THE JOURNAL

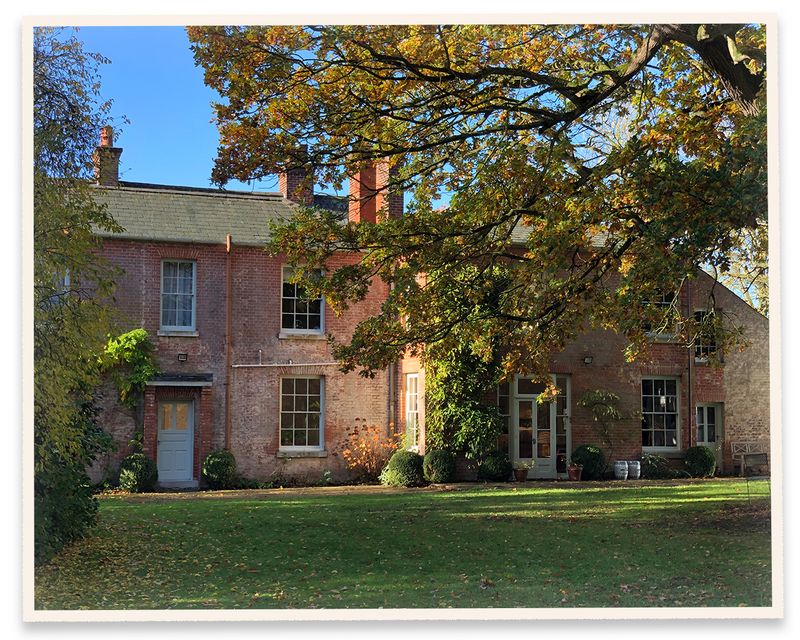

Youngsbury, Hertfordshire. Photograph by Mr Romas Foord

This essay appears in our new book, The MR PORTER Guide To A Better A Day. Proceeds from the sale of the book will go to our Health In Mind fund, which supports men’s mental and physical health initiatives

In 53 years, I’ve lived in 25 different houses – an average of less than two-and-a-half years per home. That’s a lot of decorative schemes and paint charts. An entire warehouse of furniture. To begin with, my mum moved a lot. By the time I turned 18, we’d moved through nine properties. It wasn’t so much that she got bored of where she lived; she got bored of whom she lived with. She cast aside husbands like Henry VIII did his wives: divorced, died, detained, divorced, survived. So packing up my belongings then rearranging them again somewhere new (with someone new) was how I grew up. I learnt from the very best.

My mother was an expert at extracting herself from a place of co-habitation. When she left her fourth husband, only six months into their marriage, I remember standing in their kitchen, watching as she methodically took what was hers from the cupboards and drawers while her broken, sobbing husband looked on in disbelief. She seemed impervious to his distress. “Tony, I can’t remember. Were these wooden spoons yours or mine?” she would ask in a tone that suggested she was doing nothing more dramatic than the morning’s crossword. Eventually, a transient way of life becomes the norm – until it slowly dawns on you that you’re a kind of traveller, just a little more Renault Mégane than Romany.

Once I reached my early twenties, I craved a home of my own. After such a chaotic and unsettling upbringing, with so many different houses and stepfathers – plus eight years of sharing dormitories with 23 other boys at a boarding school – I wanted stability. I longed for somewhere where I could unpack and feel confident enough about to stow the suitcase away; somewhere where I couldn’t hear my mother bickering with a husband; somewhere with a wardrobe that an alcoholic stepfather couldn’t hide his empty bottles of booze in; somewhere where I could display my incongruous collection of Ms Beatrix Potter china figurines and back issues of The Face. So when I got my first job, fresh out of university and with a salary of £11,000 per annum, I immediately started hunting for a flat of my own.

It quickly became clear, however, that I was being a tad ambitious. With my meagre pay packet and mortgage interest rates in 1990 at about 15 per cent, nothing was within reach. I reluctantly teamed up with an old schoolfriend, Stephane, to purchase somewhere together. Before too long, we found a light and airy, if somewhat shabby, flat in north London for £79,000. We put down a deposit of £1,000 each, miraculously got a mortgage agreed and it was ours. Aged 23, we were homeowners. It was only then, days after moving in, that I realised that years of domestic trauma had turned me into a decor dictator. Poor Stephane was barely allowed any say in how the flat would look. I allowed him to choose the colour of his bedroom walls and to be in charge of the kitchen, which I would barely use.

“I don’t think I truly want to find perfection... I like the distraction of buying stuff, creating new Pinterest boards, dreaming up a fresh stage set for the next chapter of my life”

I spent the next few months bidding for furniture and paintings at the Criterion auction house on Essex Road, painted the sitting room and hallway Imperial Chinese Yellow and went for a Moroccan theme in my bedroom. Each time Stephane tried to introduce something of his own to our shared living space, I would promptly dispatch it to his bedroom. We reached an impasse with a ginormous rubber plant that he insisted should live in the sitting room. I hated it. Its 1970s vibe did not go with my cut-price Sibyl Colefax & John Fowler scheme. Each morning, after Stephane left for work, I would pour copious amounts of household bleach into the plant pot in an attempt to massacre it. It stubbornly refused to die. And its continued existence saddened me on a daily basis.

A few months later, in another effort at conjuring the domestic bliss that had eluded me as a child, I bought a kitten, a sweet, fluffy Persian tabby. Stephane tolerated the litter tray halfway up the staircase, forgave the playful mayhem the kitten caused when left alone during the day and didn’t mind playing with it each night while I was out at various nightclubs. What Stephane didn’t realise was that each day he was merely nurturing his tree’s future assassin. Well, assassin’s aide. After a few weeks, when the kitten was a fraction bigger, I hatched an evil but, frankly, genius plan. I waited for Stephane to depart for work, then pushed the rubber plant over, snapped the trunk in two and left it for dead. On returning home that evening, I feigned surprise as Stephane told me of the grotty crime scene that had greeted him. “Oh no,” I sympathised. “That pesky kitten. I can’t believe he did that.” Stephane obviously couldn’t quite believe it either. “I don’t understand how its falling onto the carpet would have caused the trunk to snap,” he puzzled.

Some 18 months later, I moved out of our flat to live with my girlfriend. Once we were married, I sold my half of the flat to Stephane. Due to a recession, and the fact I had minimal equity, all I got for it was £800. I spent the entire sum on a Prada leather jacket. Stephane bought lots of new plants.

Moving in with a partner is another rite of passage in one’s interiors life. You have to find a style that you both like and learn to compromise. You need to kindle passions for decorative schemes that you can readily share and afford and, within time – in our case, a scant six months – adapt to take into consideration the needs of a baby. Sisal becomes impractical, coffee table tableaux unwise and storage for mounds of ugly plastic toys a top priority. For this next stage, I cast aside my aristocrat-falls-on-hard-times approach for something clean and contemporary. My mother-in-law was married to Lord Norman Foster and so we were greatly influenced by the amazing, triple-height, riverside penthouse that they lived in by Albert Bridge in Battersea. We tried to apply his steel-and-glass aesthetic to our diminutive three-bedroom Victorian terrace nearby.

Youngsbury, Hertfordshire. Photograph courtesy of Mr Jeremy Langmead

During your twenties and thirties, your approach to interiors is heavily guided by budget (hello, Ikea), your peer group and a plethora of TV shows and design magazines (or now websites such as the The Modern House), as well as a gritty determination not to have a home that resembles your parents’. You’re still establishing your adult credentials, learning who you are and what you like, and what you need from a residence can quickly change with relationship status, parenthood and even jobs.

When, in my late thirties, I became the editor of Wallpaper* magazine, a publication that championed Italian furniture, Scandinavian minimalism and Brazilian architecture, my quirky Hackney house with its bright pink walls and perky mishmash of furniture and paintings no longer seemed appropriate. Since I was now divorced and my sons lived with their mum, I sold up and predictably bought a loft in Shoreditch. It was huge and open plan. You could cycle around the living space, buy giant pieces of furniture that looked like they’d been crafted by Nasa and stare out of curtain-free windows onto the grisly sounding hen parties spilling out into the streets below.

At first, there was something freeing about starting all over again, not having any clutter and living directly above one of the capital’s most fashionable restaurants. But after a year, I began to realise that it wasn’t really me. I missed looking at the lovely things I’d collected over the years. I tired of gazing at office blocks rather than at my beloved collection of paintings by unfashionable Bloomsbury artists. I was now 40 – that joyous stage when you truly care much less about what everyone else thinks. With age comes freedom.

Ashbocking, Suffolk. Photograph courtesy of Mr Jeremy Langmead

Off I went, once again. And out went the noisy loft with its soulless, fashionable furniture. Instead, I bought a charming garden flat on a magical square in Primrose Hill. It hadn’t been touched in decades. There were dead animals behind the radiators, 20-year-old meals adhered to the kitchen surfaces and an off-putting smell of cabbage emanating from the drains. None of that put me off. This time, the style I went for was bisexual Bloomsbury artist meets 1970s playboy. I bought first editions of all nine of Mr David Hicks’s interiors books – his aesthetic was hugely influential in the 1960s and 1970s, when he was the decorator of choice for everyone from Prince Charles to Ms Jackie Kennedy – and tried to imitate his knack for mixing old and new, colour and pattern. There were dark, ornate wallpapers, brown Carrera marbles, low lighting and objects and paintings galore. I realised the look had worked when one night a famous young actor asked if he could use my flat as a shag pad while I was away travelling. (The answer was no.)

Another few years, another marriage – another move. We needed space, fresh air, a bigger garden, no neighbours… More rooms to decorate. As your life becomes more hectic, your work more time-consuming and your time left on this earth palpably shorter, a sense of escape and tranquility becomes more desirable. You crave a nest, a refuge where no one asks anything of you.

London. Photograph courtesy of Mr Jeremy Langmead

Still, over the nine years that I worked at MR PORTER, I moved four times.

My shrink and I often discuss why I’m forever looking for the next place, restlessly seeking perfection. With each new home, I’m intent on creating a perfect new world, a domestic utopia. When it (inevitably) doesn’t quite make the grade, I pack up and try another. Ultimately, I don’t think I truly want to find perfection. It’s the journey I enjoy. I like the distraction of buying stuff, creating new Pinterest boards, dreaming up a fresh stage set for the next chapter of my life. Despite fighting it since childhood, I’m more like my mum than I care to admit. I toss aside houses as recklessly as she did husbands. I’ve even noticed that I’ve started to appreciate certain items of furniture she used to like in her homes, too. It all comes full circle.

So where am I now? Mr Charles and Ms Ray Eames, two of the most influential furniture designers of the 20th century, had it right. Despite their strong design aesthetic, they believed that your home should tell your story, that shelves should host an eclectic collection of objects that you’ve accrued over the years. Your past, like the wrinkles around your eyes, should be embraced and not erased. We are all our own curators and our homes should tell the stories we want to tell, perhaps even some that we don’t. You should be able to cast your eyes around you and be reminded of a life well travelled and, ideally, one well lived. Fortunately, now that we’ve all become more design savvy, thanks in large part to the internet, we are confident enough to be more eclectic in our tastes. Ikea now sells chintz, for example; Wallpaper* magazine now celebrates maximalism as well as minimalism.

Most important of all is to accept that your home has to function for the life you lead now. You can’t really design one for the life you want to lead next. What you need and want changes all the time. And that’s as it should be.

Low Blakebank Farm, Cumbria. Photograph courtesy of Mr Jeremy Langmead

One of my sons, who recently graduated from university, has just moved into a flat-share in an urban part of east London. He proudly showed me around. His bedroom was small and cramped and overlooked a supermarket car park.

“It really is perfect, Dad,” he said. “I wake up in bed and all I can see is my collection of sneakers.”

“It’s a shame about the view,” I said, looking out of the window at the giant branch of Tesco.

“What do you mean?” he replied. “I can get up, look out and all I see is where to buy my cigarettes. Doesn’t get better than that.”

Meanwhile, I’ve moved to Cumbria in the north of England. I’ve bought a small farmhouse in the land of lakes, mountains and Wordsworth. The house is surrounded by wild flowers with far-reaching views across green, fertile valleys. The Lake District is where Ms Beatrix Potter wrote her books. My china figurines of Mrs Tiggy-Winkle and Jemima Puddle-Duck have finally come home.