THE JOURNAL

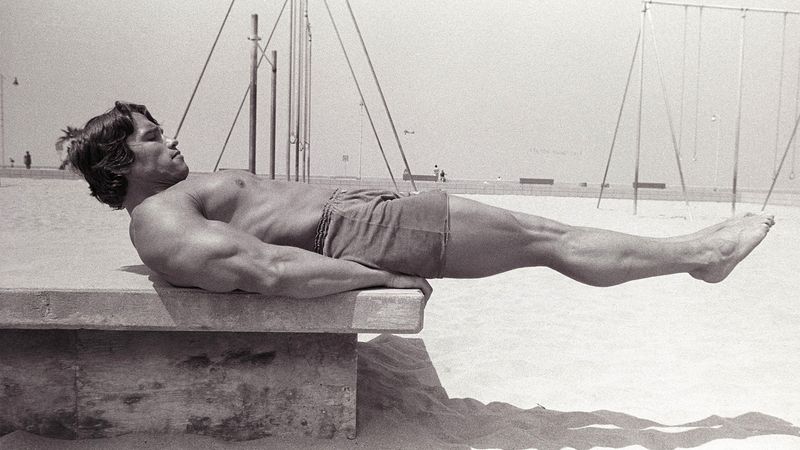

Mr Arnold Schwarzenegger at Muscle Beach, Los Angeles, 6 July 1979. Photograph by Mr Douglas Kent Hall/Zuma Press

I have photos of me enjoying skin-to-skin contact with my two daughters when they were born – some of the happiest moments in my life. But when I look back at the images, my overriding thought is: I’m so skinny. Even in 2014, when I completed a staff transformation challenge for the UK edition of Men’s Health magazine and my naked torso adorned newsagent shelves nationwide (and the Daily Mail “sidebar of shame”), I wasn’t completely happy with my body. I could’ve done better. Been bigger.

While my experience may be unusual, I’m not alone in my body dissatisfaction. A survey earlier this year by UK suicide prevention charity the Campaign Against Living Miserably and Instagram found that nearly half of men aged 16-40 have struggled with their mental health because of how they thought about their bodies. More than half said how they thought about their bodies had been worsened by the pandemic. A 2019 survey by UK charity the Mental Health Foundation found that 28 per cent of men aged 18 and above had felt anxious about how their bodies looked while 11 per cent had felt suicidal.

Men aged under 18 – or boys, more accurately – are not immune to this negative body image epidemic. The 2020 Good Childhood Report by young people’s charity the Children’s Society recorded a “significant decrease” in boys’ happiness with their appearance. In Australia, dissatisfaction with muscularity has been reported in boys as young as six.

The problem has been growing since the second half of last century. In a series of surveys by US magazine Psychology Today, the 15 per cent of men dissatisfied with their bodies in 1979 nearly tripled in fewer than 30 years to 43 per cent in 1997. To highlight the “secret crisis”, a group of leading researchers coined the term “the Adonis complex” in a seminal book of the same name published in 2000 – that is, before social media.

Over two millennia before Photoshop or filters, Greek sculptors adjusted the proportions of their statues beyond the natural limits of human anatomy to appear more balanced, or heroic. Whoever sculpted the famous Farnese Hercules, a Roman copy of a lost Greek original, would have never seen a flesh-and-blood man who measured up to the marble-carved demigod who, in turn, wouldn’t have a hope in Hades of winning the Mr Olympia bodybuilding contest today. Because the advent in the 20th century of anabolic-androgenic steroids (“anabolic” as in muscle-building and fat-burning, “androgenic” as in masculinising – think deep voice and facial hair) has enabled humans to transgress those natural limits with Promethean hubris.

Testosterone, nature’s own steroid, was synthesised in 1935 and followed by myriad synthetic variations that infiltrated bodybuilding and weightlifting in the 1940s and 1950s, then other sports. The 1990s saw the big-hitting “steroid era” in Major League Baseball and bans for high-profile footballers such as Messrs Frank de Boer, Edgar Davids, Jaap Stam and Pep Guardiola (who was later exonerated by a court) after testing positive for steroid du jour nandrolone. And steroids, which don’t just build muscle but also boost recovery, are merely the most widely known and abused of an ever-expanding pharmacopoeia of image and performance-enhancing drugs (IPEDs).

“In the 1980s, steroids pervaded advertising, which capitalised on the crossover appeal of the muscular male torso to market to women and increasingly to men, gay and straight”

Sporadic doping scandals – or in the case of cycling, perpetual – don’t tell the whole story. Six of the 11,656 athletes at Tokyo 2020 have, at the time of writing, produced “adverse analytical findings”, the 624 footballers at Euro 2020 none. But as former World Anti-Doping Agency president Mr Dick Pound told a British tabloid in 2018, following the revelation that 11 Premier League footballers had secretly tested positive for performance-enhancing drugs in recent seasons but allowed to play on, the lack of positive tests in the world’s largest sport is “a matter of suspicion in its own right”. Most sports chiefs, he said, don’t want positive tests and the resulting negative publicity.

In the 1980s, steroids pervaded advertising, which capitalised on the crossover appeal of the muscular male torso to market to women and increasingly to men, gay and straight. And steroids went to Hollywood, most prominently via Mr Arnold Schwarzenegger, who has since admitted his abuse and spoken out against the drugs. But his physical peak is still a byword for the apotheosis of the male form. Today’s cinematic action heroes don’t even need to abuse steroids and other IPEDs, though some undoubtedly do: their bodies can be covertly tweaked, transformed or entirely transplanted by CGI.

The number of steroid abusers is estimated (likely conservatively) at over a million in the UK, and tens of millions worldwide. About 98 per cent are male. And they’re not all enormous bodybuilders or elite athletes; they’re mainstream gym-goers and grassroots sportsmen. The most common type of steroid abuser is a thirtysomething white-collar professional, I was told by University of Melbourne researcher Dr Scott Griffiths, who describes rising steroid abuse as “the canary in the coal mine” for soaring male body dissatisfaction.

It has been theorised that men are evolutionarily hardwired to venerate muscles, which may signal the ability to provide and protect. But if that were the whole story then the drive for muscularity would be universal and constant, which it’s not. When I asked Duke University evolutionary anthropologist Dr Herman Pontzer, author of the recent book Burn: The Misunderstood Science Of Metabolism, about this “survival of the muscliest” hypothesis, he dismissed it as “self-serving bro-science bullshit”.

Instead, the drive for muscularity is predominantly culturally programmed: by films, TV, newspapers, magazines, comic books, action figures with proportions that can’t be achieved even with steroids, porn. Any slight inbuilt preference for muscles is exaggerated out of all proportion by culture, insecurities weaponised by the burgeoning male body image-industrial complex to sell a battery of products. And that’s just one manifestation of a culture obsessed with youth and beauty, performance and productivity. Muscularity is equated with masculinity and traditional Western cultural notions thereof: strength, power, efficacy, dominance.

It’s in Western, Educated, Industrialised, Rich and Democratic (WEIRD) countries where men now least need but most want muscles. One theory for why is that women’s advancement into the workplace and the disappearance of traditionally male-dominated industries has triggered a “crisis of masculinity” amid which muscles are one of the dwindling number of ways for men to demarcate themselves as such and forge self-worth. I live in the northeast of England, a former industrial heartland that has a steroid abuse rate among the highest in the UK.

Steroids don’t just harm those men and boys who abuse them and suffer dire consequences both physical (heart disease, toxicity of other organs and persistent hypogonadism, or low-to-no testosterone and sperm production) and psychological (ranging from common “roid rage” to, more rarely, full-blown mania, depression and suicide). Steroids also indirectly harm those exposed to the unnaturally muscular body ideals they produce, and to which males in WEIRD countries are most exposed.

“Social media, use of which has been linked to increased drive for muscularity in men and boys, has only amplified and made more targeted the bombardment”

Social media, use of which has been linked to increased drive for muscularity in men and boys, has only amplified and made more targeted the bombardment. Expressing a liking for fitspo content can send you tumbling down a rabbit hole of extraordinary physiques, many of them enhanced chemically or digitally and misleadlingly promoting workout programmes and supplements that purport to deliver the same results – the latest update of a time-honoured fitness industry bait-and-switch. Research shows that even knowing an image is fake doesn’t prevent you feeling bad about yourself by comparison.

It’s important to note that some men and boys – such as those with low self-esteem or a tendency to compare themselves with others – are more susceptible to these hypermuscular ideals. Other individual factors in the drive for muscularity include perfectionism, parental or peer pressure and being bullied verbally (particularly about appearance) or physically. But a constant barrage of muscular male bodies, enhanced or otherwise, doesn’t help anybody.

Building muscle, like losing weight, is healthy, desirable even, in the right context. But building muscle is less likely to be recognised as unhealthy by, say, the parents of a teenage son (thanks also to gender stereotypes), even though it can be just as dangerous if taken to extremes. Muscle dysmorphia, aka “reverse anorexia” or “bigorexia”, is the pathological preoccupation that you’re not muscular enough, however big or lean you may objectively be. Like anorexia, it can be a maladaptive coping mechanism, a way to gain a sense of control at times of stress or in response to trauma.

Muscle dysmorphia is, like steroid abuse, hard to quantify but getting bigger. And as Harvard clinical psychologist Dr Roberto Olivardia, who coined the term (and contributed to The Adonis Complex), explained to me, muscle dysmorphia exists on the end of a spectrum of subclinical but still harmful behaviour. The extent of body distortions (seeing yourself as small when you’re clearly not), body image dictating self-esteem, pursuing muscularity to the detriment of normal life and compulsively exercising are all diagnostic red flags; treatment includes cognitive behavioural therapy and certain antidepressants. On the less severe end, Griffiths prescribes celebrating your body for function for form. (Just be mindful you don’t fixate on performance, either.)

Men and boys need to learn, as women and girls have, to be more critical of the body ideals we’re subjected to and spreading, and to voice our concerns. Not everybody who’s in great shape is abusing steroids, but then again not everybody who’s abusing steroids is in great shape. And there undoubtedly needs to be greater acknowledgement of the suspiciously large, well-defined elephant in the room, and of the natural limits, which are lower than we’ve been conditioned to think by unknowing exposure to chemically enhanced bodies.

Maybe that physique has been enhanced chemically, digitally or by a flattering camera angle, lighting and, if any, clothing. Or maybe it really is a product of time, effort and favourable genetics. (I find myself going down the rabbit hole of r/nattyorjuice, as in “natural”, which is to say “not on drugs”.) Either way, it’s perhaps even more important to ask: is comparing your body to others realistic? Fair? Necessary? And who does that comparison really serve?