace and then Taio to minibikes before transitioning them onto bigger bikes and eventually giving up on his own riding in order to focus fully on their fledgling careers. “I’d have killed to have had the chance they’ve had,” he says. “I’d have been world champion!”

This might sound like a candid admission from Gary, who describes himself with a wry, self-deprecating humour as a “failed wannabe racer”, but there's really nothing unusual about men like him, who see in their children and grandchildren a second chance for their own missed opportunities and unrealised ambitions. Whether it’s an engraved pewter hipflask, a beaten-up leather jacket or a favourite pastime, it’s in our nature to pass things on. This goes some way to explaining the dynastic nature of motorbike racing, where sons follow in their fathers’ footsteps and uncles and grandfathers can often be found helping out in the pits. It lends the sport an air of history and tradition that can feel strangely at odds with its reliance on hi-tech engineering – but in truth it’s this marriage of old and new, of tradition and innovation, that defines motorsports.

It’s why Belstaff feels so at home here, too. The British brand, founded in 1924 by Mr Eli Belovitch and his son-in-law, Harry Grosberg, made its name in the early 20th century designing protective clothing for motorcyclists, along with camping, fishing and other outdoor pursuits. Some of its earliest models, such as the Trialmaster waxed-cotton jacket designed for legendary Trials biker Mr Sammy Miller to tackle the Scottish Six Days Trial in 1948, are still in production today.

But where other heritage brands might get stuck in a rut, Belstaff calls on its history of innovation to inform a new direction of travel. That’s why, alongside the brand’s classic lineup of future-heirloom biker jackets in its trademark waxed cotton and leather, you’ll also find 21st-century style staples such as quilted gilets made with Gore-TexTM and other technical materials and packed with responsibly sourced down.

While Belstaff’s heritage as a motorsports outfitter illustrates how certain things never go out of style, it also acts as a reminder of just how far the competitive biking scene has come – both in aesthetic and technical terms. The suits worn by racers today bear little resemblance to the belted leather jackets that riders in the mid-20th century wore for protection, and it’s not just the vivid colours and sponsorship logos adorning modern race suits that set them apart. There are a raft of additional safety features on modern suits, too – features that only become more important as motorbike racing gets faster.

The inherent dangers of motorbike racing are never far from Barry’s mind. His own brush with death on a motorway 16 years ago is a constant reminder of the risks his sons endure every time they straddle a bike. But it’s far from the only one. With grim timing, the Collymore family are sitting for photos just two weeks after the death of 26-year-old British superbike rider Mr Chrissy Stouse at Donington Speedway, and less than a week after the death of 22-year-old Dutch rider Mr Victor Steeman in the Portuguese leg of the World Supersport 300 – a double tragedy that shocked the sport.

Steeman’s death was particularly close to home for the brothers, who compete in a similar classification – and ride similar bikes – in their own NG Road Racing championship series. Indeed, the modified KTM 390 that Taio rides is the same model that Steeman rode for three seasons. So, is the risk worth it for the opportunity? Barry remains philosophical. “Of course I want them to be safe,” he says. “But I want them to be happy, too. It’s not easy to get established in anything these days, so giving them the chance to find their passion and go far with it, that’s all I ask for.”

But while early opportunity is proving beneficial to these young riders – Chace, in particular, is showing a proficiency for the sport that could take him far – there is more to this lifestyle than chasing trophies and podium places. What inspires the Collymore family, and so many others like them, to spend their weekends criss-crossing the country crammed into a van? To endure the risks and shoulder the expenses? You only need to look at them together to see. It’s kinship – between brothers, between generations – and that unquenchable desire to keep traditions alive.