THE JOURNAL

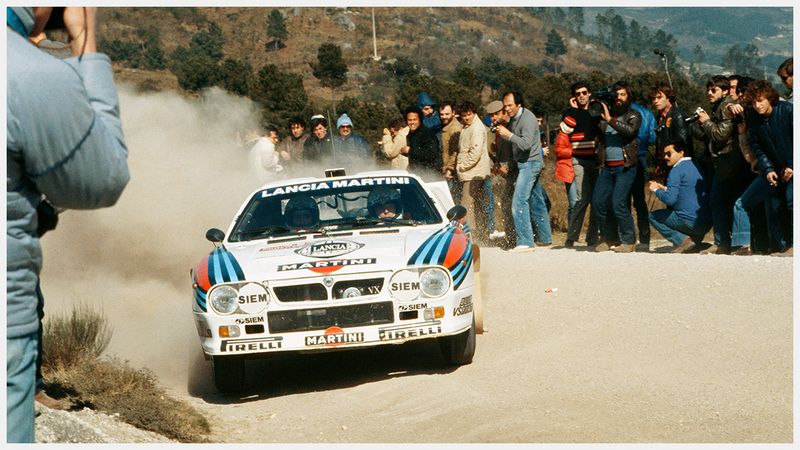

Messrs Attilio Bettega and Sergio Cresto at the World Rally Championship, Corsica, France, 1984 LAT Photographic

The Group B rally fostered some of the quickest and most sophisticated cars ever built, but it was the drivers who paid the ultimate sacrifice.

At the age of just 32, Mr Attilio Bettega was the first to die. The Italian had long ago come to believe he had mastered the art of controlling the very fastest competition cars on capricious, loose surfaces and winding, unpredictable roads.

Born in the university town of Trento, up where Italy and Austria blend, he had no interest in education, or in his family’s hotel business. Mr Bettega wanted to go rallying. He would slip out of town at night and drive the family’s little Fiat 128 as hard as it would go, until negotiating the switchbacks and camber changes, the hairpins and hidden apexes of the Südtirol had become second nature to him.

He entered his first rally in 1972, aged 19, in that very same Fiat. It wasn’t the sort of debut to mark him out instantly as a star. He finished 42nd. But by the following year he was a regional champion, and by 1977 he had won the series Fiat had established to promote the sporting credentials of its new Autobianchi A112, the “Italian Mini”. The win meant an introduction to rallying legend Mr Cesare Fiorio, which in turn meant an introduction to the Lancia team, rallying’s “galácticos”.

Some eight years later Lancia would introduce him to the car that would kill him: the Lancia 037. This was the first of a breed of rally cars that would, over a period of exactly 12 months beginning with Mr Bettega’s accident, bring Formula One levels of performance – as well as unmatched tragedy – to the dusty, icy, muddy kilometres that make up the World Rally Championships. These Group B rally cars would be the most spectacular that motorsport had ever seen, and the most lethal.

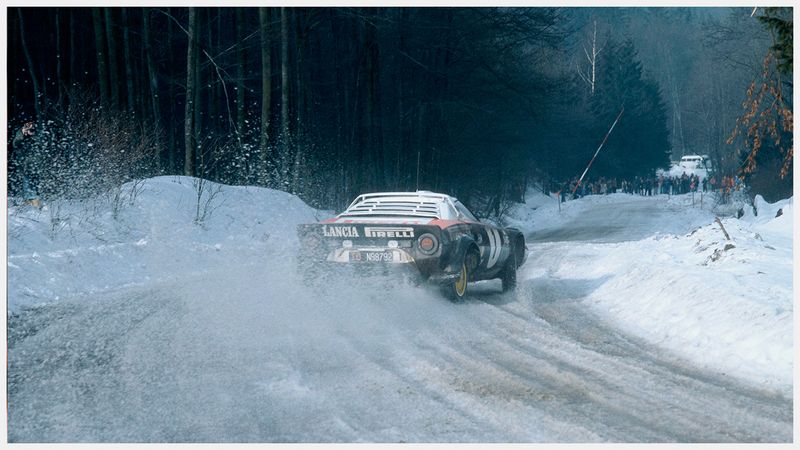

The 037 was in many ways a successor to another Lancia, the Stratos. The Ferrari-engined Stratos dominated world rallying, winning the championship from 1974 through to 1976. It had been a hammer blow from the Italian team, a real supercar in a sport where souped-up family cars had become the norm. Made obsolete by yet another rule, the Stratos left a long shadow. Without it, rallying looked just a little bit ordinary. That’s where the idea for Group B came from.

The Lancia Stratos rally version (1972-1975) Courtesy Lancia

By the early 1980s it was apparent that car manufacturers wanted to go rallying. But they wanted rallying to be sexy again – sexy in a Stratos sort of way. The problem was that it had become too expensive to build supercars capable of taking on snow, mud, gravel and sand. Audi had done just that, introducing four-wheel drive to international rallying in 1981 in the first Quattro, with immediate success. A new formula was required – one that would embrace supercars, but also four-wheel drive.

There were very few rules in Group B and race engineers were given the kind of freedom they dreamt of: the simple challenge of making their cars as fast as possible. Don’t blame them: racers will only ever want the fastest car. Give one a choice of a fast car or a safe car and he’ll always choose the former. And Group B cars were missiles. With a skeletal minimum weight, four-wheel drive and some calculations as to how much power engineers could extract from turbo technology, they were primed weapons just waiting to go off.

And they did just that on 2 May 1985 when Mr Bettega’s 037 left the road on the fourth stage of the Tour de Corse (the Rally of Corsica), hitting a tree. The featherweight car simply crumpled, killing Mr Bettega, but somehow left his co-driver Mr Maurizio Perissinot uninjured. If questions were asked about the suitability of such fast cars to race against the clock on public roads, they were not answered.

Not publicly at least. Lancia, in particular, ignored the warning. It was already working on a new car to replace the rear-drive 037, which by now was getting hammered by newer, four-wheel drive cars from the likes of Peugeot. Two months later, one of those Peugeot T16s, driven by Mr Ari Vatanen left the road in Argentina, tumbling over and over at 120mph. It took Mr Vatanen 18 months to recover from his injuries.

Against ever-increasing odds, Portuguese champion Mr Joaquim Santos escaped with his life when he crashed his Group B car, a mid-engined Ford RS200 on 5 March 1986, less than 10 months after Mr Bettega’s accident, and eight after Mr Vatanen’s.

Mr Santos crashed on the very first stage of the Rally of Portugal. The conditions were as crazy as ever, the crowds even bigger than normal, in spite of – and maybe because of – Messrs Bettega’s and Vatanen’s much-publicised crashes. Group B was spectacular, there was no doubt about that. But with such jaw-dropping speeds came bone-crushing carnage. On the Lagoa Azul leg of the rally, Mr Santos came over a crest and found himself unable to avoid the mass of spectators crowding to watch. On the outside of a bend, his RS200 ploughed into the crowd. Thirty-one were injured. Three were killed.

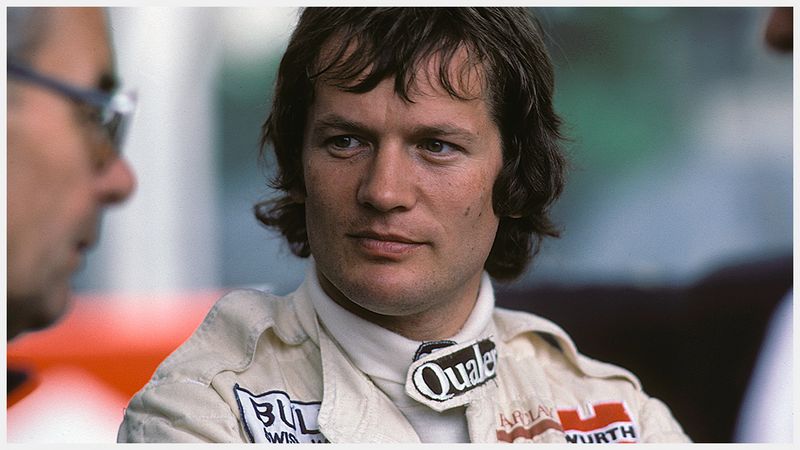

Mr Surer at the Monaco Grand Prix, Monaco, 1983 Rainer W Schlegelmilch/ Getty Images

The destruction didn’t stop there. Just 85 days later, F1 driver Mr Marc Surer crashed another RS200 on the Hessen Rally in Germany. While fighting for the lead, his car went off the road, hitting trees. Mr Surer was thrown clear of the wreck and, although badly injured and severely burned, he survived. Tragically, his co-driver, Mr Michel Wyder, lost his life.

For the 1986 season, Lancia had replaced the beautiful, but by now obsolete, 037 with a new design notionally based, like the all-conquering Peugeot 205 Turbo 16, on a family hatchback. The Lancia Delta S4 was sensationally fast.

By March of that year, doubts finally began to be raised about the speed of development of Group B cars. Around the same time, rumours spread that Mr Bettega’s replacement, Mr Henri Toivonen, had tested an S4 at Estoril, home of the Portuguese Grand Prix, and had set a time that would have put him in the top ten for the F1 race – up there with the Williams, McLaren and Lotus F1 cars.

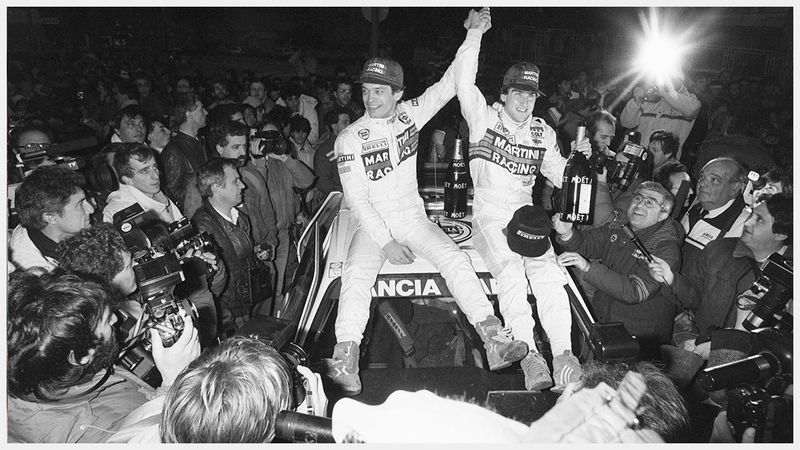

Messrs Toivonen and Cresto at the Monte Carlo Rally, Monaco, 1986 Offside/ L'Equipe

Hailing from Finland, rallying’s spiritual home, and with a former Monte Carlo rally champion for a father, Mr Toivonen had caught Mr Cesare Fiorio’s eye and had been signed first to a limited programme of European events before joining Lancia’s team for a full assault on the World Championship. As a driver, he was the real deal and the Delta S4 was the ultimate Group B car. When the pair took the 1986 Monte Carlo Rally, the traditional season opener, it seemed winning the title would be a formality.

Opting to skip the Safari Rally, Mr Toivonen and the S4 were next seen in action in Corsica, on the same road that had taken Mr Bettega’s life the year before. Dominating the early stages, Mr Toivonen is said to have told journalist Mr Martin Holmes: “The speed is insane. If there is trouble, I’m as good as dead.”

On 3 May 1986, five miles in to the 18th stage, Mr Toivonen’s S4 left the road, plunging into a ravine and catching fire. It burnt with such intensity that only the mangled frame was left by the time fire crews arrived. It was as shocking a sight as anyone involved in rallying had ever seen.

Mr Toivonen and co-driver Mr Sergio Cresto were the last to die. Group B was abandoned the following day.

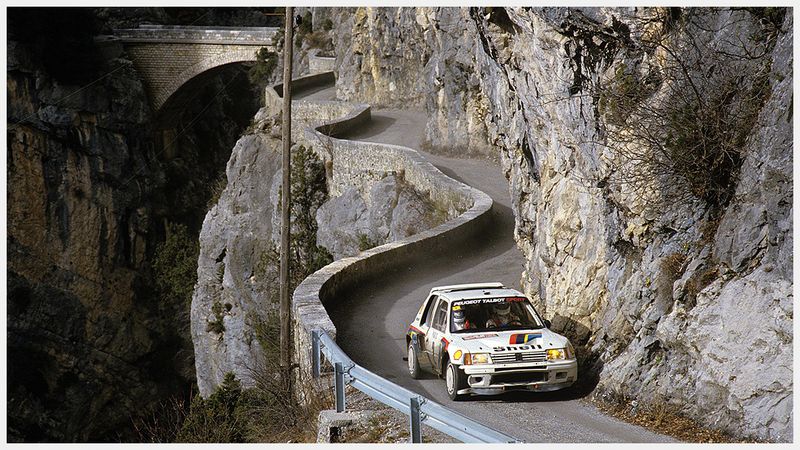

Messrs Vatanen and Terry Harryman in a Peugeot 205 Turbo 16 on the Step Vercors, Monaco, 1985 Offside/ L'Equipe