THE JOURNAL

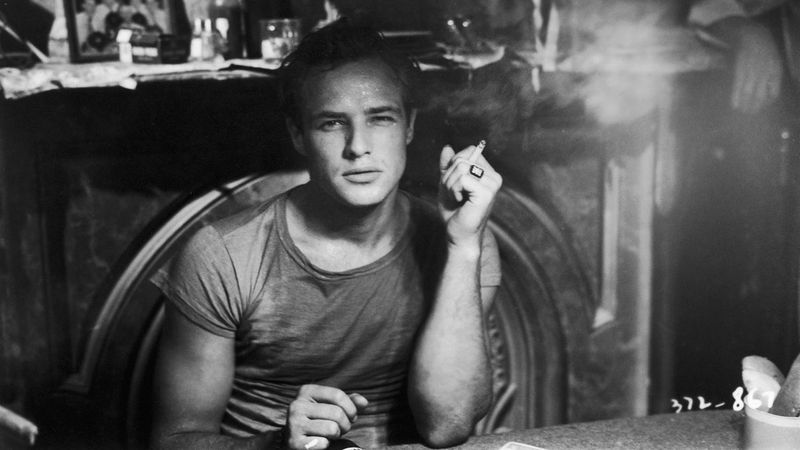

Mr Brando in a film still from A Streetcar Named Desire, 1951 Alamy

Thanks to a new, groundbreaking documentary, the last word on Mr Marlon Brando will be had by the man himself .

Mr Marlon Brando was one of the 20th-century’s foremost cultural icons, a brilliant yet troubled man who remains an endless source of fascination more than a decade on from his death. As an actor, he was possessed of perhaps the greatest natural talent of his generation – a talent that shone brightly in films such as On the Waterfront, but was diluted by numerous cinematic failures. Off-screen, he was just as unpredictable: he shunned the limelight, scorned the cult of celebrity and was often openly contemptuous of Hollywood. His reputation as a difficult and demanding actor was hardly enhanced by his almost total refusal to give interviews, and his terse, defensive manner on the few occasions that he did.

Born in 1924 in Omaha, Nebraska, the third child of Mr Marlon Brando Sr and his wife Dorothy, Mr Brando’s Midwestern upbringing must have looked to an outsider like a classic vignette of the American Dream. But beneath the glossy, oil-painting surface, there were cracks. His father was domineering and abusive, his mother an alcoholic. They were separated by the time he was 11. After being expelled from military academy at the age of 18 he decided to follow his two older sisters to New York to study acting at the New School, where he was greatly influenced by his teacher, Ms Stella Adler. Her instruction of “Method” acting was instrumental to Mr Brando’s early success as an actor, first as the brooding Stanley Kowalski in A Streetcar Named Desire and then later in his Oscar-winning turn in On the Waterfront.

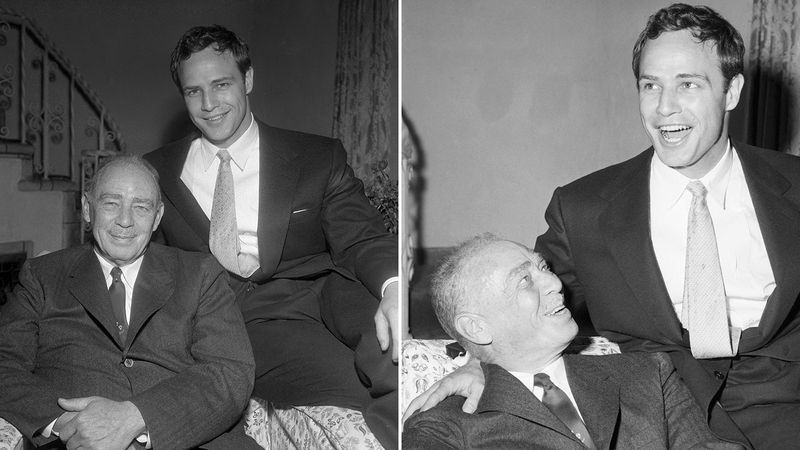

A young Mr Brando with his mother, 1933 Brando Estate

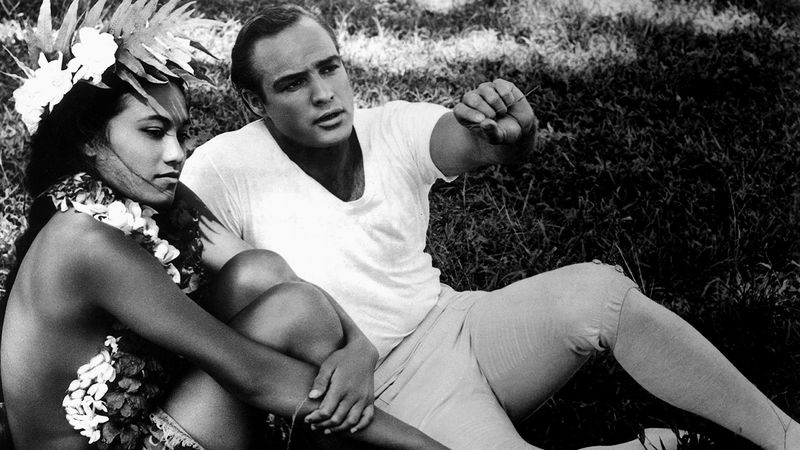

By the late 1950s Mr Brando was a bona fide superstar, but he was beginning to fall out of love with Hollywood – and Hollywood was beginning to fall out of love with him. It was during the fraught production of 1962’s Mutiny on the Bounty, which he was accused by directors and studio executives of having deliberately sabotaged, that his reputation finally went into free-fall. But it was also during this production that he first visited Tahiti, the island that he would eventually call home, and where he met his third and final wife, Ms Tarita Teriipaia. While his career would flash briefly back into life in 1972 with roles in Last Tango in Paris and The Godfather – the latter of which would bring him his second Oscar – he would never again manage to scale the heights of his early performances.

Ms Teriipaia and Mr Brando in Mutiny on the Bounty, 1962 Alamy

Towards the end of his life he retired to the shadows and seldom acted, becoming a bloated, cartoonish version of his former self. By now, his legacy was in serious danger of being eclipsed both by the scandal surrounding his chaotic family life – he had fathered at least 11 children, one of whom, Mr Christian Brando, murdered his half-sister’s boyfriend at the family home on Mulholland Drive in LA – and by his ever-expanding waistline, which was such an unseemly sight on a man whose chiseled beauty had once forced audiences to reconsider their very definition of masculinity. When he died in 2004 from respiratory failure at the age of 80, obituarists wrote of a larger-than-life character who charted new emotional territory as an actor and yet never managed to overcome his own personal demons. Perhaps the word they reached for most was “enigma”, for he left a great deal of mystery in his wake: it seemed as if the only person who ever truly knew Mr Marlon Brando was the man himself.

Now, 11 years after his death, he will finally have the chance to tell his own story. In Listen to Me Marlon, a new biopic from Passion Pictures, director Mr Stevan Riley has been given exclusive access to Mr Brando’s personal archives, including hundreds of hours of private audio recordings, which he wove into a narrative that is delivered entirely by the man himself. This is Brando on Brando: a one-of-a-kind documentary, and surely the final word on one of the greatest actors of the 20th century.

The actor at his Hollywood home with his father, 1955 CBS via Getty Images; Corbis

As Mr Riley explains, the unconventional decision to tell the story exclusively from Mr Brando’s point of view was not made lightly. “It’s hard to portray how terrified I was,” he says. “When we chose to go in this direction, all we’d received from the Brando Estate were a few tapes. There was the promise of more to come, but it wasn’t until about three or four months into production that we received them all. By then, we were well beyond the point of no return.” The creative decision was made by Mr Riley along with Mr John Battsek, veteran producer at Passion Pictures, with whom he has worked on two previous projects: _Fire in Babylo_n, a documentary about the West Indian cricket team in the 1970s and 1980s, and Everything or Nothing, which tells the story of the Bond movie franchise. It was Mr Battsek who was approached by the Brando Archive in the first place to create the film, having previously worked with them on a movie called We Live in Public. “It was a bold thing to do,” he says. “We were spending production dollars having committed ourselves to telling the story in this specific way, and you don’t get to the point you’re sure that it’s going to work until way, way down the line. It was always in the back of my mind that at any point either of our financiers could have said, you know what, we need an interview with Jack Nicholson. And it just wouldn’t have worked. You couldn’t break that spell.”

Mr Brando at the Paramount Studio commissary, 1955 MPTV

But the results show that the film-makers were vindicated in sticking to their original plan. Mr Brando speaks incredibly candidly on tape, laying himself bare in a way that he never did in interviews when he was alive. While many of his recordings were made in preparation for acting roles, others were intended solely as a form of therapy. In fact, the movie’s title is taken from one of several tapes in which he attempted self-hypnosis. “Listen to me, Marlon,” he intones. “This is one part of yourself speaking to another part of yourself. Listen to the sound of my voice and trust me. You know I have your interests at heart.” These recordings reveal a man who was entirely at odds with the world around him – “a troubled man,” as he put it, “alone, beset with memories, in a state of confusion, sadness, isolation, disorder.”

And it appears that one of the main sources of disorder in his life was his tumultuous love affair with acting itself. On the one hand, he spoke with great passion of his desire to change acting and to bring it closer to “the truth”. In which he succeeded: through his application of Method acting, he was arguably the first man to appear on screen without a mask – the first to show real vulnerability and genuine, unfettered emotion – and his groundbreaking acting style can be seen echoed in the work of men such as Messrs Robert De Niro, Al Pacino, Dustin Hoffman and countless others. On the other, he expressed a deep distrust for acting, calling it “lying for a living”. According to Mr Riley, though, “what he didn’t like was the politics of acting. The business end. He’d get deeply upset with the industry, and he’d often feel as if he’d been hard done by. But he was still very meticulous when it came to the process itself, preparing thoroughly for every role. The craft was what he loved.”

The Men starred Mr Brando as a paralysed war vet trying to adjust to the world, 1950 Corbis

While Mr Brando’s extraordinary career provides the film with a linear narrative, both director and producer are keen to point out that Listen to Me Marlon is not, ultimately, a documentary about Marlon Brando, the iconic actor – but rather about Marlon Brando, the Everyman. “I think that what revealed itself through telling the story from his perspective, and one of the reasons that the film has struck such a nerve with those who have seen it, is that on a certain level, he could be any one of us,” says Mr Battsek. “We’ve all struggled with what he struggled with, be it money, weight, family or love. And if we’ve achieved one thing with this movie, I hope it’s to have made Brando somebody who we can all relate to.”

Of course, the irony is that while the obituarists may have been right in labelling him an “enigma”, when he was in front of a camera or up on stage Mr Brando was was perhaps the most relatable actor of his generation, blessed with a rare ability to conjure up characters in whom we could all catch a glimmer of ourselves – characters to whom we could all connect. As he put it himself, referring to perhaps his greatest performance as Terry Malloy in On the Waterfront, “everybody feels like they’re a failure. Everybody feels like they could’a been a contender”. That is the sad truth revealed by Listen to Me Marlon: here was a man who was never able to connect with the world in the way that the world was able to connect with him.

Listen to Me Marlon is released in the US on 29 July and the rest of the world on 28 October