THE JOURNAL

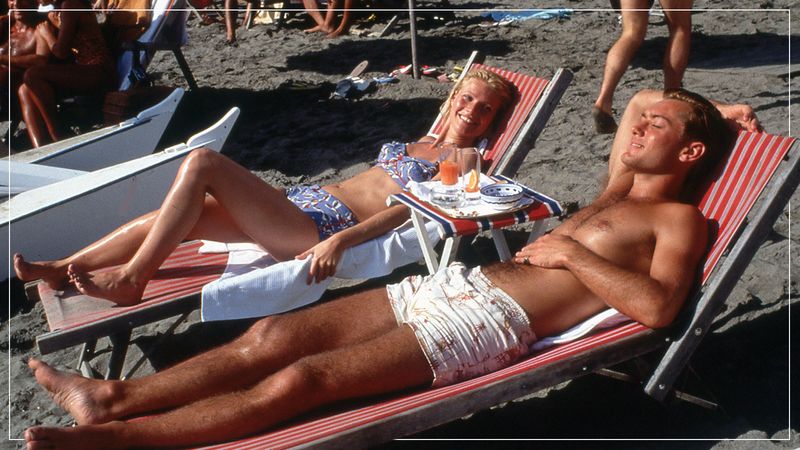

Ms Gwyneth Paltrow and Mr Jude Law in The Talented Mr Ripley, 1999. Photograph by The Neal Peters Collection

From Roman holidays to capers on the Amalfi Coast, introducing the movies that made the country a star.

In the 1950s, fuelled by the postwar “economic miracle”, a second Italian Renaissance exploded in automotive, interior and fashion design and, above all, cinema. And with those came the igniting of the neorealist movement fostered by Mr Benito Mussolini’s Roman studio city, Cinecittà. After the war, Italians craved the new American lifestyle, later encapsulated by Mr Renato Carosone’s song “Tu Vuó Fa’ l’Americano”. But by the late 1950s, everyone else on the planet wanted to be made (and passionately kissed) in Italy.

Rome was once more the centre of the civilised world. Messrs Roberto Rossellini, Luchino Visconti and Vittorio De Sica, the pioneers of neorealism, mingled with the Valentino-clad Hollywood starlets of Roman Holiday, Quo Vadis, Ben-Hur and Cleopatra, and it was all filmed at the Cinecittà’s production facilities. Not only that, but they also reared their own sensual native muses (Mr Marcello Mastroianni, Mr Vittorio Gassman, Ms Sophia Loren, Ms Claudia Cardinale, Ms Gina Lollobrigida) and spawned idiosyncratic prodigies in Messrs Michelangelo Antonioni and Federico Fellini. Meanwhile, the burgeoning paparazzi, a term coined in Mr Fellini’s satire La Dolce Vita, disseminated the pictures.

The new Italy burned with social and moral contradictions: Pucci and the Virgin Mary, Catholicism and the LSD-popping avant-garde, a promised erotic release and Vatican censorship. But these only made for a more creatively fecund land.

By the early 1960s, the world was in the feverish grip of acute Italophilia. A new brand of Italian comedies depicted marriage, divorce and even the afterlife all’Italiana – in inimitable style. Cinema, from then onwards, framed a society both stagnant and changing.

Today, foreign directors still flutter like moths towards Italy’s rose-coloured Mediterranean light and sublime sets, from the volcanic beaches of the Sicilian Islands to the exotic silhouette of Venice’s Basilica di San Marco. After all, Italy does their job for them. Their shots are naturally graced with the omnipresent extras of daily life: the nonna in black lace, the Fiat 500, the Gucci loafer, young lovers on a Vespa. Priests solemnly pacing in and out of frame provide every storyline with a moral and spiritual context – and Italy’s artistic history offers 2,000 years of cultural references.

Oh, and to hell with narrative logic: as Ms Gina Lollobrigida declares in Come September (1961), “I don’t have to make sense! I’m Italian!”

Here are 10 of the most stylish films set in Italy:

01. Stromboli

(1950)

Mr Mario Vitale and Ms Ingrid Bergman in Stromboli, 1949. Photograph by PVDE / Bridgeman Images

The poster alone is enough to make your heart stop. Ms Ingrid Bergman flung in existential despair over the black lava rocks of Stromboli, the Aeolian island’s eponymous volcano vomiting fire into the skyline just behind her. There could be no better metaphor for the obliteration of the cities and values of old Europe post-WWII than the flowing magma, erasing everything on the tiny island. Nor the threat posed by American morals to traditional Italian society, than a foreign (Lithuanian) woman played by Ms Bergman who, having met and married an Aeolian fisherman (Mr Mario Vitale) in a POW camp, finds herself alienated and shunned as a loose woman on a hostile claustrophobic island, abandoned by emigration.

Not that Mr Rossellini did metaphors. Or “style”. But the island’s barren psychological landscape and monochrome palette of volcanic rock and whitewashed geometric houses takes his masterpiece beyond neorealism. Ms Bergman, by then the most famous actress in the world, acted opposite real-life fishermen, including the Brando-esque Mr Vitale – who, in a white tank top and rolled-up fishing trousers, is fit for a Dolce & Gabbana campaign.

Of course, the film is enriched by our knowledge of a second scandalous love story: that of Ms Bergman and Mr Rossellini, both in stifling marriages to others, whose torrid affair on set left the actress pregnant, outcast by Hollywood and denounced in the US Senate as “a powerful influence for evil”.

Get the look

02. La Dolce Vita

(1960)

Mr Marcello Mastroianni and Ms Anouk Aimée in La Dolce Vita, 1960. Photograph by Photofest

Few would deny the sardonic genius of Mr Federico Fellini, a former satirical cartoonist. Recently restored by the Gucci Foundation, La Dolce Vita is an intoxicating melange of glamour and the eroticism of Rome’s demimonde at the turn of the 1960s.

More than 80 locations, including the cupola at St Peter’s that Ms Anita Ekberg’s ascends in couture-cum-priestly attire, were reconstructed by set designer Mr Piero Gherardi at Cinecittà; a secret nod to the artifice of the new milieu where religious miracles are fake, and the fantasy wrapped in the reality of the new housing blocks that encircle Rome.

Marcello Rubini (Mr Marcello Mastroianni) is a socialite tabloid journalist on an endless and aimless nightly “giro” in his 1958 Triumph TR3 through the decaying morality of Rome. In a series of dusk-to-dawn vignettes, he is seduced away from his literary ambitions by sex, urbane banality, cha-cha dancing and ennui.

Rubini is the embodiment of sartorial Italian style in single-breasted black suits, cigarette dangling from his bottom lip, detached behind his nocturnally worn Persol shades.

Get the look

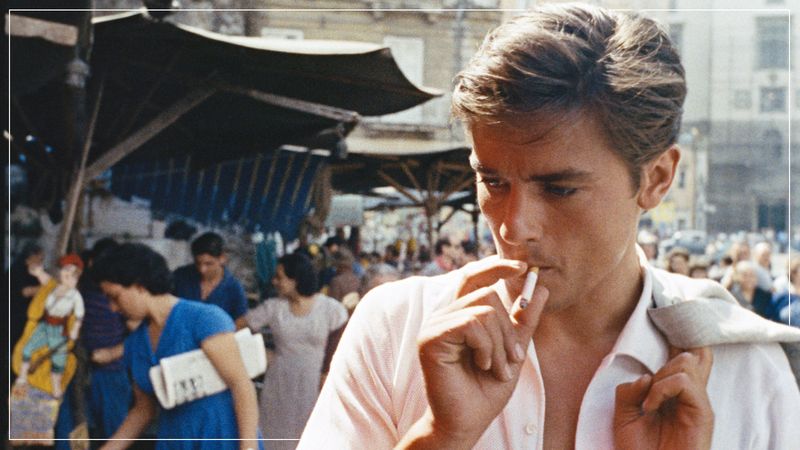

03. Purple Noon

(1960)

Mr Alain Delon in Purple Noon, 1960. Photograph by Capital Pictures

Purple Noon needs only one name as explanation: Mr Alain Delon. The French-Italian film adaptation of Ms Patricia Highsmith’s 1955 crime novel The Talented Mr Ripley shot between Rome, the Amalfi coast and a sailboat, hinges on the then-24-year-old actor’s erotic magnetism, the Mediterranean’s blue reflected in the emptiness of his beautiful psychopath’s eyes. Mr Delon’s Ripley is all Adonic energy, effortlessly charming, but a man without a shadow; just as Mr René Clément directs a Hitchcockian noir in an optimistic palette of yellow, blue and white in the full glare of the midday sun.

Brands take centre stage in this film about appearanc, reality and the acquisition of social class through accoutrements. Devil-may-care playboy Greenleaf (here called Philippe rather than Dickie) is the touchstone of louche jet-set glamour. His white Gucci loafers take on totemic significance when Ripley tries them on and sees the ease with which they fit. After murdering and usurping his rival, Ripley steals his yellow Olivetti Lettera 22 portable typewriter and lounges in Rome like a mannequin in Greenleaf’s blue brocade dressing gown.

Get the look

04. Come September

(1961)

Left: Mr Rock Hudson. Right: Mr Bobby Darin in Come September, 1961. Photograph by Album/akg-images

Hollywood comedy Come September, directed by Mr Robert Mulligan (before To Kill A Mockingbird) was shot in Santa Margherita near Portofino on the Ligurian coast in 1960. But it is a film that still belongs to the 1950s, with its prudish attitude to sex, references to the war, and chaperoned American college girls played by the likes of Ms Sandra Dee. But all this is rocked by the chemistry between the 6ft 5in Mr Rock Hudson and 5ft 5in honeybee-silhouetted Ms Gina Lollobrigida, a quick-witted script (for which you almost forgive the sexism), and a sense that Italy is a land of erotic liberation.

Roberto, an American businessman and playboy, who spends September each year at his marbled villa on the Italian Riviera (played by the Eden Grande Hotel) with his Roman mistress Lisa, flies in early one July, complete with his Rolls-Royce Silver Cloud II Drophead Coupé, to find that his major-domo has turned it into a hotel for summer-breakers. A predictable but fun farce ensues employing split-screens, a drunken parakeet and a rock ’n’ roll performance by Mr Bobby Darin.

Get the look

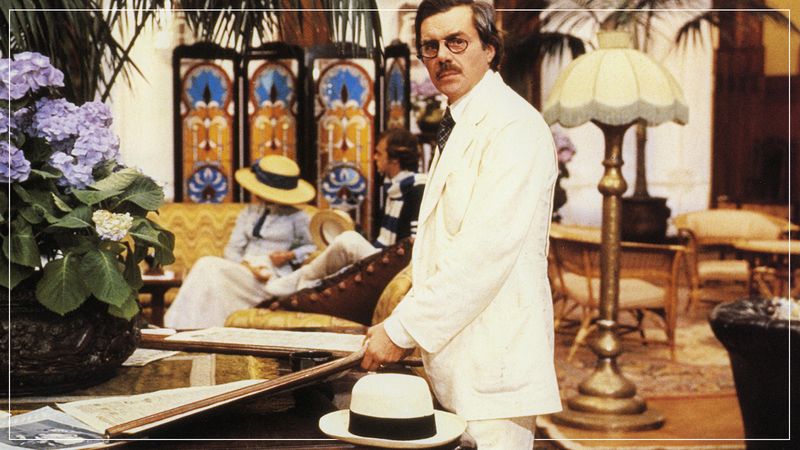

05. Death in Venice

(1971)

Mr Dirk Bogarde in Death in Venice, 1971. Photograph by Alamy

Mr Luchino Visconti’s masterpiece Death In Venice, an adaptation of the Mr Thomas Mann novella, is less a film than a two-hour-long moving painting of remarkable sumptuousness and depth of field set to Mr Gustav Mahler’s Third and Fifth Symphonies. One brothel scene is worthy of Mr Gustav Klimt. Set at Grand Hôtel des Baines on Lido island in Edwardian-era Venice, Mr Visconti turns Mr Mann’s writer Gustav von Aschenbach into an ageing composer (played by Mr Dirk Bogarde) who has suffered an artistic breakdown. While resting on the beaches of Lido, Gustav becomes increasingly obsessed with a beautiful 14-year-old Polish youth, Thaddeus, played by Björn Andrésen. (Mr Mann, like his character Gustav, wrestled with his sexuality, while Mr Visconti was openly homosexual.)

When the punctilious Gustav arrives, he is a man weighed down by heavy trunks, restricted in the proprietous clothes of social convention; by contrast Thaddeus gambols freely on the sands at sunset with his young male companion, both suggestive and innocent, dressed in his marinière swimsuit and a range of tricots rayés. To Gustav, his virginal beauty offers not only a muse of inspiration but redemption: he is the composer’s Michelangelian “David”, and his last chance to be true himself. But Gustav, a man symbolically dying of his unfulfilled desires, is unable to even talk to him.

The sublimeness of Mr Pasquale De Santis’ wide shots, opulent interiors and Mr Piero Tosi’s exquisite costume design (created from the archive of tailor and collector Mr Umberto Tirelli) help distract us from the unbearable pathos of Gustav’s infatuation, which is as doomed as the sinking city. As Venice falls under a plague of Asiatic cholera, Gustav, who refuses to leave Thaddeus, cuts an increasingly sick and ludicrous figure as the indifferent Polish youth turns into his Angel of Death.

Visconti was a Milanese count who mingled with the likes of Mr Giacomo Puccini, Mr Arturo Toscanini and Ms Coco Chanel. As with The Leopard, Death In Venice is an elegy to the break-up of the European aristocracy, its erstwhile elegance and the Grand Tour itself.

Get the look

06. Il Postino

(1994)

Mr Massimo Troisi in Il Positano, 1994. Photograph by Archives du 7e Art/Photo12

Like Mr Giuseppe Tornatore’s Cinema Paradiso, with that sob-inducing soundtrack by Mr Ennio Morricone, Mr Micheal Radford’s Il Postino is a tender look back at traditional island life with the rose-coloured glasses of nostalgia; even the village houses are pink. Set in 1950, the focus here is also on proxy father-son relationships with the wonderful, charismatic Mr Philippe Noiret (Paradiso’s Alfredo) playing Chilean poet and communist Mr Pablo Neruda, who has fled in exile to the island of Procida off the coast of Naples.

When sensitive local Mario Ruoppolo (Mr Massimo Troisi), who refuses his inevitable future as a fisherman, is employed as Mr Neruda’s personal postman, a friendship burgeons between them – the Mr Gregory Peck-ish Mr Troisi, dressed in khaki as if one of the Revolution’s soldiers. Neruda is the catalyst that releases Mario’s poetic nature – like Dante and Mr Gabriele D’Annunzio, he writes metaphors to win the heart of his Beatrice, played by bombshell Ms Maria Grazia Cucinotta – a moment of self-discovery from which he can never turn back. Another layer of pathos was added to the film when Mr Troisi died of a heart attack 12 hours after the shoot wrapped. He was nominated for a posthumous Academy Award.

Get the look

07. The Talented Mr Ripley

(1999)

Ms Gwyneth Paltrow and Mr Jude Law in The Talented Mr Ripley, 1999. Photograph by The Neal Peters Collection

Jazz and homoeroticism are foregrounded in Mr Anthony Minghella’s adaptation of the Ms Highsmith novel, the second after Purple Noon. Mr Jude Law, as the manipulative Dickie Greenleaf, is the focus of eroticism this time, as handsome as he is privileged, all Ivy League meets jet-set cache, cruelty and caprice. Mr Matt Damon wears Ripley’s twisted insecurities on his sleeve, by contrast, winning our alternating repulsion and empathy. He is awkward and clingy, squirming in the skin of his brown corduroy jacket that brands him as a working-class “nobody”, his button-down shirts implying his closeted sexuality.

Ripley desires not only Dickie’s sexual and social power – the white Gucci loafers make another appearance along with knitted polo shirts, pork-pie hats and Sperry Top-Sider CVOs – but to climb quite literally inside his body. The totems of liberation this time are Dickie’s jazz records, the subtext of the memorable scene at Hot Jazz Vesuvio nightclub in which they improvise “Tu Vuò Fa’ L’Americano”. After the murders of Dickie and his sneering college friend Freddie (played with loathsome aplomb by Mr Philip Seymour Hoffman), Ripley dons a black polo neck sweater. Is this a sign of inner turmoil or a cold imitation of human regret in beatnik style?

Get the look

08. Casino Royale

(2006)

Mr Daniel Craig in Casino Royale, 2006. Photograph by Mr Jay Maidment/Album/akg-images

What better place to drown the last vestiges of James Bond’s humanity than a sinking Venetian palazzo on the Grand Canal? The fledging 007 is as doomed as the city (never mind that the scene was shot at Pinewood studios). This Bond reboot striving for grit and realism, the first of Mr Daniel Craig's succession, is loosely based on Mr Ian Fleming’s first Bond novel, published in 1953. Mr Craig’s Bond is a brutish killer in the body of a squaddie: screwed up; impulsive; sexually objectified; at times emasculated, at others maniacal.

Hearts are the film’s motif; the card suit in the poker game against terrorist banker Le Chiffre, Bond’s own cardiac arrest and the betrayal of Vesper Lynd, played with smart froideur by Mr Bela Lugosi’s perfect woman, Ms Eva Green, who removes what is remaining of Bond’s. There is a brief romantic respite in off-duty attire as the pair convalesce post-torture at Villa del Balbianello on Lake Como, the former residence of Mr Luchino Visconti’s grandfather. The other Italian influence here are the suits: designed by costumier Ms Lindy Hemming and handmade at famous Roman tailor Brioni. (Some 25 identical tuxedos were made for the poker scene, to keep the Bond as sartorially impeccable as Mr Marcello Mastroianni throughout his bluffing.)

Get the look

09. The Great Beauty

(2013)

Mr Toni Servillo in The Great Beauty (La Grande Bellezza), 2013. Photograph by Indigo Film/akg-images

After his stylised biopic of one of Italy’s long-serving prime ministers, Mr Giulio Andreotti, played Nosferatu-like by Mr Toni Servillo and nominated for the Jury Prize at Cannes, director Mr Paulo Sorrentino was heralded as the new messiah of Italian cinema. He was an exuberant and fanciful auteur in the mould of Mr Fellini mixed with some Mr Stanley Kubrick, Mr Wes Anderson and Coen brothers thrown in.

Jep Gambardelli is a 65-year-old journalist and eternal socialite (his panama hat, pocket handkerchief and linen blazer recall Sir Cecil Beaton in certain scenes). After turning out a single “fierce” novel in his youth, he has never written a second. The incestuous tittle-tattle and fickle escapism of Rome’s nightlife and circular discussions of Mr Marcel Proust have sucked his resolve and inspiration.

Multiple operatic scenes unfold both dream-like and nightmarish in a world where all is spettacolo. But these, like the majesty of the Colosseum, can no longer thrill the beauty-numbed Jep. Instead, Rome’s bellezza is caught in “the haggard, inconstant splashes of beauty”: novice nuns running in a maze, a giraffe spotlit at night, the “miracle” of a migrating flock of flamingos that perch on his terrace next to the saintly missionary Sister Maria. La Grande Bellezza is both a fantastical love letter to the Rome, its days seemingly numbered, and an elegy to the broken Italian dream.

Get the look

10. A Bigger Splash

(2015)

Ms Tilda Swinton and Mr Ralph Fiennes in A Bigger Splash, 2016. Photograph by Fox Searchlight Pictures/Eyevine

Mr Luca Guadagnino’s film is a loose remake of erotic French thriller La Piscine, which starred Mr Alain Delon and Ms Romy Schneider, and transplanted from 1960s Côte d’Azur to modern day Pantelleria.

Marianne Lane (Ms Tilda Swinton) is a Mr David Bowie-style rock star retreating from the hedonistic music world after an operation on her vocal cords along with her young lover Paul (Mr Matthias Schoenaerts), who is recently out of rehab. The title A Bigger Splash references Mr David Hockney’s painting; the action revolves around the swimming pool and its protagonists are frequently nude. Trouble ensues when Lane’s ex-boyfriend, the pathologically good time-seeking Harry – a music promoter, played by Mr Ralph Fiennes – arrives uninvited with his newly discovered daughter, the Lolita-esque Penelope (Ms Dakota Johnson).

Harry’s needy exhibitionism as he pushes for confrontation is played by Mr Fiennes with outré panache, either naked or clad exclusively in open Charvet shirts. A polka-dot version once worn by French writer Mr Jean Giono was specially recreated. Male competition and ménage-a-quatre impulses bubble beneath the surface – to a soundtrack of the Rolling Stones’ Emotional Rescue – before the final tragic splash. The culprits evade jail. The migrants who’ve also come to the island for shelter do not.