THE JOURNAL

“Sun & Sea (Marina)” by Mses Rugilė Barzdžiukaitė, Vaiva Grainytė and Lina Lapelytė, at the Pavilion of Lithuania, 2019. Photograph by Mr Andrea Avezzù, courtesy of La Biennale di Venezia

The instantaneous virtual access to the Louvre available on Google Maps is a godsend for the time-poor, but when cruising galleries from the comfort of your own home, it’s easy to get distracted by your Instagram feed. Biennales, the annually alternating art behemoths, immediately focus the mind and the eye, cutting through distraction, because it’s harder for your phone to run interference if you’re sniffing out The Next Big Thing in person.

For the full experience, you ought to go to Venice, to La Biennale di Venezia, the OG biennale, well into middle age as it enters its 58th year. During the preview week in early May, fleets of vaporettos ferry “art types” between showplaces around the old city, locations that reject the white-box tradition of galleries and are curios in themselves.

The energy of the biennale is always up and frenetic. Sometimes, because of the volume of art in Venice, it can feel like a zoetrope speeding past your eyes. Think a principal exhibition of 79 artists and many detached pavilions spread over the verdant Giardini della Biennale and a complex of former shipyards and armories. Your challenge as you enter this maze is to take in all the arresting, breathtaking artistic moments. To help you with that, we’ve rounded up some of our favourites, below.

Lithuania Pavilion, “Sun & Sea (Marina)”

“Sun & Sea (Marina)” by Mses Rugilė Barzdžiukaitė, Vaiva Grainytė and Lina Lapelytė, at the Pavilion of Lithuania, 2019. Photograph by Mr Andrea Avezzù, courtesy of La Biennale di Venezia

A dense queue could be found outside the Lithuanian pavilion. Inside was an indoor beach installation – by three artists including filmmaker and director Ms Rugilė Barzdžiukaitė – which was awarded the Golden Lion prize for best national pavilion. On the shoreline of the beach a group of innocuous vacationers spent a day on the sand. But rather than pasty Brits or a stag party on loungers, the dwellers of the pristine sand were opera singers lamenting the trials and tribulations of modern life. Holidaymakers sang of ecological disaster, piña coladas, the sweatshops that mass-produced their bikinis. A witty take on the vulnerability and the true cost of spending time at the beach.

Mr Sun Yuan and Ms Peng Yu, “Can’t Help Myself”

“Can’t Help Myself”, by Mr Sun Yuan and Ms Peng Su, 2016. Photograph by Mr Francesco Galli, courtesy of La Biennale di Venezia

Art has a false sense of security because there’s only so much damage a stationary watercolour can do, right? Can a marble bust ever genuinely feel threatening? So, any work that’s desperate and foreboding is instantly arresting. Nothing at the fair this year was as ominous as Mr Sun Yuan and Ms Peng Yu’s Guggenheim Museum-commissioned robot, which was manically, mechanically tidying up dark, blood-red liquid. The efficiency of the robotic arm starkly juxtaposed with the latent violence of the pooling blood. It felt like you had stumbled across the bloody aftermath of a vicious incident, with the mesmeric robot cleaning up not only the physical mess, but the incident itself.

Ms Laure Prouvost, “Deep See Blue Surrounding You”

“Deep See Blue Surrounding You/Vois Ce Bleu Profond Te Fondre” by Ms Laure Prouvost, at the Pavilion of France. Photograph by Francesco Galli, courtesy of La Biennale di Venezia

Antwerp-based Ms Laure Prouvost, who won the Turner Prize in 2013, makes you enter the French pavilion through a hole: a void in the centre of Venice, which was initially rumoured to have led all the way to the British pavilion, like the Channel Tunnel. Once inside, the filmic element of the installation is stunning – a sumptuous seascape, a cacophony of psychologically-minded imagery; operatic performance – though the half-truth and rumour beforehand adds to the intrigue. With a burrowing motif infused in all her work (as if the rabbits of Watership Down went to the Slade), Ms Prouvost is a master of the artistic sleight of hand, of misdirection and dissimulation, using a mix of cinema and iPhone footage to build a world that’s almost daring us to believe in it as it slickly undermines itself. We, in turn, question the validity and potency of what we’re seeing with our own eyes. Then you exit – no, you’re ejected – through a mist, blinking in the sunlight and mistrusting the scene in front of you.

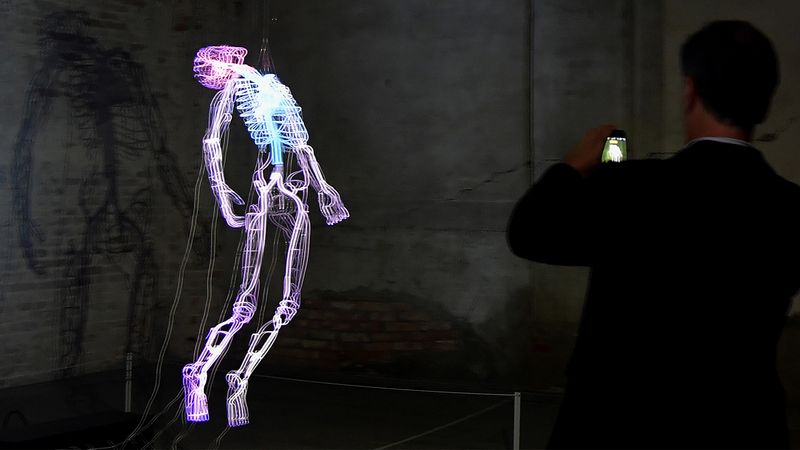

Mr Tavares Strachan, “Robert”

“Robert” by Mr Tavares Strachan. Photograph by Ms Tiziana Fabi/Getty Images

Neon art – strips of acerbic text in bold typefaces – has a tendency to shout at you. Think Mr Bruce Nauman’s sexual trysts. Ms Tracey Emin’s heart shapes. Mr Tavares Strachan, though, has taken the familiar trope to create a haunting portrait: in the darkness, the neon lights trace the circulatory system of a man, suspended in space like a suffocated astronaut without a suit. Fitting then, as the artist pays tribute to Mr Robert Henry Lawrence Jr, the first African-American astronaut. Mr Lawrence Jr never did make it into space as he died in a training accident in 1967 but Mr Strachan’s work casts the oft-forgotten spaceman in a new light.

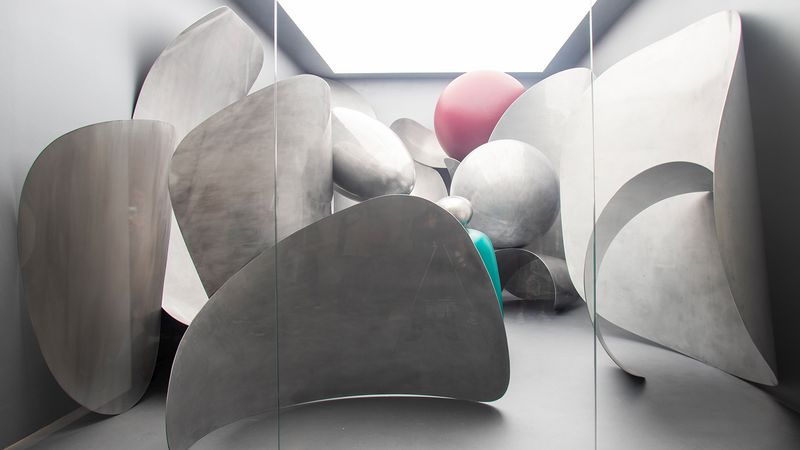

Mr Liu Wei, Microworld

“Microworld” by Mr Liu Wei, 2018. Photograph by Mr Italo Rondinella, courtesy of La Biennale di Venezia

Sometimes art inspires you to be a better person. To live a little differently, or maybe call your mum more. Mr Liu Wei’s “Microworld” makes me want to surround myself with higher-quality goods, from the pen I use to the shoes on my feet. The piece is an exaggerated array of enlarged, polished aluminium plates that make you feel as though you’ve been shrunk down and can see the internal works of an atom on a microscopic slide. The outsized molecules are haunting metal Pringles that your eyes have to travel up to experience, magnified beyond instant recall and recognition. The world is at once smaller and bigger, more detailed and refined. We’re reminded of the inner workings of all things and the intrinsic value of all matter, in its myriad forms.

Ms Tonia Arapovic, “Indecision IV”, featuring Ms Rose McGowan

From left: “Allegory of Indecision I” by Ms Maria Kreyn, 2018, and “Indecision IV”, by Ms Tonia Arapovic, 2018. Photograph courtesy of Heist Gallery

Other times, art can come with a lot of baggage, and the former actress and activist Ms Rose McGowan has brought everything she has with her to the frontline of the #MeToo movement, taking on the Hollywood juggernaut. Ms McGowan’s foray into art at the biennale’s first all-woman exhibition, She Persists, presented by Heist Gallery, challenges prescribed notions of gender constructs. In the nine-minute film installation, directed by Ms Tonia Arapovic, Ms McGowan responds to the movements of dancer Mr James Mulford in an immersive artistic journey with taut, diegetic sound that cuts to the bone.

Mr Cyprien Gaillard, “L’Ange du Foyer”

“L’Ange du foyer (Vierte Fassung)” by Mr Cyprien Gaillard, 2019. Photograph by Mr Francesco Galli, courtesy of La Biennale di Venezia

French artist Mr Cyprien Gaillard’s digital animation appears in the centre of the room as if existing by chance, particles bumping and sticking together until the surreal organism has a beating heart. Despite this feeling of imagination made real, the figure is actually a direct lift from Mr Max Ernst’s 1937 painting of the same name (translating as “The Fireside Angel”). Floating like a whisper of a physical art piece, as light as air, the angel is instantly captivating for its not-quite-there translucence that interrogates the notion of the permanent and real. The piece also questions the idea of ownership in digital times and whether there’s such thing as an artefact if the work is just zeroes and ones.