THE JOURNAL

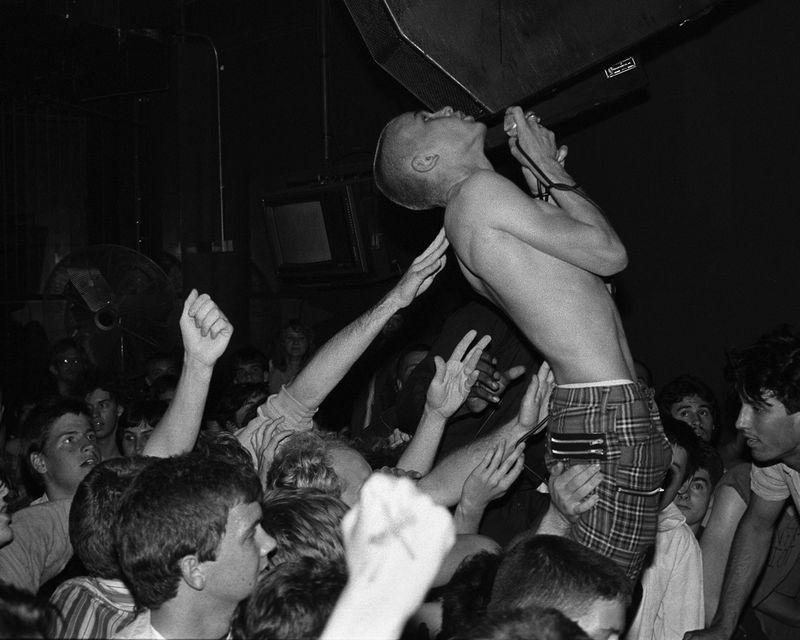

Mr Alec MacKaye, brother of Mr Ian MacKaye, on stage with The Faith at The 9:30 Club, Washington DC, 23 June 1983. Photograph by Mr Jim Saah

“Straight Edge”, the fourth track on the debut EP by the Washington DC hardcore punk band Minor Threat, is all over in just 46 seconds. But the song has had a lasting legacy. Spat out by frontman Mr Ian MacKaye, its anti-drugs lyrics – I’m a person just like you / But I’ve got better things to do / Than sit around and fuck my head / Hang out with the living dead – stood as guiding principles for a movement that just over 40 years later is still relevant and referenced. So how did an extreme punk track, released on an independent label in 1981 with barely decipherable lyrics and little or no promotion, end up having such a huge impact? And what was, and is, straight edge?

In basic terms, straight edge is a subset of punk that espouses clean living. While adherence varies among individuals, it shuns alcohol, drugs and cigarettes and, in some cases, casual sex. There is a frequently anti-capitalist edge to it and bands opt out of the usual hoopla of promotion, press and merchandise. Veganism and progressive politics can also be in the mix, but are not a given. There is a large crossover with the skate scene.

A common identifier of straight edgers is an “X” on the back of the hand, a reference to the mark once applied to underage gig-goers to stop them getting served at the bar. (In 2010, Metallica’s Mr James Hetfield marked his newly embraced sobriety with a tattoo on his right wrist of a pair of cut-throat razors in an X formation, telling Metallica fanzine So What! that “I’m a reborn straight edge”.)

Despite a tendency to humourless puritanism, the straight edge scene is responsible for some of the most thrilling recordings to have emerged from the global punk scene. It’s a hard heart that can hear Youth Of Today’s Break Down The Walls and not get a strong sense of just how militantly exciting this music sounded when it was first released.

“Straight edge’s continued appeal lies in its ability to give people a solid set of principles to live their lives by at a time when spiritual and political meaning is lacking”

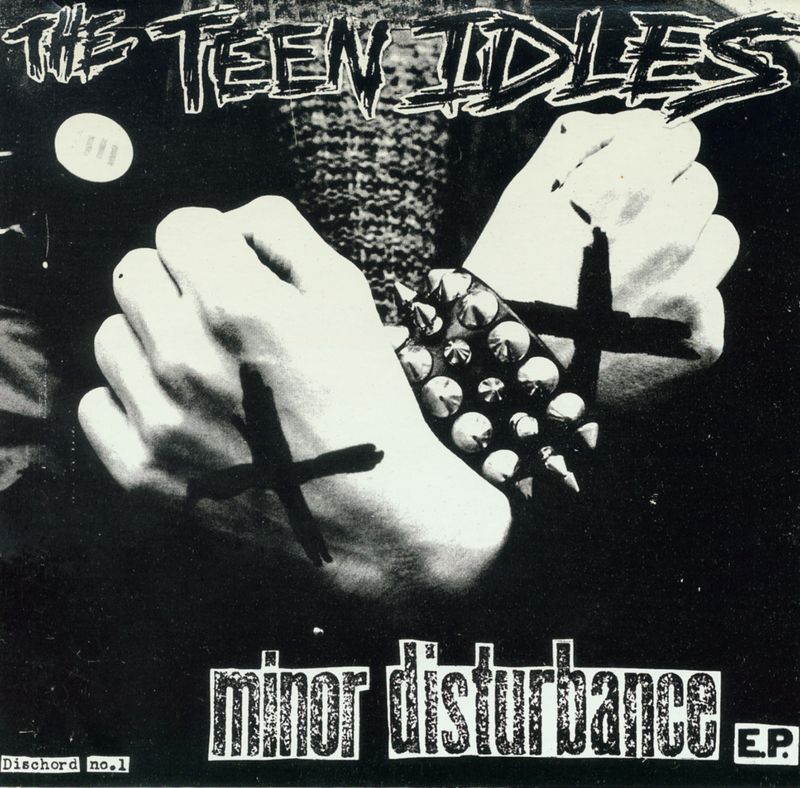

By 1980, the first wave of punk had flamed out in a mess of hard drugs, violence and self-defeating nihilism. Mr Sid Vicious of the Sex Pistols, The Germs’ Mr Darby Crash, The Ruts’ Mr Malcolm Owen and The Dickies’ Mr Chuck Wagon were all dead, with heroin a common denominator within the scene. Perhaps tellingly, the back cover of Minor Threat’s first release features an illustration of an alcoholic punk, with a bottleneck for a head, wearing a studded leather jacket and a Sex Pistols T-shirt.

“It’s a reactionary stance against the indulgent cultures that preceded US hardcore,” says Mr Stevie Chick, the journalist and author of several books on the US hardcore scene, including the acclaimed Spray Paint The Walls: The Story Of Black Flag. “As far as I understand it, [MacKaye] looked at these preceding rock cultures and disdained the wastage of it all, the needless death and misery and also the way drug abuse made generations politically immobile and vague and unable to enact change.”

This new mindset wasn’t just reflected in a sound that was faster, harder and more abrasive. The style was adopted by its adherents. Leather, studs and mohawks were gone, replaced by plain jeans or khakis, cropped or shaved heads, T-shirts and functional footwear. There’s an element of straight edge that made its adherents look like college jocks gone slightly off the rails. The scene’s look subverted elements of sporting life and military recruitment into something counter-cultural.

The Teen Idles, “Minor Disturbance EP”, 1980. Photograph courtesy of Dischord Records

Minor Threat arrived loud and burned out fast. After just two short albums’ worth of material, they split in 1983, disillusioned with the scene (Salad Days, released post-split, struck a rueful note). MacKaye pushed his musical career into increasingly complex directions with Fugazi, while still adhering to the values of independence and purity that his original band had defined.

“To MacKaye’s credit, swiftly after straight edge became a thing, he was quick to try and portray himself in less of a stentorian, authoritarian position,” says Chick. “It wasn’t a credo others should live by, but his own belief. He moved a lot of misplaced energy [in the scene] in a positive direction.”

While MacKaye’s ethos became more nuanced and personal, the fire ignited by his band continued to burn over the following decades. On the West Coast, Uniform Choice went fast and hard. Youth Of Today and the “Youth Crew” circuit thrived in New York in the mid-1980s, cultivating a more confrontational, knuckleheaded scene. By the decade’s end, releases such as Judge’s “In My Way” had become more preachy about straight edge. In the 1990s and beyond, bands such as Earth Crisis grafted straight edge onto militant environmentalism. Whenever the mainstream co-opted alternative culture, straight edge remained as a last redoubt of real independence – financially, spiritually and creatively.

Straight edge has culturally endured as a shorthand for a classic kind of rough-edged, independent-minded Americana. American Apparel drew heavily on the aesthetic and the Vans brand is rooted in a dream of that time. In 2005, Nike had to row back after appropriating the Minor Threat brand for a skate tour. In 2009 Forever 21 sold bootleg Minor Threat T-shirts. In 2013, legitimate editions finally appeared in Urban Outfitters. There was even a Minor Threat hot sauce. But the scene’s legacy is more than visual. From normcore and Gorpcore to tech bros and clean-living millennials, the contemporary idea that true rebellion is found in a stripped-down and self-controlled aesthetic can be tracked backed to straight edge.

“I think straight edge’s continued appeal lies in its ability to give people a solid set of principles to live their lives by at a time when spiritual and political meaning is lacking,” says Mr Ollie Irwin, a creative account manager in London and longtime hardcore fan. “The tribal appeal and mystique of even football has been replaced by repackaged corporate glitter. At its core, straight edge’s appeal lies in its purity.”

“In a climate where very little control is given to the individual and their own destinies, straight edge allows young people to take back control of their own lives”

Every new generation has taken the basic template of straight edge hardcore and adapted it slightly. “Ideologically, I think we’re witnessing a softening of the previous attitudes and rituals of the straight edge scene,” says Irwin, citing Turnstile, the hardcore punk band from Baltimore, as a contemporary example. “Shows are becoming much more inclusive and less violent and therefore appealing to a much broader audience.”

Chick points to another aspect of Minor Threat’s ethos that has helped it endure. “Partly, it was a reaction against the ‘adult world’,” he says. “A lot of Minor Threat’s lyrical concerns deal with a sense of purity, a sense of simplicity of youth, and drugs are the adult world encroaching upon that of youth, the original sin.”

Whenever this adult world – with its cynicism, compromise and complication – becomes overbearing, young people are going to gravitate back to a scene that rejects all of that, something that clears the ground like a cultural brushfire and allows something new to emerge in its wake.

“In a climate where very little control is given to the individual and their own destinies, straight edge allows young people to take back control of their own lives,” says Irwin. Which is why, 40 years on, that opening salvo from Minor Threat still feels so bracing, looks so good and its central message remains so attractive: turn on, tune in, do not drop out.

The people featured in this story are not associated with and do not endorse MR PORTER or the products shown